One implication of the Russian gas shut-off is that Norway has now become the EU’s largest single supplier of natural gas. According to the country’s energy ministry, they are expected to export 122 billion cubic metres of gas south to the EU over the course of 2022. This compares with the 155 billion cubic metres of gas which the union imported from Russia in 2021. Getting gas from Norway is obviously preferable to Russia: Norway is a friendly country, and Nato ally, and has gone out of its way to facilitate as much exports to the EU as possible. Over the summer, the country’s government effectively put a stop to a strike by gas platform workers that would have cut exports by around 60 per cent.

But Norway isn’t doing this out of the kindness of its heart. The Norwegian government and Equinor, the state-owned oil and gas company formerly known as Statoil, have struck rich. In the second quarter of this year, the firm made $17.6 billion (£15.2 billion) in pre-tax earnings, and returned $3 billion (£2.6 billion) to its shareholders. Since the Norwegian government owns two thirds of Equinor’s shares, that’s a pickup of $2 billion (£1.75 billion) in three months, or about $372 (£322) for each Norwegian man, woman and child.

Equinor’s cash-strapped buyers have looked at this windfall profit, and wondered if their northern neighbours might show some solidarity

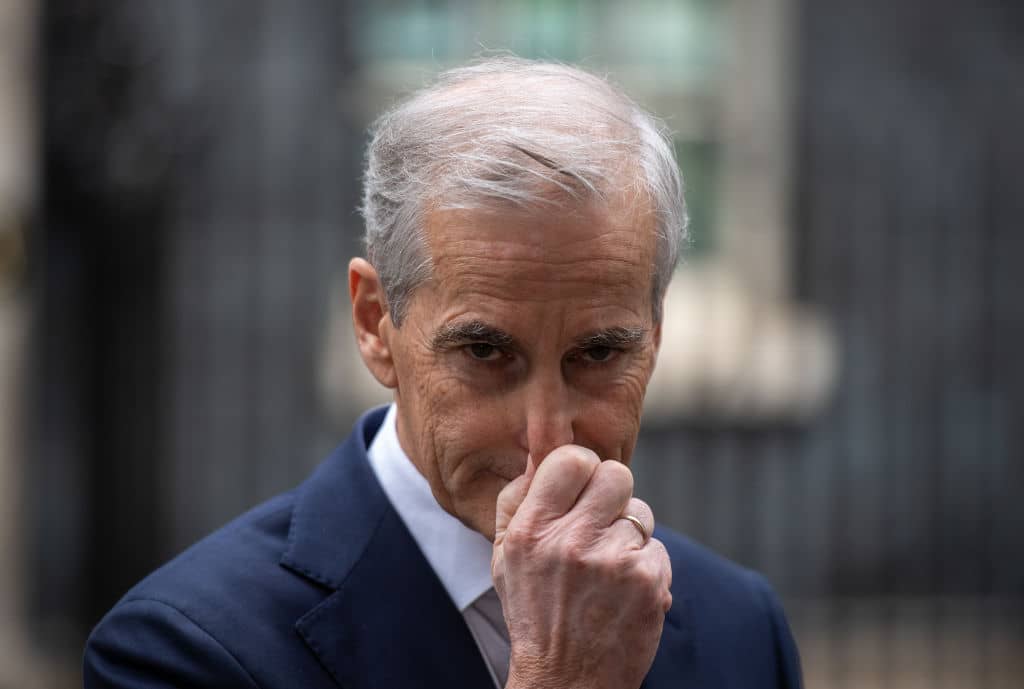

Naturally, Equinor’s cash-strapped buyers have looked at this windfall profit, and wondered if their northern neighbours might show some solidarity. But while the Norwegian government has said it would like to help, it has poured cold water on the idea of doing it through a discount on the price of gas. Jonas Gahr Støre, Norway’s prime minister, said of price negotiations that

‘We enter the talks with an open attitude, but are sceptical about a maximum price for gas. A maximum price will not do anything about the fundamental problem, namely that there is too little gas in Europe.’

His point here is twofold. Firstly, liquefied natural gas imports still account for more of the EU’s gas consumption than Norwegian pipeline-supplied gas does. Capping the price of that gas is practically impossible unless governments or the EU agree to pay the difference between the cap and whatever the prevailing market price for gas is, like the UK has done.

Secondly, some sort of price signal maintenance is arguably important to ensure buyers reduce the demand, since the problem is in fact not having enough gas. If you don’t let prices do that, the alternative is rationing.

While talks between Norway and the EU continue, it’s probably safe not to expect any price-capping. The Norwegian government is clearly not keen to limit its revenues in order to support what they see as a pointless endeavour. The broader lesson here is that there will be no easy answers to the energy crisis’s economic impact. The EU will collectively face tough decisions, and asking allies for help can only go so far.

Comments