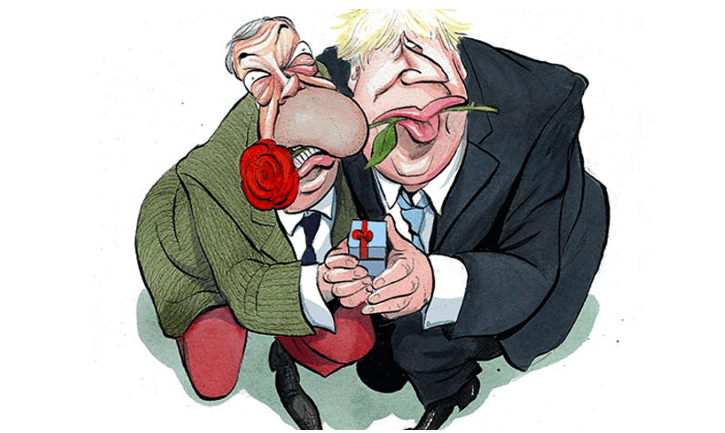

A few weeks ago, Nigel Farage enjoyed a get together with a very senior Conservative party figure. Brexit was, naturally, at the heart of the conversation. As he departed from the convivial rendezvous he delivered a line that lowered the temperature in the room and is likely to concentrate Tory minds: ‘If you screw it up again I will come back and kill you.’

So far there is little sign of Boris Johnson’s administration going soft on post-Brexit negotiations. While any final future relationship deal is bound to contain compromises that could be presented as a betrayal to an ultimate Brexit purist, it will only blow up in the Government’s face if the general body of Brexit supporters come to think of it that way. And there is every indication that the high-ups of the Vote Leave operation who run Downing Street understand that and won’t go there.

But Tory wariness of Farage persists and is understandable. After all, this is the man who has built a political brand that has haunted the party’s every waking hour not once, but twice. The first time round, David Cameron conceded an EU referendum in large part because, as he told Nick Clegg at the time, (reported in the memoirs of David Laws): ‘I’ve got UKIP breathing down my neck.’

The second time, it was Farage’s pop-up Brexit party that effectively ended Theresa May’s premiership by winning the European elections and collapsing the Tories down to a derisory nine per cent vote share. It may have had a lifespan of a single year, but what a year it was.

So could there be a third dose of Farage on the horizon? And given growing discontent among Tory-inclined voters about various issues, why hasn’t it happened yet?

Well, yes there could be. Those close to the former Ukip leader say he has noticed that a big chunk of the 2019 Tory vote – perhaps up to a third – has ‘worked loose’ already on three separate issues: an apparent failure to stand up for British history and culture; opposition among libertarian-inclined people to lockdown measures and the continuing chaotic immigration system.

Of these, he thinks the third has the most potential traction and has made exposing it a major part of his political and social media activity over the summer and autumn. The other two issues are regarded as potentially useful supporting pillars for an alternative offer from the Right but less likely to effect an outright change in the way people vote.

So all those Tory MPs scoffing behind their hands at Priti Patel’s efforts to move the asylum processing system offshore and to otherwise ‘Australianise’ UK immigration procedures should understand that if she fails then that would be the most likely thing to bring the long shadow of Farage back into their lives.

But there are several things holding him back. First, he has noticed that he can have an impact on the Government just by looking as if he is ready to crank things back up – as with the remark reported above and also when he threatened potential Tory rebels on the Internal Market bill with local Brexit party campaigns against them. From his point of view, if he can get results just by ‘clearing his throat’ does he really need to go through the slog of building a party to national prominence for the third time – with the likely denouement of dragging the Tories onto his ground but his party failing to win parliamentary seats?

Another factor is his other interests, with the prospect of TV channels potentially looking for big name presenters who can bring guaranteed followings with them and the US presidential election building to a chaotic climax.

Friends say the only thing likely to force his hand in the short-term is if another rival new party from the Right gets traction and starts performing well in by-elections and the like. But his circle is sceptical that any of the wannabe new entrants – including Laurence Fox – have the necessary skill-set or reach to do that.

A quarter of a century as a campaigning underdog have led him to understand the daunting range of hurdles the British system places in the way of new entrants and what it takes to surmount them. As he told one confidant about the looming European elections in 2019: ‘I know what to do. I can make people achieve unreasonable things.’

Recent political history tells us that there are around four million voters highly susceptible to his appeal. At the 2015 general election, a substantial number of them defected to Ukip from Labour, causing the likes of Ed Balls to lose an early smattering of ‘Red Wall’ seats. For many such voters, Ukip proved a gateway to voting Tory in the 2019 general election.

The Farage appeal to Labour voters has dwindled – most of those who agreed with his outlook are no longer Labour voters anyway. Instead, they are clustered in the Conservative pile, along with a stack of traditional shire Tories who regard Desmond Swayne as their current pin-up and may also regard Nigel as Desmond by other means.

Were he to re-enter the fray even as the ‘Mr Ten Per Cent’ of British politics, Nigel Farage could completely transform the scene to the massive detriment of the Conservative party.

So he watches and he waits, knowing all the time that a Tory failure to deliver on Brexit or immigration will let him back in the game. A memo to the Tories about how to fend him off could be written in two words: Don’t fail.

Comments