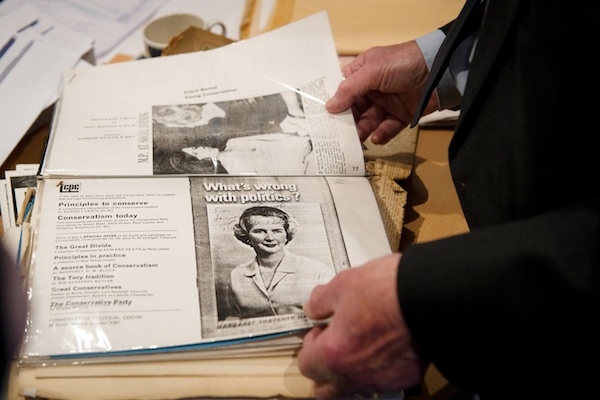

Any Tories who might be asking ‘What Would Thatcher Do?’ about some of the political rows bubbling away today would surely wonder what her response to the current benefits debate might be. She kept well away from welfare reform, but she did have strong views on the role of government in helping people get on. Her notorious Woman’s Own interview provided us with the greatest insight, and in much greater detail than the ‘there’s no such thing as society’ line that everyone can quote. Here’s a longer extract from the transcript (which you can read in full on the Margaret Thatcher Foundation website):

‘I think we have gone through a period when too many children and people have been given to understand “I have a problem, it is the Government’s job to cope with it!” or “I have a problem, I will go and get a grant to cope with it!” “I am homeless, the Government must house me!” and so they are casting their problems on society and who is society? There is no such thing! There are individual men and women and there are families and no government can do anything except through people and people look to themselves first.’

Her words, still forceful and still as divisive as that standalone ‘no such thing’ quote, do highlight one element missing from the welfare reform debate of the past fortnight. The focus has been either on cuts aimed at driving down welfare spending, or on Iain Duncan Smith’s Universal Credit, aimed at making work pay. But there has been little discussion of the importance of supply-side reforms which would drive the benefits bill down for the long-term. The focus of anti-poverty campaigners is very often on cash transfers to alleviate market failure of one form or another, rather than the importance of addressing the source of that pressure on low-income families. And it has been the same for politicians too.

George Osborne’s decision to link Mick Philpott to the case for welfare reform was, as Fraser explained at the weekend, deeply disappointing. The Chancellor clearly wants to show hardworking families that he’s on their side, but using six dead children was a horrible, crude way of doing this. He and other ministers could make a powerful case to ‘hardworking families’ that the time has come for taxpayers to stop paying for idleness: the idleness of politicians, not benefit claimants. The housing benefit bill has been set on an unaffordable trajectory, not because people have been getting lazier, but because for years politicians have been too lazy to ensure enough homes are built.

There is a strong small-state case to be made for supply-side reforms like liberalisation of planning laws. Why should taxpayers subsidise governments to oversee restrictive planning systems and to lack political will to build enough affordable homes? Nimbys may dislike the view from their window changing when a new housing development appears, but there are many, many more fiscal nimbys who would hate the idea of a government using their money to paper over the cracks with benefit payments rather than hacking away at the cost of living.

Osborne is often hailed as a great political strategist. He loves playing games with the Opposition. And he could do so with Labour: they failed to build enough roofs when the sun was shining. There was not one year of Labour’s 13 in government when the number of new homes reached the 250,000 that economists estimate the country needs. In those days of easy credit, 219,070 in 2006/07 was the closest Labour got. Jon Cruddas, now the party’s policy review chief, argued in the same year that his own government’s failure to build sufficient affordable housing was pushing demand to ‘crisis’ point.

Instead of creating a functioning housing market, the Labour government relied increasingly on housing benefit to top up unaffordable rents with the result that the bill now stands at £23bn. House prices have outstripped wages and inflation. Families continue to hang on by their fingertips, reliant on welfare payments rather than being able to make their own way without the state. Government has got in the way of people affording to live their own lives.

The effect of pressure on the public finances and of continuing undersupply of housing is like the effect of pressure on both sides of the human digestive tract: it causes someone to vomit. The system can’t cope with both for ever, and will at some point go into spasm, which it has done. Labour had the opportunity to remove that pressure by focusing on the supply-side problems in the housing market before the housing benefit bill reached such a height that it had to be cut. The party didn’t take that opportunity and only made some half-hearted noises about the need to cut the bill in late 2009. This crisis wasn’t inevitable.

What would Thatcher do? Chances are she wouldn’t be quite so worried about upsetting the National Trust as many Tories are today. But her Woman’s Own interview is clear that she believed the state should let people get on with their own lives, not interfere like an annoying mother-in-law at every stage. Failing to build enough homes forces government to get involved in just that way, creating a problem that it then has to cope with through cash transfers. The government has had to do what Labour knew it would have to do too: it is cutting the housing benefit bill. But it could also be bold about doing what it really, really needs to do: creating a planning system that allows enough homes to be built each year for it to get out of people’s lives and leave them to thrive in what Thatcher called the ‘living tapestry’.

P.S. A forceful critique of the current poverty debate, for those who are really interested, comes from the IEA’s excellent paper by Kristian Niemietz, ‘Redefining the Poverty Debate’. It doesn’t make particularly comfortable reading, and rejects the current obsession with cash transfers for a focus on driving down the cost of living.

Comments