[audioplayer src=”http://traffic.libsyn.com/spectator/TheViewFrom22_12_June_2014_v4.mp3″ title=”James Forsyth and Isabel Hardman discuss the English question and the next election” startat=1129]

Listen

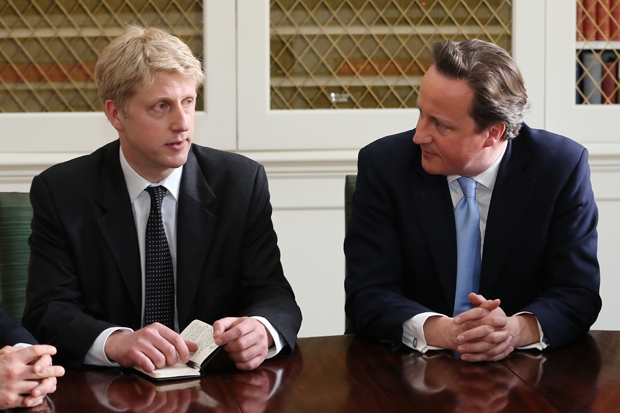

[/audioplayer]Before David Cameron heads off for his summer holiday, he’ll be presented with a first draft of the Tory manifesto by Jo Johnson, Boris’s younger brother and a cautious, well-organised thinker. He dislikes publicity almost as much as the Mayor of London relishes it. Radical ministers lament that Johnson doesn’t like pushing their recalcitrant colleagues too far, but despite this, the early hints are that the manifesto will be a surprisingly bold document.

There will, though, be one thing missing from this draft: what to do about the English question. A member of the Tories’ home affairs manifesto committee group says that the subject was considered too contentious to discuss before the Scottish independence vote on 18 September.

This caution is understandable. Any plan to bar Scottish MPs from voting on certain issues would have been grist to the nationalist mill. But there are several reasons why the Tories do need to start thinking about this question.

First, it now looks more likely that the Scots will vote No. The Unionist campaign is in far better shape than it was two months ago, when the Cabinet was holding panicked discussions about its failings. Perhaps the surest sign that it is on course for victory is Gordon Brown re-emerging on to the Westminster political scene to discuss the issue. ‘There is going to be an almighty clash of egos to claim credit’ once the referendum is over, warns one member of the shadow Cabinet. One can’t imagine Brown taking kindly to Alistair Darling going down in the history as the man who saved both the British banking system and the Union from collapse.

Even if Scotland votes No, more powers will move to Holyrood. Cameron has already endorsed a new devolution deal that would grant the Scottish Parliament power to vary all elements of income tax except the personal allowance. The political logic behind this proposal is compelling. The Tories know they will only be able to recover north of the border when Scottish politics becomes about how to raise money as well as how to spend it. A Scottish Tory party that stood for lower taxes could begin to reconnect with the country’s middle class.

But if the Scots are granted these powers, then the asymmetries in the Union will become even more profound. The Welsh Tories are already pushing for a similar arrangement.

It has long been said that the answer to the West Lothian Question — why Scottish MPs should be allowed to make law for England, if English ones can’t make law for Scotland — is to stop asking it. Even if this riposte was credible once, it isn’t now. Ukip, as Nigel Farage emphasised to The Spectator recently, wants a federal UK with a separate English parliament. It would be a major strategic error for the Tories, or Labour, to allow Ukip to claim that it is the only party proposing a ‘fair deal for England’. This is particularly true, as a close vote in Scotland followed by more devolution could well prompt a backlash in the rest of the United Kingdom.

The last Tory manifesto promised to address the West Lothian question. It declared that ‘a Conservative government will introduce new rules so that legislation referring specifically to England, or to England and Wales, cannot be enacted without the consent of MPs representing constituencies of those countries’. But in government, this agenda has been kicked into the long grass. When the Tory MP Harriet Baldwin tried to push it through a private members’ bill and various parliamentary interventions, it was made known that if she wished to advance in her career, she should drop the matter.

But this attitude won’t be tenable while a new devolution deal for Scotland is being negotiated and as the Welsh Assembly begins to use its new powers. So, what the Tories say in their manifesto on the subject will matter far more than before. The Liberal Democrats, who remain their most likely coalition partners, want a fully federal UK. But it is clear that there won’t be cross-party agreement on any new devolution deal because Ed Miliband is determined to oppose any settlement that allows tax competition between Scotland and the rest of the United Kingdom. This competition is an integral part of both coalition parties’ plans.

The problem with federalism has always been that England is just too big. An English parliament would represent more than four fifths of Britons and would instantly become a competitor to the UK parliament. There would be a constant battle for political supremacy between the English First Minister and the British Prime Minister.

This is why the last Labour government was so keen to promote the English regions, which are a far more manageable size. But the English have shown a cussed refusal to accept devolution to their regions and cities. John Prescott’s proposed North East Assembly was soundly defeated and Cameron suffered a rebuff when nine out of ten English cities rejected his offer of a directly elected mayor.

Whatever form a federal structure eventually takes, it will require far more effort to be put into promoting Britishness. People must know the ties that bind this nation together. Without this, the constituent parts of the UK will end up living separate lives under the same roof; something that will — in time — lead to separation. Indeed, part of the problem for the Unionist campaign in the Scottish referendum is how little Westminster-based politicians know about what is happening north of the border. This makes them hesitant about participating in the Scottish debate.

An emphasis on Britishness will help with integration, too. For too long, there has been a glib assumption that if you have to ask what Britishness is you don’t understand it. This, to put it mildly, is not helpful to immigrants to this country. It is much easier to be an engaged citizen if you know how Britain came to be a parliamentary democracy with the common law and a constitutional monarch.

The constitutional tinkering of the past 20 years has been a disaster. Devolution has not killed nationalism in Scotland, as its architects imagined, but led to a referendum on independence; it has also done nothing to improve the lives of Scots. The new constitutional settlement that will be required after the Scottish referendum will have to be both comprehensive and fair. To assume that the English question doesn’t need answering would, in this age of Ukip, be to take an awful gamble with the Union.

Comments