Having spent too much of my life at both poles (writing, not sledge-pulling), I know the spells those places cast. Michael Bravo promises to reveal something of that enigma, claiming at the outset of his book: ‘I will treat the mysterious power and allure of the North Pole in a way you will not have seen before.’

The volume is one of an interesting series on the cultural history of natural phenomena, that includes a title on Fire, and another on Swamp. Bravo structures his book around the struggle of navigators and philosophers to make sense of the strange powers of the North Pole, beginning with the ancients of Greece, Egypt, India and Persia. For many centuries nobody knew that the Antarctic is land surrounded by water and the Arctic is water surrounded by land (many folk still don’t grasp this). Bravo diligently tracks discoveries, notably that of magnetism, drawing in the ideas and mythologies of Inuit peoples indigenous to the region. He reveals the planet yielding its secrets. Individuals emerge in the process as he conjures their achievements and theories. William Gilbert, for example, Elizabeth I’s doctor, was a brilliant inventor in the field of magnetism (‘Gilbert was a radical and strident anti-Aristotelian in his practice of both medicine and natural philosophy’).

Bravo draws on primary and secondary sources, many not published before. ‘Since early modern times,’ he writes, ‘the pole had always been about hidden forces, celestial harmonies, viewing the earth from the heavens or transformations deep inside the earth’s interior.’ He is most interested in the role the North Pole has played in the public imagination down the ages, especially in the history of geographical perception and the pole’s place in ‘the cosmographical relationship between the heavens and earth’, notably how that perception shifted, for example in the period of expanding European global empires.

Utopians and fantasists get a look in, as does Madame Blavatsky, who seems to crop up everywhere — a shame, as all her ideas were terrible. Characteristically of North Pole: Nature and Culture, the Blavatskian thesis is clumsily expressed:

For Madame Blavatsky, the continent Hyperborea occupied a different immaterial and less literal metaphysical space and therefore couldn’t be grasped or claimed by imperial conquest.

A few pages cover fiction writers, such as Mary Shelley and A. A. Milne (surely you remember Christopher Robin leading an ‘expotition’ to the North Pole?).

‘The Multiplication of Poles’ is a key chapter, explaining the difference between, for example, the geographic North Pole and the Magnetic Pole. Bravo stresses the oddness of 90 degrees north. ‘Spatially when standing at the North Pole every direction faces south,’ he says. When I was at the South Pole a jovial Muslim astrophysicist used to make a great joke about which way to face while praying.

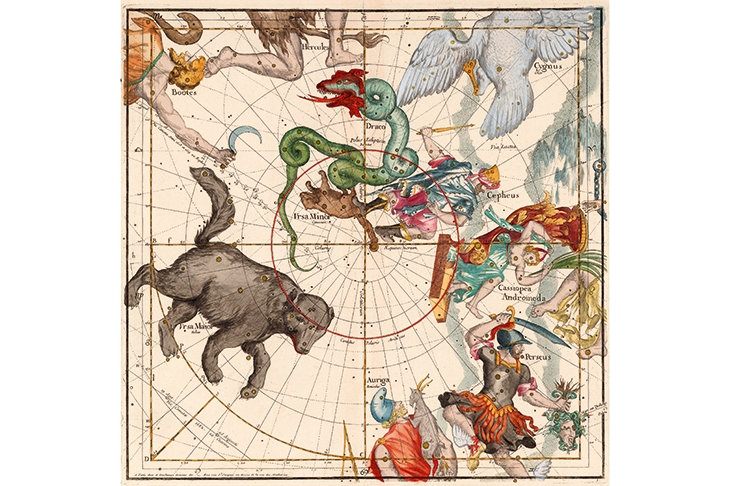

The strength of this short book lies in its illustrations — more than 100 of them, brilliantly selected and reproduced. The whole volume is printed on glossy paper. The pictures range from sumptuous full-colour portraits to woodcuts, drawings of little wooden ships in the pincers of a floe, and early maps. It’s hard to pick favourites, but I loved especially the drawing of Ursa Minor from Al-Sufi’s 11th-century Book of the Fixed Stars, and George Cruikshank’s superb 1819 colour etching ‘Landing the Treasure, or Results of the Polar Expedition!!!’, which parodies expeditioners marching home with a retinue including Jack Frost and a polar bear. Later on there are photographs, including a gorgeous one of Fridtjof Nansen, who refined the art of polar skiing while drifting in the Fram. Nansen is the greatest polar explorer ever to have lived.

The prose style, however, is as creaky as a calving berg. One learns that: ‘Across most societies, the ability to align and organise oneself spatially is what binds people and cultures to the night sky.’ Similarly:

Any imperial expression of a desire for universal earthly authority requires an act of sovereignty that breaks a taboo in order to become the law-maker rather than the law-follower.

Bravo is a senior lecturer at Cambridge University, and one detects all too often in these pages the dead hand of the academic.

The shoe-eating explorers of yore sail in and out of the book, but Bravo eschews the colourful anecdote, ignoring the narrative’s gasping need for specificity. For example, he mentions Ivan Papanin, a Russian Cold War warrior on the coldest front, but he does not tell us that while Papanin and his colleagues were drifting on a floe they had a fixed bicycle to power the generator which in turn powered the wireless, enabling the men to listen to eight-hour sessions of the Thirty-Seventh Party Congress. Pedalling was a popular job because it was the only occasion during which those benighted individuals were allowed to smoke.

Comments