‘Isn’t Naples beautiful? I’ve always dreamt about it. I always wanted this city all for myself; I didn’t want to share it… I alone deserved it because of everything I lost and I would have done anything to get it.’ So says Ciro Di Marzio – nicknamed ‘the immortal’ because he has survived so much mafia bloodletting – in the hit TV crime drama Gomorrah.

He is not talking about the churches or castles, the arcades or theatres or museums. He may have been out on the bay at night when the words are uttered, but the Naples he knows, grew up in and by then controls is the Naples of Scampia and Secondigliano, places up on the ridgeline of the city: the Naples of high rises and concrete, the Naples of drugs and murder.

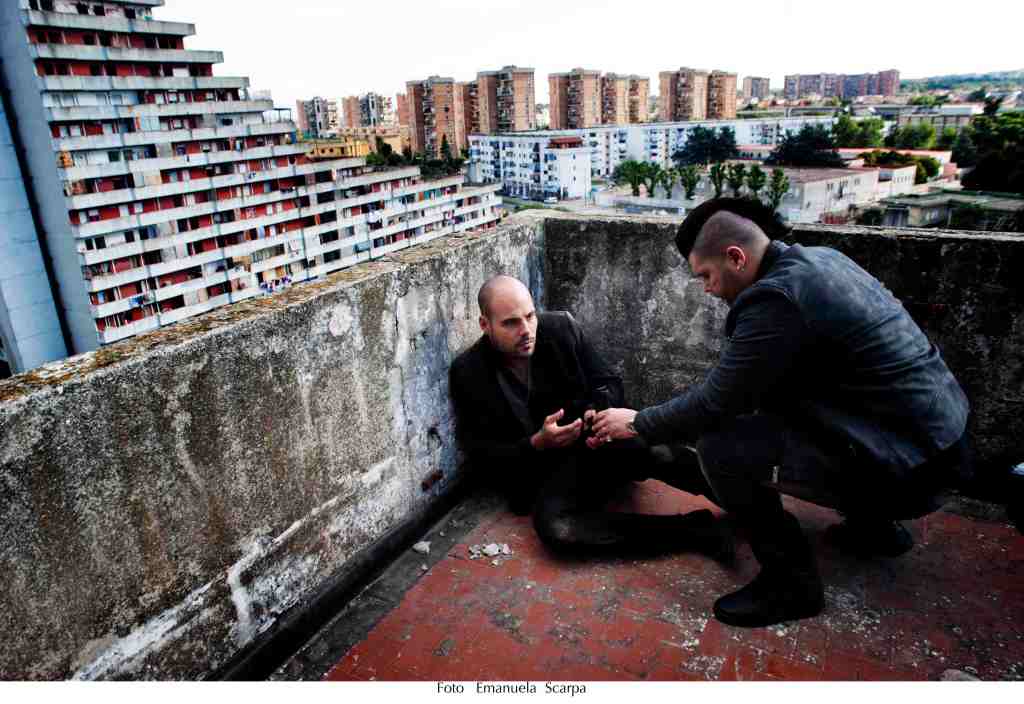

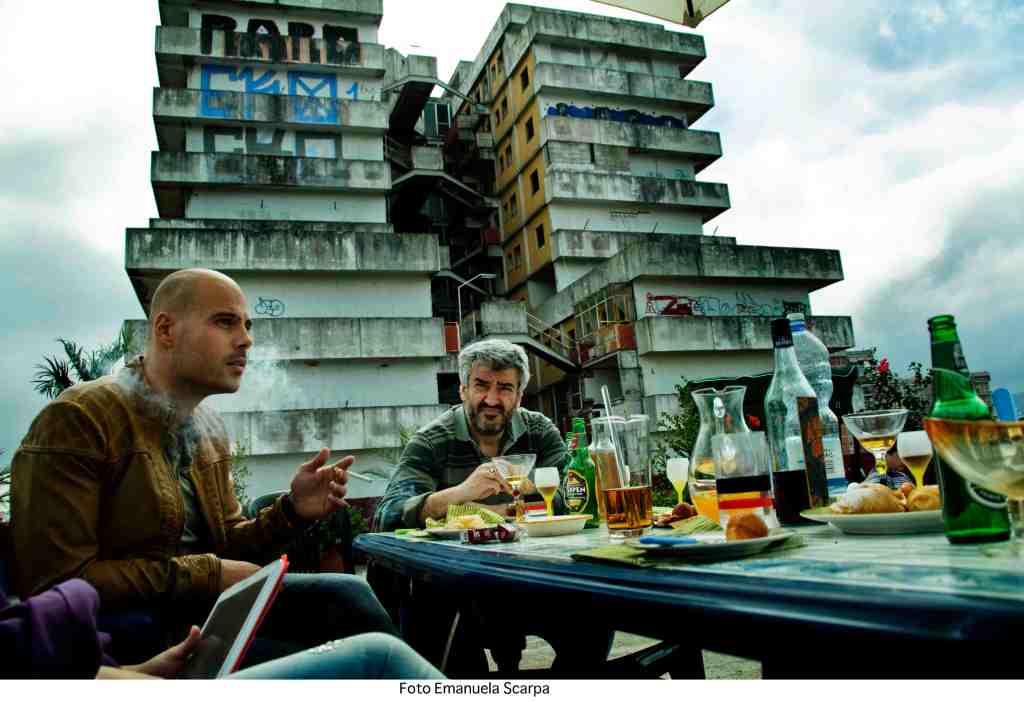

Gomorrah, shown on Sky, quickly became a commercial and critical success, eventually distributed to 190 countries. It has always been a loosely fictionalised version of real life, adapted from the non-fiction book of the same name by Roberto Saviano, and part of its appeal is its authenticity. The characters speak in the local dialect, so much so that Italian viewers also get subtitles; the violence is largely based on historic crimes; and the action is filmed on location, specifically at Le Vele, the seven large residential complexes that resemble the steep stepped sterns of the huge cruise liners that visit the port below and disgorge tourists towards Vesuvius and Pompeii.

If characters such as Ciro and his nemesis Genny are compelling, it is partly because they are rendered sympathetic by the hellscape in which they exist, one that is all too real. At the heart of the fiction and the non-fiction is Le Vele – the Sails – once the largest open-air drug market in Europe, worth an estimated £200 million a year in profit to the Camorra gang that controlled it. So it’s a story about many things: the absence of government, the presence of organised crime, the unwinnable war against drugs, but also how architecture can lead to poverty and even perhaps hope. And that’s also the story I went in search of when I visited Scampia.

Le Vele, as you might expect, started off as a good idea with a beautiful name. Built between 1962 and 1975 on an area that had largely been fields, it was designed by Franz Di Salvo, the modernist and urbanist, as a peculiarly Neapolitan utopia, recreating the narrow but sociable alleys of the historic city centre through a web of staircases and balconies connecting the two great terraced blocks that made up each triangular sail.

Immediately it went wrong. The blocks were placed too close together, crushing the community areas. The wrong type of sand was used in construction, through carelessness or corruption – the ostensible reason why the blocks are now being demolished, with four gone and another two slated to join them; one will remain as a sort of ghoulish memorial to a time when there were up to 100 murders a year, the months when there were one a day. And the things that make a community viable, such as schools and stations and shops and hospitals and playgrounds, were never built. And then there were the huge boulevards that separated them, today cluttered with bits of broken kerbstone.

Part of Gomorrah’s appeal is its authenticity: the characters speak in the local dialect, so much so that Italian viewers also get subtitles

Mirella Pignataro, 83, was an early resident. The wife of Felice Pignataro, a local artist whose vivid designs cover the nearest metro stop at Piscinola and who died in 2004, she moved to Scampia in 1972 from the rich suburb of Vomero after the couple got married. Greenery is in short supply in Naples and at first it seemed refreshing: there was room to breathe, trees, sky. ‘But it was built in a bad way,’ she says. ‘It was a place to sleep, not to live. There was nothing there, just big towers, wide, dangerous streets with many car accidents. But after [the bomb damage of] world war two there were so many people waiting for houses.’

In 1973 she started an association to bring in food to sell to the locals in the absence of proper shops, to change things for the better, and for a while it looked like they might succeed. And the Camorra, always a part of life in Naples, was still mostly focused on smuggling contraband cigarettes.

Then came the earthquake of 1980, which left at least 2,483 dead and 250,000 homeless. ‘With the money for reconstruction, the Camorra and the corrupt politicians became rich,’ she says. ‘The mafia became king.’ Of the $40 billion spent on reconstruction, only a quarter reached the people who needed it. And the Sails began to overflow with the homeless. The unfinished spartan apartments were squatted. Scampia became a ghetto.

At the same time, a man called Paolo Di Lauro was rising to the top of the Camorra. ‘The old mafia didn’t want to sell in Scampia,’ Mirella says. ‘But Di Lauro saw the money that could be made from drugs and did deals with Pablo Escobar and brought in cocaine from South America.’ And Di Lauro, a reclusive man with a talent for numbers and gambling, also had an architect’s appreciation for space: he saw how he could use Le Vele. How easy it would be to split the cramped blocks into dens for dealing, how the wide boulevards made communication between neighbours impossible but provided warning of raids. And he saw how the cops just drove round and round, if they went there at all, how the fire brigade couldn’t find the flames they were supposed to put out. And that there were many people who had not gone to school that he could use as mules or sentries.

‘It was a slow change, and people didn’t notice at first because they lived from day to day,’ Mirella says. ‘But a silence descended.’

Some tried to fight back: Mirella and her husband started a carnival in 1983 to try to forge the sense of community that had existed in the old neighbourhoods. The first year, ten people attended. Now it is in its 40th year. ‘We wanted to create a tradition,’ she says. ‘We made a loud noise with whatever we had. Now people will notice if we stop.’

But the winds of change that shook the Sails could only come up from within the Camorra itself, always the most anarchic of Italy’s mafia, with its metastasizing cliques and transitory allegiances. There was an early hint of what was to come when Di Lauro – the inspiration for Don Pietro Savastano, Genny’s ruthless father in the TV series – briefly lost control in 1992 after one of his captains, coming back from prison, found his lucrative dealing operation in a piazza had been awarded to another. He gathered his crew and struck at Di Lauro’s men with assault rifles, killing five and wounding nine. Di Lauro’s men hit back, murdering most of their former associate’s family. With some difficulty a ceasefire was imposed by 1994, but the police had begun to take an interest.

If characters such as Ciro and Genny are compelling, it is partly because they are rendered sympathetic by the hellscape in which they exist, one that is all too real

Yet the code of silence thwarted them for a decade until a larger civil war broke out in 2004. Di Lauro had gone into mourning after one of his 11 sons was killed in a motorcycle accident; he ceded operational control to his eldest, Cosimo, a bully who lacked his self-discipline and strategy. The 30-year-old almost immediately managed to alienate all the long-established underbosses of the clan, who broke away to form their own gang. The explosion of violence was dazzling. That winter 54 people were killed, but what finally loosened tongues was the torture of one of the separatist’s girlfriends, murdered and burned in a car. The police swooped for Cosimo. In 2005, they found his father hiding in the apartment of an old woman.

If the government was starting to realise it could not just ignore the outer suburbs of Naples any longer, given the cycles of internecine warfare that predictably broke out in the vacuum left by Di Lauro in the following years, something else would also force their slow hand. In 2006, Saviano, a journalist and native, laid bare the inner workings of the Camorra in his non-fiction book Gomorrah, on which the TV series is based. It became an overnight sensation and sold four million copies; Saviano went into police protection.

The raids started. Up to 1,500 cops descended at a time. Sometimes there were soldiers too, erecting roadblocks and checkpoints. They fought the dealers and the hoodlums over the gates: hundreds had been put in place to facilitate the drug trade. Through them heroin and cocaine and money passed, but not people. The dealers put them up, the police pulled them down. They made loopholes in the concrete too, just big enough for hands to pass and take. Balconies became escape routes, the upper floors hideouts and sanctuaries. The crime and the architecture were intertwined.

‘The cops understood they had to destroy the gates,’ says Dani Sanzone, the lead singer of A67, a rock band named after the Italian law that governs urban planning and the provision of social housing. ‘And the bosses understood that when they came down, they would have to move. Now they are in other areas of Naples that get less attention, like Melito. You used to see druggies here all the time. You don’t see many any more.’

Technology has also played a role. Sanzone, whose family moved to Scampia after the earthquake and whose image also adorns the interior of the Piscinola station – one of the local boys made good – tells me: ‘Drug sellers have now moved to social media – getting drugs is as easy as ordering pizza.’ And nowhere does pizza like Naples.

Sanzone has an interesting relationship with Scampia – he likes the scruffy greenery, what there is of it, and, like his 16-year-old niece, who translates for us and wants to study physics, can’t imagine leaving an area where all his friends live. But he recalls being threatened by one of Di Lauro’s sons when his song ‘I am Camorra’ came out. ‘He thought we were mocking them,’ he says. ‘I didn’t sleep for a week. Eventually someone I knew, a dealer, told him we were just a bunch of guys who had read too many books.’

Yet he is surprisingly hostile to the TV series, much of which was filmed in Le Vele and which made Scampia famous – the instantly recognisable Sails have almost as big a starring role as the actors Marco D’Amore, playing the antihero Ciro, and Salvatore Esposito, who brings such menace to Genny. ‘It may be based on things that happened, but it didn’t show reality, and it was always a negative point of view,’ he says. ‘And it is still dangerous for us: those characters could become role models for the young here.’ Indeed Luigi de Magistris, the former public prosecutor and mayor of Naples, claimed there was a huge spike in violence every time an episode was shown, and said Gomorrah was ‘likely to corrode the brains, souls, and hearts of hundreds of very young people’.

“I want people to know that Scampia isn’t like Gomorrah,” Sanzone adds. “There are still drugs here but in 20 years it has all changed.’

One of the key factors he cites is an ambitious programme of redevelopment that has seen the Federico II University of Naples move into the area, occupying a tract that formerly contained one of the Sails. More than 4,000 students will soon attend a new medical faculty, although the brown brick drum of the new building is about as inspiring as the one it replaced. ‘With the influx of students, the whole mindset of the area will change,’ Sanzone says. ‘The university brings real hope.’

Mirella agrees: ‘Yes, I have hope for the future. I have hope in the teenagers, that they will get to enjoy the changes after all these difficult times.’

And the notorious Le Vele? Should they remain? Four have already been demolished, and of the three standing, only one is earmarked to live on, like a grey, slanting tombstone, a warning against bad planning, bad construction, bad design. How much is down to the buildings themselves? How much are they to blame for the years of horror?

‘The project was a good one,’ Mirella says, ‘because the architect wanted us to live in light, but died [in 1977] before they could be completed. But they turned out bad. They were badly built, there was no light, and they turned into prisons. It’s right they’re being demolished. But Le Vele are not the symbols of those times – those will always be the bullet and the gun.’

Comments