Kafka was right: ‘Strange how make-believe, if engaged in systematically enough, can change into reality.’ But Barry Humphries, at the age of 76, manages much of the time to control his vacillating schizoid tendencies in nice equipoise. In his autobiography More Please, he stated that Edna Everage was a figment of his imagination. In this new ‘unauthorised’ biography of Dame Edna there are Kafkaesque indications that he believes she actually ‘has her being’, as he might put it. Like a ventriloquist’s dummy, she has long enabled him publicly to deride others in malicious innuendo that he would not have uttered in his less frivolous role of kindly Barry Humphries. However, as in other authenticated cases, the subterfuge is fragile: the creation sometimes dominates the creator, no matter how earnestly he attempts to maintain a semblance of normality.

At what may be described as the southernmost extremity of bipolar mood-swings, Humphries writes: ‘I wonder how I could ever have allowed one seemingly shy and uneducated woman to ruin my life.’ In fact, of course, she enhanced his life far beyond his most ambitious fantasy in the days when he was a Dadaistic transvestite student prankster at Melbourne University.

‘Melbourne was bisected by a class barrier,’ Humphries recalls. ‘Nice people lived south of it.’ He was brought up in the middle-class suburb of Camberwell. North of the River Yarra ‘dwelt nobody we knew or wished to know’. Yet Edna, a resident of Moonee Ponds, ‘a drab working-class suburb’, succeeded in persuading him by girlish postcard (green ink, circles over the i’s) to cross the barrier to witness her as Mary Magdalene, in a church-hall Passion Play. ‘One of the leads,’ she said, ‘along with God and Jesus.’ She sought Barry’s advice on acting and wanted him to manage her. After her performance, he thought:

If I could hire her for next to nothing to appear in one of my satirical stage shows she would be hilarious, even if she only read the telephone directory… This Edna could be the Eliza Doolittle to my Henry Higgins.

Thus was conceived an historic symbiosis. He observes:

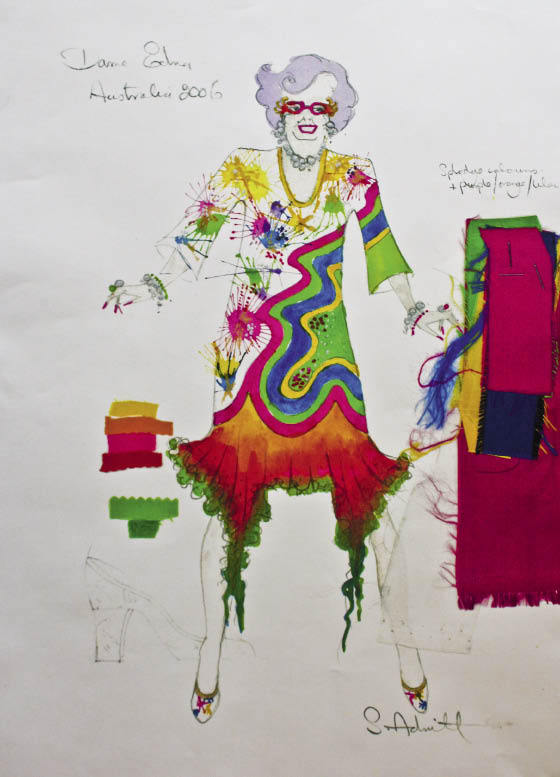

The change in her personality from a painfully reticent young housewife, barely able to conduct a conversation, to a terrifying monster looming over her theatre audiences like a vulture disguised as a bird of paradise, and a woman whose advice is today sought by world leaders, and whose clothes are shamelessly copied by First Ladies the planet over, is a transformation I could never in my most extravagant dreams have imagined when first we met.

That much of her fabulous life-story was already familiar to us devotees of the arts. We knew how Gough Whitlam, erstwhile Prime Minister of Australia, jestingly addressed her as Dame Edna, and how Queen Elizabeth probably formalised the damehood, ‘since by now Edna had forged strong links with Buckingham Palace’. There are new revelations in this biography which may startle the sensitive admirer, yet they enrich and humanise the established myth.

When Dame Edna attended a closed meeting of Megastars Anonymous she must have felt free to discuss her love affair with Frank Sinatra. ‘I already knew I was his type,’ she said, ‘since he had been married to Mia Farrow and we have the same bone structure.’ He called Edna ‘a classy broad’, always his highest compliment.

However, the encounter was fleeting. He left her naked in bed, she heard someone in the bathroom singing ‘My Way’, and a minder told her: ‘Get your clothes, lady. Frank’s busy but there’s an envelope on the hall table. Pick it up on your way out.’

With the proliferation of her international commitments, Dame Edna in later years rarely visited her home in Moonee Ponds, even when her unfortunate little husband Norm was still alive. A martyr to prostatitis, he was often bedridden, eased only somewhat by the ministrations of Marjorie Allsop, bridesmaid, babysitter and carer. Dame Edna was confident that nothing ‘improper’ ever happened between Madge and Norm because she was from New Zealand.

Even so, she wrote a letter, delivered posthumously, confessing that it was she, not a koala, that abducted the Everages’ baby daughter from her cot at Wagga, to reappear many years later as a nursing sister.

As a result of having been sexually molested in childhood by her Uncle Vic, Dame Edna has spent time in psychiatric care. She was confined in a secure hospital on the occasion of the Queen’s birthday concert in the garden of Buckingham Palace. As Dame Edna was counted on as mistress of ceremonies, Barry Humphries bravely served as her secret understudy, in the star’s make-up, the purple wig, butterfly spectacles, jewels and costume. The glamour of her appearance and his imitation of her falsetto voice were entirely convincing.

Humphries shares with Dame Edna the cosmopolitan savvy to drop the names of a lot of A-list celebrities; he sprinkles the text with big-dictionary words such as ‘emunctory’ (pertaining to the blowing of the nose), ‘immarcescible’ (unfading, imperishable, like Edna’s smile) and ‘omphalectomy’ (surgical excision of the navel); and the book’s appendix contains the lyrics of some of Dame Edna’s beloved songs, including ‘That’s What My Public Means to Me’. There are some good photographs of Dame Edna and Barry Humphries, two showing them sitting side by side, captioned ‘A Trusting Relationship’ and ‘Mutual Admiration’. Barry and Edna together constitute a viable single persona, with enormous talent.

Comments