‘It’s odd,’ Picasso once mused, ‘but you never see Modigliani drunk anywhere but at the corners of the boulevard Montmartre and the boulevard Raspail.’ He obviously suspected his friend of being a stage bohemian. There is, indeed, a touch of Puccini about Modigliani’s life — the poverty, his film-star good looks, the drink and drugs and poignant early death, all set against a picturesque Parisian backdrop of Montmartre and Montparnasse. It’s La bohème but with the painter himself, surely a tenor role, taking the place of the tragic, tubercular Mimì.

Whether or not he lived out a cliché, Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920) certainly painted to a set recipe — even if it was one largely of his own devising. The new exhibition at Tate Modern, nicely hung and ingeniously arranged though this is, can’t quite disguise the fact that as an artist Modi was highly repetitive.

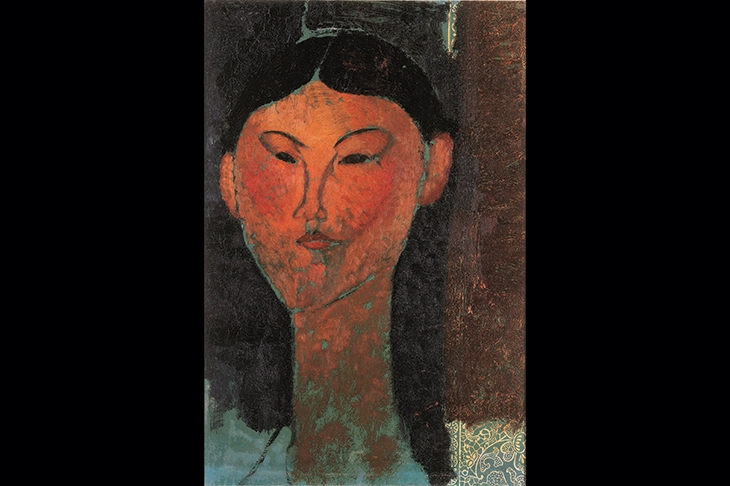

Mind you, his formula is good — at least in small servings. One or two prime Modiglianis are a fine sight: the linear design is rhythmic, the application of paint succulent, the colours zing (apparently, the quality diminished when he painted under the influence of hashish). But when a row of similar works are lined up, side by side, you notice that his sitters have been Modigliani-ed. The elongated neck, almond eyes — often blank and pupil-less — and swan neck are combined with just enough individuation to make each approximate to a likeness.

When you get to the nudes, everything really goes pear-shaped (sometimes literally). These aren’t quite erotica — the artfully schematic faces save them from that. But they belong to an area of winsome early modernism that brings Playboy centrefolds to mind. After you’ve seen a few — and the Tate has corralled a sizable group — you start to think, ‘Oh no, not another!’

It’s off-putting when looking at these to recall that Modigliani was a brutal, angry drinker whose behaviour to his lovers was so bad that these days he’d be drummed out of public life. He once threw the writer Beatrice Hastings, with whom he had a long affair, out of a window. The poet André Salmon wrote a celebrated description of his treatment of the last woman in his life, Jeanne Hébuterne, 14 years his junior and pregnant with their second child.

Salmon saw the painter dragging her along by an arm, ‘gripping her frail wrist, tugging at one or another of her long braids of hair, and only letting go of her for a moment to send her crashing against the railings of the Luxembourg’. Salmon felt he was ‘like a madman, crazy with savage hatred’. Perhaps Modigliani really was mad by that stage; he died shortly afterwards of tubercular meningitis.

Poor Jeanne killed herself two days later, jumping out of a fifth-floor window. Modigliani’s pictures of her form an unsettling group. In a few, such as ‘Portrait of a Young Woman’ (1918), you seem for once to encounter an individual personality — a nervous near-schoolgirl. In others, she’s been homogenised into an elegant near-abstraction of gazelle-like curves.

On this evidence, Modigliani’s sculpture was the best of his work. The Tate has amassed a whole room of it and in this case, unlike that of the nudes, the sum of the whole is greater than the individual pieces. Jacob Epstein reported visiting Modigliani’s studio at night and seeing these stone carvings arranged, each with a candle on its top, as in ‘a primitive temple’. This is less atmospheric, but has a similar effect.

Again, these are variations on one — or at most two — themes. The best are like updated and feminised Easter Island heads — thin-as-a-blade, noses like downpipes, acorn eyes. This image was a blend of sundry ‘primitive’ sources — Gauguin’s South Pacific, a touch of Angkor Wat, a hint of India. But it works. The Tate’s own ‘Head’ (c.1911–12), for example, is strong — near the class of Modigliani’s sculptor friend Brancusi.

These 3D pieces succeed better than the paintings generally do. The reason is perhaps that they don’t pretend to be anything but stylised inventions; there’s no awkward reconciliation of the formula with a real person. However, Modigliani concentrated on sculpture for only a short period. There was no development, any more than there is in the paintings. Having found his trademark head, he stuck with it. He was one of those artists who turn out a product — one, to judge from the crowds at Tate, that is still highly popular.

Modigliani’s was, admittedly, a short career — not much more than a decade — but it’s hard to imagine that he would have changed very much if he’d lived to be 90. He’d still have been painting people with goose necks and boiled sweets for eyes. His sad but glamorous existence disguises the fact that, in quantity, he’s a bit of a bore.

Comments