The weekly ONS infection survey suggests that the rise in prevalence of Covid-19 in England has levelled off. Not only that, it suggests that the rate of new infections has actually fallen.

In the week to 31 October, the ONS estimates that 618,700 people had Covid-19 — about 1 in 90 of the population. That was up from 568,100 the week before — a 9 per cent increase. However, it amounts to a stark slowdown on previous weeks. At that rate, it would take eight weeks for the number of people with Covid-19 to double — a long way from the doubling rate of eight to ten days which was observed in September.

As with all Covid-19 data, caution needs to be applied

As for the new incidence rate (an estimate of the number of people who caught the infection during the seven days to 31 October, as opposed to the number of people who were positive for the infection at some point over the seven days), the ONS estimates that it has fallen: from 9.52 per 10,000 in the week to 23 October to 8.38 per 10,000 in the week to 31 October.

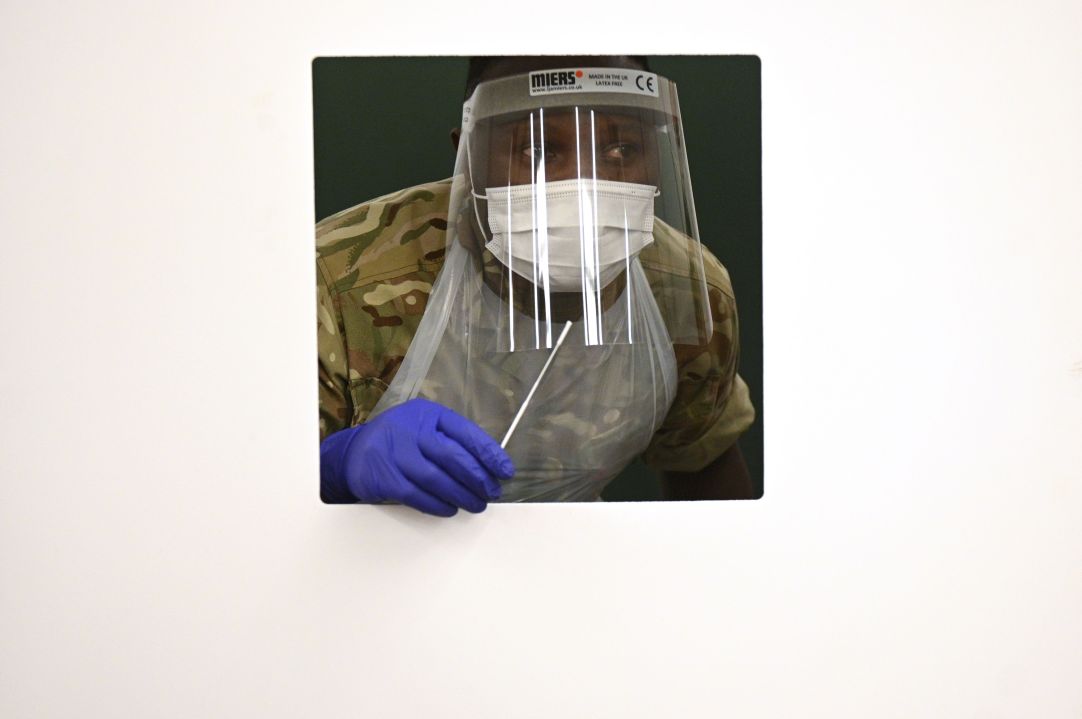

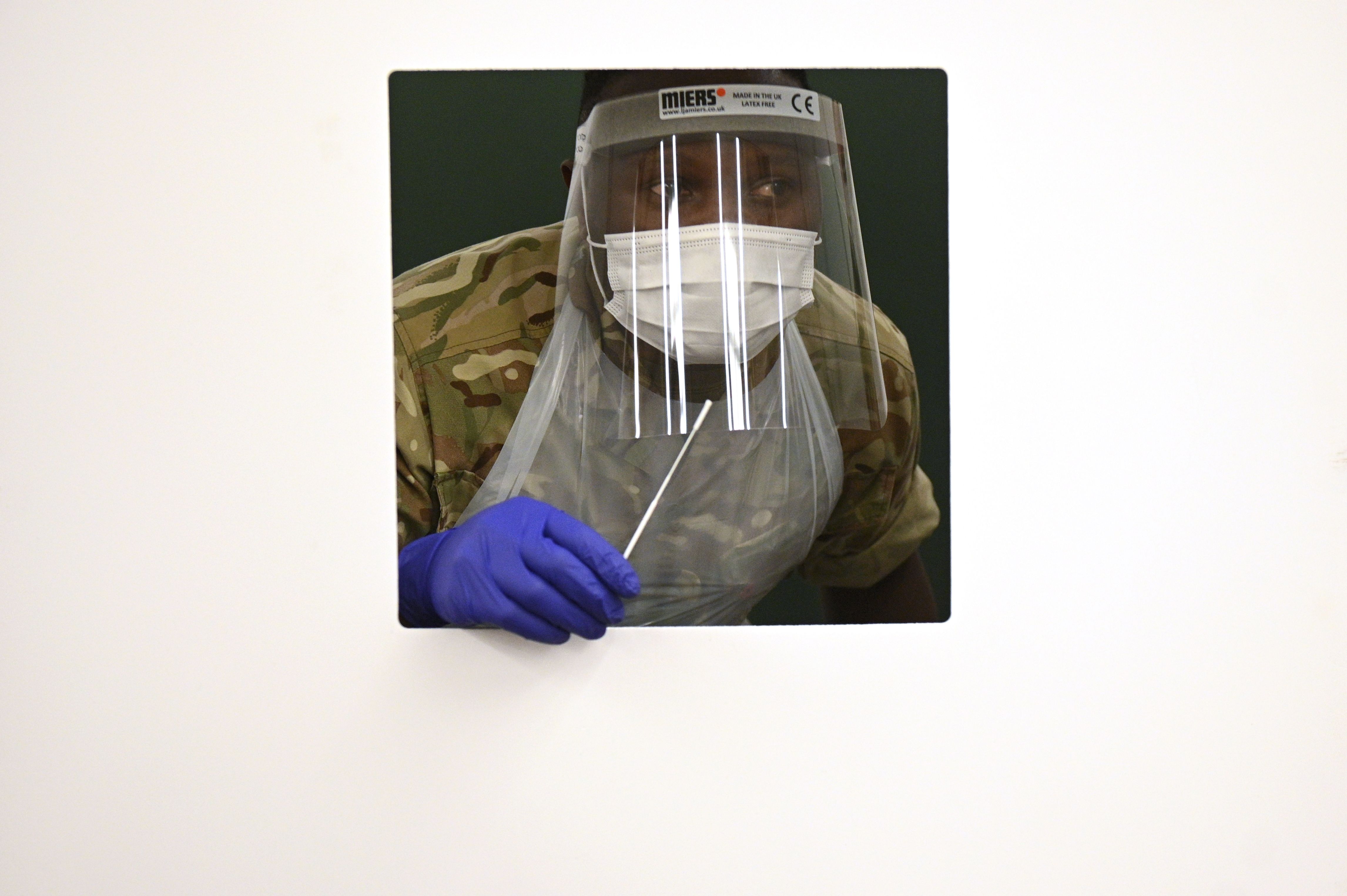

As with all Covid-19 data, caution needs to be applied. Once before, in late September, the ONS data showed a levelling off of prevalence and a fall in the rate of new infections — only for both to accelerate again. Nor does the ONS survey tell us what is going on in hospitals and care homes. Nevertheless, it is about the best data source we have for the prevalence of Covid-19 in the community. It is based on swab tests on a randomised sample of 650,000 people. It therefore captures infections that will have been missed by the normal testing regime, which is unlikely to pick up the many asymptomatic infections (between 30 and 80 per cent of the total, according to various estimates). Nor is it affected by the expansion in the number of tests.

The Public Health England figures for confirmed infections also show a levelling off in new infections. In the week to 5 November, the seven-day average for new infections was 22,551 — virtually unchanged from the 22,124 a week before. While deaths are still rising, they are a lagging indicator — they reflect the rate of new infections three or four weeks ago.

It all begs the question: if the Prime Minister had had his eye on the real data, rather than the projections for deaths which were already several weeks out of date, would he have called a national lockdown? What evidence we have suggests that the regional tiered approach was already causing infections to level off — especially in tier three areas such as Liverpool and Nottingham where new cases have plummeted over the past week.

Comments