As exhibitions in London’s public galleries become increasingly mobbed and unpleasant, it is heartening to report that the drive to take art to the provinces continues apace. New museums seem to be opening all over the country, from Wakefield to Margate, and although one may entertain doubts about their sustainability, their enhancement of our current cultural budget is very welcome.

The latest public art gallery to open on the south coast is in Hastings, a once rather grand town that has in recent years been down on its luck. It takes more than an hour and a half to get there from London by train, and there isn’t a fast road, and these factors have contributed to keeping the town just outside the easy commuting belt. The consequent availability of inexpensive housing has long encouraged artists to live there, and there is a lively artistic community in the town.

Despite plummeting educational standards, I hope that everyone has heard of the Battle of Hastings, though not everyone will know that the principal engagement of the Norman Conquest actually occurred eight miles to the north of the town. However, Hastings has always taken the credit and its historical standing as one of the Cinque Ports was reinforced when it became a highly fashionable watering place in the mid-18th century, and later a popular seaside resort.

I first got to know Hastings more than 20 years ago through visiting John Bratby, who had bought himself an extraordinary pile called The Cupola and Tower of Winds, on the edge of the town. Hastings then was rather seedy. During the past decade there have been brave attempts to regenerate the local economy, with the building of the University Centre and the Sussex Coast College, and now the Jerwood Foundation has contributed largely to the cultural amenities by commissioning a new building to be its visual arts centre. This will be a venue for temporary exhibitions as well as the base for the Jerwood permanent collection.

The £4-million building, designed by HAT Projects and clad with grey-black ceramic tiles hand-glazed in Kent, makes a striking statement at the edge of the fishing beach. The tiles work well with the tall black weatherboard net huts, such a feature of the area. Inside the gallery is a large ground-floor space for temporary exhibitions, with a succession of seven smaller rooms (down and up) where the permanent collection will be hung in rotation. These spaces have been sympathetically laid out, with top-lighting as well as windows through which to view the world outside. The domestic scale of the rooms mirrors the domestic size of the paintings in the permanent collection — the quality of which is one of the chief surprises of this venture.

I knew the Jerwood Foundation had collected some paintings, but I must confess I had no idea of the extent and variety of its holdings. About one third of the collection is currently on view, and it ranges from Frank Brangwyn’s combination of still-life and landscape, ‘From my Window at Ditchling’, c.1925, the first painting bought for the collection, to Maggi Hambling’s powerful yet poignant portrait of her elderly neighbour, ‘Frances Rose’ (1973). The focus is on Modern British and the artists who won the Jerwood Painting Prize, but the character of the works is frequently unexpected. Obvious examples of an artist’s style have often been eschewed in favour of an unusual image that packs a slightly different punch. Thus, downstairs is a marvellously minimal William Gear abstract landscape, simply a slightly angled thin red line dividing areas of subtly modulated brown and black. Upstairs is a splendid and atypical landscape by Mark Gertler, of an Irish yew at Garsington.

Among the other glories are a lovely Shropshire landscape by Ivon Hitchens, a hard-edged wartime still-life by John Craxton and good things by Augustus John, Frank Dobson, L.S. Lowry, Bratby, Alan Reynolds and Robert Medley.

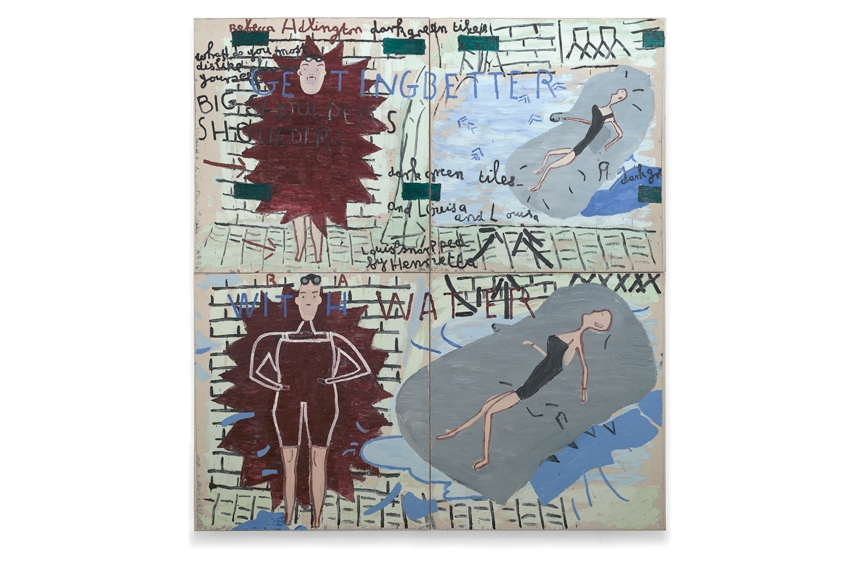

The temporary exhibition space is devoted to paintings by Rose Wylie (born 1934), bold figurative images of uncompromising directness. Wylie confronts head-on our society’s lemming-like tendency to banality, and makes witty comments on our obsessions with style, time, image and self-image. Her practice is based firmly in the probity of drawing and her wry observations of human behaviour. This linear language is then translated to large, loosely painted canvases, in a style that takes the term ‘short-hand’ to new levels, mixing the narratives of film and cartoon with vigorously expressive paint-handling. Wylie points out her admiration for the Bayeux Tapestry, and the empty canvas backgrounds to the action (so like her own), and this Norman connection makes it even more appropriate that she should have the inaugural exhibition at this impressive new gallery.

Back in London, let me draw your attention to two exhibitions that I have already written about, inasmuch as I’ve contributed essays to their accompanying catalogues. Both are in West End commercial galleries, where some of the most interesting shows come and go with scarcely any coverage in the nation’s press. Only a favoured few galleries (such as White Cube and Gagosian) tend to receive regular reviews, for the simple reason that they show artists who are currently fashionable.

Yet a few years ago there was good coverage of what went on in London’s large community of private galleries — because it was recognised that they presented a wide variety of high-quality art, and it was thought that the art-going public would be interested in knowing what was available. The official view today is very narrow, severely limited by fashion and vested interest. There needs to be more written about the sheer diversity of art on offer in the capital — not the same old handful of exhibitions reviewed by all the critics.

At Browse & Darby (19 Cork Street, W1, until 5 April) is a delightful exhibition of oil paintings, gouaches and lithographs by the French artist Henri Hayden (1883–1970), once well known here, but now generally unfamiliar. His work was shown a lot in London in the 1960s, he’s well represented in the Tate, and it’s clear that some of our contemporary artists were aware of him (Mary Fedden, Rose Hilton, Craigie Aitchison). Hayden was a Polish refugee who settled in Paris and worked his way through the influences of Renoir and Cubism to a brand of very pleasing lyrical landscape painting. His simplified forms and plangent colours were applied to still-life as much as landscape, and offer a beguilingly abstracted and poeticised approach to subject matter.

Meanwhile at Redfern Gallery (20 Cork Street, W1, until 26 April) is a show of new work by Ffiona Lewis, entitled Figurine and Landscape. Lewis (born 1964) has already built up a loyal audience for her distinctive landscape and still-life paintings, often attractively light-filled and celebratory. Her recent work builds on these firm foundations (her approach is decidedly structural — not surprising for a painter who trained as an architect) and tackles her subject with new authority.

She has been spending a lot of time recently in Suffolk, which she sees as much softer and darker than the Atlantic coast of Devon and Cornwall where she grew up. Her landscapes have become correspondingly darker as she has explored the presence of black in her creeks and meres and tree-scapes. These powerful new works, with their complex echoes of both classical and romantic (from Claude to Paul Nash), are moving beyond the familiar Lewis territory of still-life and landscape towards a new ingredient: the human figure. As yet the figure appears mostly as sculpture or figurine, but I feel this is a new direction for Lewis, rich in possibilities. All three shows are highly recommended.

Comments