I’m glad Norman Scott can say he has ‘always had the ability to laugh at the absurdity’ of his existence because, as detailed here in a long-awaited memoir, I too couldn’t stop shrieking, he is so tragic. When he came home unexpectedly as a youngster, for example, and witnessed his mother having sex in the lounge with a telephone engineer, he was so shocked he dropped his tortoise. ‘The terrible guilt over my tortoise stayed with me,’ he writes – maybe until just the other day. Scott is now 82.

He’ll always be remembered of course for the Jeremy Thorpe trial, when the judge, Mr Justice Cantley, called him a fraud, a sponger, a whiner and a parasite; and Scott’s haplessness is truly in a class of its own. I know he was played on television tenderly and sensitively by Ben Whishaw, but the personality in An Accidental Icon is more Jim Dale when, in one of the Carry Ons, he zoomed about tethered to a floor-polisher or clattered down steps on an iron bed frame. I lost count of the times Scott wakes up ‘strapped to an iron bed’, whether in psychiatric wards or when romantic assignations go awry: ‘I couldn’t move. My wrists and ankles were tied.’

A commingling of horror and farce is never distant. An unhappy childhood sets it all in motion: desertion, insecurity, violence. Scott had a stepfather who ‘got hold of Mummy by her hair and threw her down the stairs’. The nuns at his convent school were bullies. Friends were few. He had a stammer and curvature of the spine. He wet the bed; and any adult he met fiddled with his flies. ‘The sense of something unkind and unpleasant about to happen was always present.’

Thorpe’s acquittal of conspiracy to murder was the greatest miscarriage of justice of modern times

His mother was no support. She wanted to have him taken into care: ‘I can’t control him. He’s just difficult.’ Scott’s salvation was horses: ‘They didn’t see me as weak or vulnerable or someone they could manipulate.’ No, they simply threw him off, bucking like mad in ‘a nightmare of flailing hooves, sky, brown earth, splinters of wood’, leaving him concussed and with shattered vertebrae.

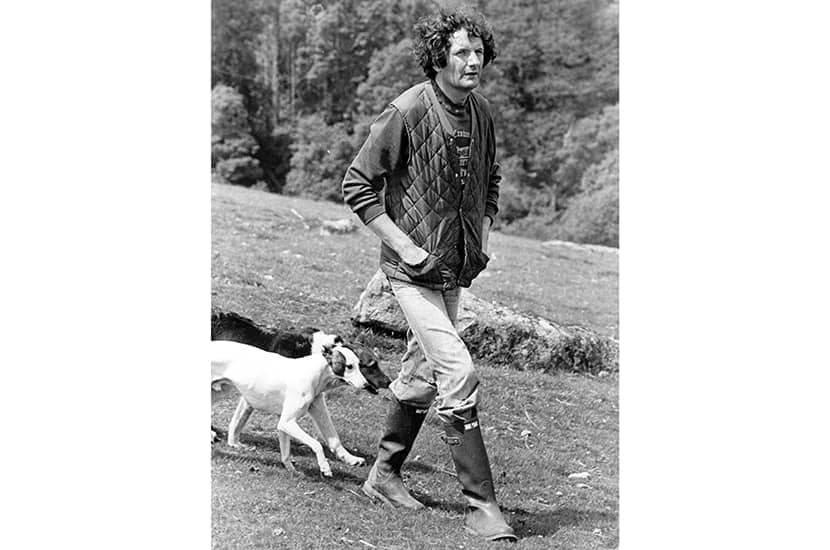

Scott is undoubtedly brave, mastering these vigorous creatures. He has spent his professional life in the equestrian world of dressage, three-day eventing, jumping and racing, and was employed as a stable lad and groom by many a ghastly old snob, bore, lunatic, sadist, bankrupt or associate of Princess Anne. One morning on his way to work he fell off his scooter, breaking limbs, which caused him to reflect: ‘I had found myself gripped by a bleak premonition that nothing would ever go right for me.’ Nor did it. The doctors put him on high doses of tranquillisers and antidepressants and he found it impossible to sustain relationships.

In one typical sequence he moves in with someone in the Cotswolds. Their mental anxieties clash and soon everyone is ‘placed in a psychiatric clinic’. They escape, rent a flat in Oxford and ‘within a week Jane had slashed her wrists’; the other person, Brian, gets drunk and hurls a pass (‘he was a big, strong man and at first I was very scared of him’), before somebody else switches on all the gas taps. Scott throws a chair through a window and goes for a walk with Brian, who tries to drown them both in the canal. Later on the gas trick is tried again, and Brian was ‘standing over me, holding a knife’.

This sort of caper happens every day. Friends vanish and turn up in Australia or commit suicide in Wales. Scott is always getting the wrong train, or finding himself stranded in the middle of nowhere, his luggage lost. Businesses close down, leaving him in the lurch. Helicopters buzz his bungalow. Pranksters phone up pretending to be Michael Heseltine. Doctors he trusts are struck off. One minute he is a male model in London, sharing premises with Margot Fonteyn (‘she spoke about her involvement in the Panamanian revolution’), the next he is in Dublin, being intimate with a member of the Dáil and Elizabeth Taylor’s secretary – Taylor and Richard Burton having ‘returned to the yacht to be with their pet dogs’. If this is meant to be 1964, the only time the Burtons were in Ireland, then it’s worth mentioning they didn’t acquire a yacht until May 1967.

I relished this book’s celebrity cameos. In a Dulwich flat filled with ‘flamboyant and extrovert’ sorts, Lord Snowdon is glimpsed. Scott’s mother’s best friend was Dorothy Squires. When Scott was (very briefly) married in 1969, he spent his honeymoon in a cottage owned by Terry-Thomas and there were elderly Czech refugees hiding in the bathroom. Scott says he slept with Francis Bacon, who snored, and next morning said: ‘You’re not my usual type.’ Scott’s favourite West Country pub was run by the son of Fanny Cradock.

Thorpe, who first encountered Scott at one of those grisly stables, was intrigued enough by the sound of this picaresque existence to give him his telephone number – and Scott, who during one low ebb ‘ended up sleeping in the men’s lavatories in Barnstable’, was naive enough to believe that Thorpe could rescue him. He appeared at the House of Commons, where the MP ‘put his arm round me in a warm friendly gesture’. Thorpe took Scott home to meet his mother, a grim old trout called Ursula, who knew the score. The abuse began immediately. Scott relates how ‘he held me down with great force as he thrust violently into my body. It hurt so much I was gasping with pain.’ Thorpe took full advantage of a vulnerable, medicated person. ‘I was forced,’ says Scott, ‘into non-consensual, illegal, agonising sex by a man in a position of considerable power and influence… I was just a vessel for his pleasure.’ One interesting fact emerges: Thorpe had nodules on his balls.

Scott had no redress. No one was interested in his complaints. ‘I just don’t believe you,’ said David Steel. ‘I don’t believe this could have happened.’ Evidence went missing. Briefcases containing letters were stolen. The authorities treated Scott as a blackmailer. Several times he was roughed up by the police or security services. ‘If you don’t cooperate, I have the power to lock you away and you won’t see the light of day for 14 years,’ he was told, before having his head banged against a cell wall. Thorpe kept Scott’s National Insurance cards, in an attempt to control him, and Peter Bessell, the Liberal member for Bodmin, paid Scott a weekly retainer to ensure his silence. Thorpe, meantime, seduced sailors at Dan Farson’s pub on the Isle of Dogs. He was thoroughly homosexual, despite two marriages. Being with a woman was ‘like making love to cold rice pudding’, Thorpe claimed. On one occasion he sodomised Scott against Selwyn Lloyd’s garden wall.

The bungled murder attempt on Exmoor is well known, but increasingly bizarre in retrospect. The failed assassin, Andrew Newton, who’d later become a rubber fetishist, initially went to Dunstable, mistaking it for Barnstaple. After he shot Rinka, the Great Dane, the gun jammed, so he fled. ‘They have shot my dog and they tried to shoot me!’ said Scott, covered in Rinka’s blood. Owing to his homosexuality – thus ‘hysterical, vindictive’ and ‘a dreadful pervert’– he was accorded little sympathy. That was the cruel line taken by George Carman, defending Thorpe at the subsequent trial in 1979. Scott’s evidence was worthless because he was weak, soft, poisonous and paranoid. Thorpe, by contrast, was ‘a statesman of courage and truth’ and, despite documentation of his lies, manipulation and financial embezzlement, was acquitted.

It was the greatest miscarriage of justice of modern times – Thorpe getting away with his murderous conspiracy through class bias, homophobia, hypocrisy and establishment cover-up. Scott says there was even talk of Thorpe’s wanting him chucked down a Cornish mine or dumped in the Florida Everglades. He is to be applauded, therefore, for surviving to have the last word. He deserves a medal for his resilience.

Comments