Normally foreign policy is the refuge of poll-losing leaders, who have tired of the slow pace of domestic reform and launch themselves unto the international stage in the hope of a restoration.

Normally foreign policy is the refuge of poll-losing leaders, who have tired of the slow pace of domestic reform and launch themselves unto the international stage in the hope of a restoration.

Even if electoral rehabilitation is unlikely, the Club of Leaders is a more collegial place than the domestic political scene. Think Bill Clinton in 2000. Or the world-strutting Tony Blair.

Even Gordon Brown, whose interest in foreign affairs is clearly limited, has sought to build an international profile, in part to help him at home. He hasn’t done it like Tony Blair, who would be jetting round the world trying to solve the Russian-Georgian War. But the PM has taken a lead on issue he cares about like international development, and world finance. The PIPA global polling data on trust in world leaders puts him in second place behind Ban Ki-Moon.

But whilst leaders may begin looking abroad, opposition leaders tend to stay at home, scoring points on bread-and-butter issues. Partly this is practical: prime ministers can meet other prime ministers and get good media coverage but. nobody is interested if opposition leaders confer, unless they are about to be elected. (The exception may be U.S legislators, but the U.S Congress has a statutory foreign policy role unlike in parliamentary democracies.) Opposition parties are also usually hesitant to commit themselves to specific policies in foreign affairs, especially in a world as fast moving as ours.

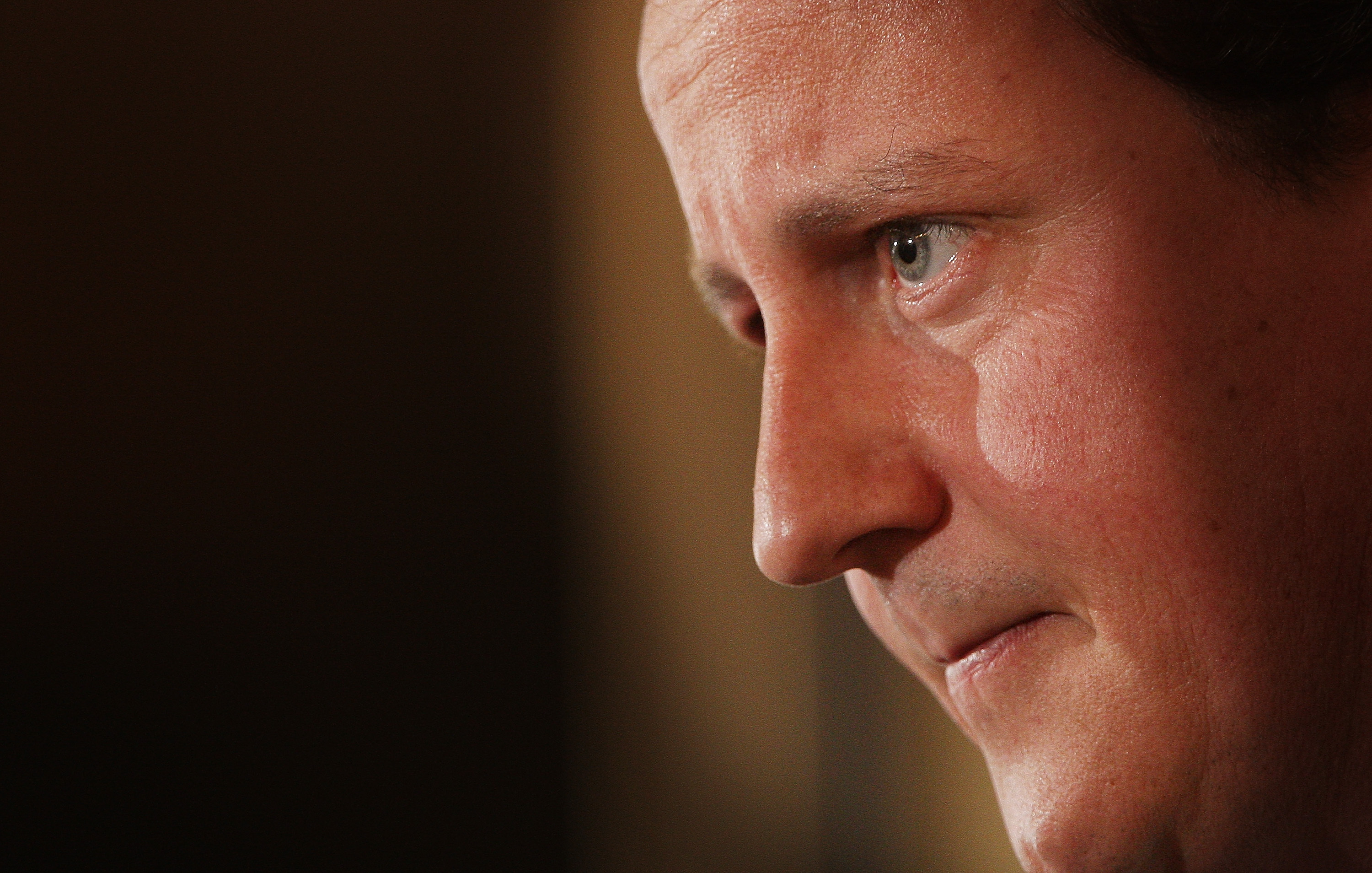

It is all the more interesting, therefore, that David Cameron has begun bigging-up his international role. Previously described by commentators as someone who does not “do” foreign, this is, in fact, not true. His trip to Tblisi was well-timed, as were his subsequent policy statements (in support of eventual Georgian NATO membership, not, as some have mistakenly argued, immediate inclusion).

Though the Conservative leader has been called an ambulance-chaser, the truth is he was right on Georgia even before the current crisis. Whilst Gordon Brown sat on the fence during the discussion of Georgia’s NATO membership at the Alliance’s Bucharest Summit, Cameron backed Tblisi’s bid in a thoughtful Chatham House speech a day before the summit. I would not be surprised if we saw more sojourns to the world’s hotspots, and as Coffee House’s own James Forsyth has pointed out, the Tory leader has already “developed relationships with pretty much every important world leader apart from Putin.”

But, as Coffee House readers will be quick to point out, such a focus carries risks too. People are no longer happy with the idea of Britain as an international mover-and-shaker, at least not if it costs money and – in people’s minds – makes them less safe. Until now, the Tories have tried to bridge these two impulses with a notion Cameron describe as “Liberal Conservatism”: liberal because it support the aim of spreading freedom and democracy, and supports humanitarian interventions; but conservative as it maintains a Burkean recognition of the complexities of human nature, and a healthy skepticism of societal re-engineering, especially if the reengineering is of other peoples’ societies. This comes very close to what Condi Rice called “American Realism”, a post-Iraq vision, informed by Teddy Roosevelt’s dictum: “power undirected by high purpose spells calamity, and high purpose by itself is utterly useless if the power to put it into effect is lacking.” But will this be both enough of a philosophy to guide Tory foreign policy whilst assuaging the concerns of many Tory voters? Take it away, folks. . . .

Comments