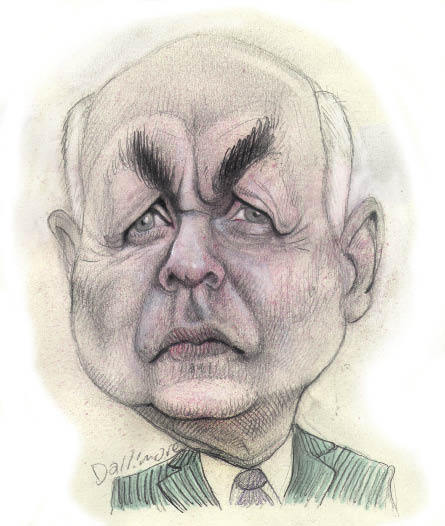

Iain Duncan Smith comes striding into his office with the look of a man who still can’t quite believe his luck. Even the very un-Conservative artwork on the walls of his office can’t dampen his spirits. He explains that it was the choice of his predecessor (‘what was her name? Ed Balls’s wife…’). Yvette Cooper’s choice of paintings, it seems, is not long for this world. ‘I’ll have to get some pictures of battle scenes,’ he says — looking at his aides with a mischievous grin. They, too, seem unable to believe that they have finally made it to the Department for Work and Pensions.

It is an unlikely nirvana. Most ministers inwardly groan when they hear they are being sent to the Department of Work and Pensions — a vast bureaucracy which has more ‘clients’ (as it calls those on out-of-work benefits) than Ireland or Norway have people. But for years, Mr Duncan Smith has been preparing for this moment. When he arrived, one of his first tasks was to review a Freedom of Information request lodged by a pesky MP. He asked his permanent secretary who the offender was. ‘He replied, “It’s you, Secretary of State, you’ve been on our back now for six months about this. I’m wondering, can I just brief you on this and end this issue?”’

Duncan Smith and his team have been feasting on data the government never released before which, they argue, shows how Labour’s approach to welfare failed. He is sitting in his office with his special adviser, Philippa Stroud, who also runs the Centre for Social Justice, a think-tank Duncan-Smith founded six years ago. He alternates between enthusiasm, and gulping at the size of the task now in front of him. At one point he even offers to swap places and join The Spectator.

One of the things that gives him hope is the civil servants who he believes are enthusiastically waiting to accelerate the welfare reforms started — to an extent — over the last three years. While the Blairite reformers complained about institutional resistance from their departments, Duncan Smith says he has been astounded by the appetite for reform. ‘It was almost as if I had lifted a lid off a pressure cooker,’ he says. ‘I realise now the frustration that this department has laboured under. They saw all the problems and, basically, were not really been able to say, “Let’s do something.” We may have to win a battle of ideas to put our ideas across, but the one thing I am not having to do is to persuade the officials here. I was astonished about that, really.’

His critique — developed through dozens of CSJ reports — is simple. That for all Gordon Brown’s talk, he did not fight poverty. Instead, his government spent 13 years seeking to manipulate a single metric: the number of people in Britain whose income was less than 60 per cent of the average. Money was spent moving people from just below the line to just above it, and those people were then declared to have been ‘lifted out of poverty’ even if their income had increased by only £10 a week. This approach, he says, led to the government feeding poverty rather than fighting it.

‘Brown was absolutely obsessed with targets. He loved to set a target up and then declare that he had met it. What then happened is that everyone in government narrowed their focus down to Brown’s specific set of targets. But what we have seen is an explosion of all sorts of problems elsewhere. We have seen residual poverty actually harden and now people in deeper poverty and the numbers increasing.’ He contends that Labour’s approach has been tested to destruction. The idea was that ‘if you throw money at it, then it will simply resolve the problem. And it hasn’t.’

His aim is to transform the DWP from a department that administers benefits into one which fights poverty. He recites what he told his staff on his first day. ‘Let’s get one thing clear from the start. I’m not here because I wanted another job that I couldn’t get. I’m here because this is the job that I really wanted. I am here with an agenda and it is one I hope you’ll join. I want this to become the poverty-fighting department in government, not the place that simply pays money out. Let’s make change work so that we can really do what you all wanted to do here — which is improve the quality of life for the worst off.’

Once, it was unusual to hear a Tory use such language — but Mr Duncan Smith has helped change the party he used to lead. When he set up the Centre for Social Justice, the very name of the organisation was a raid into what had been the language of the left. Its critique gave Mr Cameron the ammunition for his ‘broken Britain’ narrative, which included supporting marriage as the most effective provider of welfare. But Britain has heard promises about welfare reform before: from Tony Blair, John Hutton, James Purnell — why should there be progress this time? ‘Because the block was always Gordon Brown,’ he says. The former Prime Minister’s creation of tax credits — a system run by the Treasury — Balkanised the provision of welfare and prohibited any serious attempts at reform. ‘This department was left to struggle with some of the bits and pieces of the welfare system,’ he says. A full overhaul is required. ‘Unless we fundamentally change the system then we are going to be playing games for the next four or five years.’ He warns that if we don’t make the reforms and changes here, then ‘God help us in ten years’ time because the system itself will collapse under the weight of its own inertia and inconsistency’.

So what might fundamental change mean? There are 5.9 million on out-of-work benefits: a quarter of working-aged people in Glasgow and Liverpool and a fifth in Manchester and Birmingham are dependent on DWP payments. Duncan Smith’s proposals are all in the public domain — and the ‘most radical’ of these, he says, is that for the universal benefit. At the CSJ, he proposed abolishing all 52 current benefits — from incapacity to housing — and replacing them with a universal benefit designed entirely to make sure no one is better off out of work.

Now he has power, will this be government policy? He pauses. ‘All I can say is that we’re now working on all of that with a view to being able to see if it’s feasible.’ He thinks that a version of this policy — benefit simplification — is possible. But to put all benefits into one system would mean a bureaucratic upheaval on a scale Whitehall has not seen before — not to mention facing protests from those who would lose out. He is talking, I say, about the toughest task in politics. ‘I am — and I didn’t come to do anything else, to be honest with you. I am not interested in climbing rungs of ladders any more. That’s long gone.’

His years at the CSJ have left a long list of radical policies, which are not yet government policy. One example is Tesco’s recent proposal for a minimum pricing system for alcohol. When asked if he has changed his view, he pauses. Then, ‘Well, I’m on record on all this, so what the hell!’ he says. ‘I’m on the record for too many things. But my personal view is that the time has come to review this whole issue. The lives of too many children are being destroyed by an alcohol culture which is close to getting out of hand.’

On pensions, he says ‘it is an absolute imperative to start moving that retirement age up’. He sees an attraction in linking the state retirement age to risi ng life expectancy. ‘Ultimately, governments should head to that sort of process which is rather like the link between benefits and RPI inflation.’ He also wants to ‘get rid of this statutory retirement age, which is a ridiculous nonsense, because people are going to have to work longer’.

He makes no bones about his preference for a Conservative government to the coalition in which he serves. ‘Anybody who is a Conservative, or a Liberal for that matter, would have loved to have won the election outright. But you play the cards you’re dealt. The public knew what they didn’t want — Labour. But they couldn’t quite make up their mind that they wanted either a government by us or whatever.’ But the coalition, he says, is not without its advantages: it means automatic cross-party support for welfare reform.

‘I am a great believer in reaching out. There are lots of people in the Labour party who buy into this. When we did this originally [publish a CSJ report], I can’t tell you the number of people in the Labour party who came up and said, “We should have done this on day one.”’ James Purnell, he says, had a good record on reform when he was running the DWP. ‘If he had not had Big Brother sitting on his shoulder, I think we could have done business with him.’

Just as Tory ministers have not yet grown used to referring to themselves as the government, Duncan Smith still says ‘we’ to refer to the CSJ. As he knows, there is a gulf between what a campaigner can call for outside the system — and what a minister is able to do inside the government machine. Welfare reform is — along with school reform — the flagship Cameron project. He has been given a stellar team with Lord Freud, architect of the Labour reforms which he admired, and Chris Grayling, who pioneered the Tory welfare reform proposal when he was the Tory DWP spokesman.

He has the staff, the power, the ideas, the energy — so how fast can we expect to see progress? He gives no deadline. ‘I would be less than human if I didn’t sit here sometimes and think this is an overwhelming brief. Arguably the biggest one in government. It does cause moments when you sit and think, “How do I get this all to happen?”’ As he knows, there will be no one else to blame if he fails.

Comments