There’s one subject that you don’t raise with David Cameron’s circle if you want the conversation to last: the election result. They don’t like to be reminded that they failed to win a majority. The Cameroons have been persuading themselves that coalition government is the best possible result. No. 10 has been dubbed ‘the love nest’ by the rest of Whitehall. The Tories inside gush about their new Liberal Democrat colleagues.

But just next door, there is a man who is still obsessing about how to win a Tory majority. George Osborne has digested the election result, does not regard it as a success, and is seeking to learn from it how best to create a Tory parliamentary majority in this country again. He has been observing recently that Gordon Brown spent 13 years successfully creating Labour voters — mainly through state dependency — and that the Tories need to reverse this process if they are to win. It would also mean fostering a new set of Tory voters in the way that Margaret Thatcher did with council house sales and the ‘Tell Sid’ expansion of share ownership.

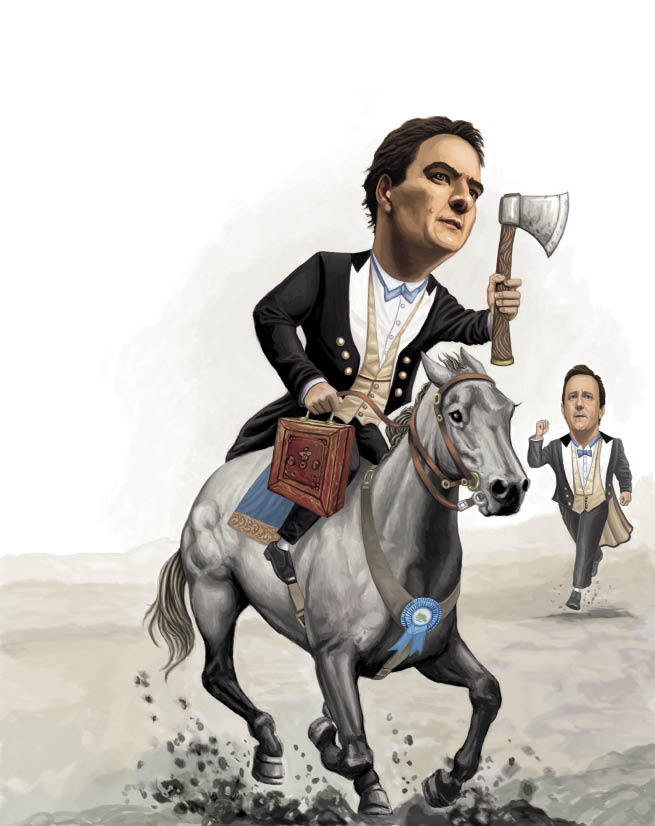

This is the strategy that underpins Osborne’s first Budget. The headlines were, predictably, about cuts. But this Budget can be seen as Osborne taking charge — in every respect. It is the first dramatic step in his plan for Britain. Osborne’s agenda is distinct from (but by no means hostile to) David Cameron’s. The aim is a majority Conservative government. If the plan succeeds, there’ll be no need to have the Lib Dems in government in five years’ time.

Mr Cameron and Mr Osborne have been so inextricably linked since their emergence on to the political scene that it is easy to think of them as one and the same. Osborne ran both Cameron’s leadership campaign and his general election campaign, and is godfather to his son Elwen. For years they have worked from adjoining offices and shared a staff — an arrangement they had hoped to keep going by knocking down the walls in No. 10 and No. 11 and running one big Downing Street office. But coalition put paid to that. Each needed to work with their Lib Dem deputies. Mr Osborne is now in the Treasury, slowly developing his own centre of political gravity.

Things are drifting back to the status quo ante. These two men come from different Conservative traditions. Osborne calls himself a ‘social and economic liberal’, not a label that Cameron would apply to himself. Osborne was the first to become a moderniser. It was Osborne who persuaded Cameron to take up cycling to work (although, typically, it is Cameron who became known for it). On foreign policy, Mr Cameron has half-jokingly referred to his Chancellor as a ‘neocon’ — but this is about as deep as their differences run. It is mostly a matter of style. Mr Osborne is a strategist, a man who wants to be thinking three moves further ahead than his opponent. That is why he is the only one of the pair who could have produced this Budget.

The mission, as Mr Osborne sees it, is to shrink the public sector and grow the private sector — the classic goal of the modern British centre-right. The Budget is ambitious on this front. It will reduce the state’s share of the economy to below 40 per cent by the end of this parliament, reversing the rise of the state under Labour. Shirley Letwin argued that the Thatcher government unleashed ‘vigorous virtues’ through its reforms. According to her, Thatcher transformed the country and society by rewarding the strivers and anyone who was serious about self-improvement. This is what Mr Brown eroded, not just by employing 700,000 more voters but by offering low-level welfare to millions.

Tax credits is a classic example. During the election campaign, nearly every Tory candidate despaired at how so many families on £50,000 a year were voting Labour to protect their £545 child tax credit — despite the overall cost of a Labour government to them being far higher than that. Osborne’s Budget dealt with this directly. Within two years, no family earning £30,000 a year or more and with one child will receive tax credits. That class of wavering Labour voters, so irritatingly prevalent in marginal seats, will be no more.

Labour may well pledge to restore the tax credits. But they’d also have to explain how they’ll pay for it — and Osborne plans to make sure that they do. In the same way that Brown and Balls translated every proposed Tory tax cut into the number of nurses and teachers that would have to be laid off to fund it, the Tories will claim that every Labour move will lead to a rise in tax. It will become the Tories’ dividing line and be as endlessly repeated as investment versus cuts was. And the fear of losing something one has — which, in the election, was tax credits — is more potent than being promised a tax break by a politician at campaign time.

Tellingly, the Budget said there’ll be no more reductions in government capital spending. This will have two effects. First, it means that spending on the infrastructure which business needs will continue — making Britain a more attractive place to invest and helping the private sector to grow. Second, the axe will now fall even more heavily on current spending in the public sector. This will lead to a significant shrinkage in the army of public sector workers, a group with whom the Tories failed to make much progress at the last election.

Opportunities for those leaving the public sector will, in Mr Osborne’s economic chess game, come from companies lured here by what will be the lowest rate of corporation tax in any major western economy. The Chancellor is taken with the Irish experience, which shows that setting out in advance plans to reduce corporation tax leads to companies investing even before the lower rate kicks in. Just as the delayed VAT cut is designed to push forward new spending, so the pre-announced corporation tax cut is intended to lure businesses here today.

The sculpting of a new Tory nation does not end there. Osborne has also noticed how Tory votes fall away the further north one travels. Both Scotland and the north of England have levels of state spending which exceed that of some Warsaw Pact countries in the Soviet era. Rather than try to build a new silicon valley, Mr Osborne is offering a tax break to anyone who sets up a new business in the most state-dependent regions of the country. The aim is to encourage enclaves of entrepreneurship, breeding Shirley Letwin’s ‘vigorous virtues’ and voters receptive to Tory messages

The Tories hope to woo those workers who remain in the public sector with their offer to allow them to stage management buy-outs of the services they provide — and keep any savings they make as profit. These new groups may still technically be in the public sector. But they would believe that their working arrangements depended on a Tory government.

Then there are the parents. The plan by Michael Gove, an Osborne ally, to allow teachers, parents and voluntary groups to set up state-funded schools also has the potential to reap an electoral dividend. The Labour leadership contenders have all declared that they will vote against the legislation to enable so-called ‘free schools’. So did the Swedish social democrats when the Swedish Conservatives introduced their system in 1993. But once the genie of choice is out of the bottle, it is a brave socialist who tries to stuff it back in. Parents who send their children to these schools will have reason and motivation to vote Tory as long as Labour opposes them.

All through the Budget, you can see Osborne’s plans to make new little Tories. His plan to allow people to buy discounted shares in the nationalised banks when they are sold, for example, was ridiculed by Vince Cable when it was first announced. But it would change the terms of debate about the banking industry. Osborne has long assured private meetings of bankers that he is looking for a way to move politics away from banker-bashing. To have swaths of the public own shares in the banks would be to create a breed of voters who invested in their success.

Osborne’s friends describe him as a pragmatist about the coalition. They say that he regards it as a relationship of convenience, not a love match. Those Tories who are interested in a takeover but not a merger with the Lib Dems are coming to view Osborne as their protector.

He is also developing more of his own political identity now that he’s not sharing offices with Cameron. When one senior Tory backbencher went to see the Chancellor recently, he was surprised that he constantly referred to the Prime Minister as ‘Cameron’. In opposition, it was first-name terms. Cameron and Osborne do, however, remain remarkably close. They worked on this Budget together — but generally with Nick Clegg and Danny Alexander in the room. Cameron apparently fears that Clegg will feel sidelined if he and Osborne spend too much time alone together.

There used to be a fair amount of grumbling about Osborne among Tory backbenchers. But now many are coming to see him as the man who’ll ensure that the Tories get the better deal out of the coalition. In the days after the coalition was formed, it was Osborne who called round explaining why it was a good deal for Conservatives of all stripes. The arrival of the new intake also means that there are now a substantial number of Osborne loyalists on the backbenches: the handwritten notes he has sent out over the past few years have had the desired effect.

In his dealings with Tory MPs, Osborne has consistently argued that the real prize that the coalition offers is cover on the cuts. And he is using this cover to create an electorate that is more likely to deliver a Tory majority in future. During the coalition negotiations, he told Tories who were jittery about governing with the Liberal Democrats that only from inside government could the Tories tilt the country in their direction. The argument was that the coalition was a necessary stepping stone on the way to a Tory majority. To him, that has always been the prize.

There will be some who scoff at the idea of Osborne having a plan. They’ll contend that it was precisely his too-clever-by-half ideas that cost the Tories an outright majority in the election, and that he has forfeited all claim to be regarded as a strategic genius.

But the end result could be an even greater triumph: Osborne won Lib Dem support for a Budget which is intended to enable the election of a Tory majority government next time around. This Budget will certainly lead to a far smaller public sector. The corporation tax cuts should have created a far larger private sector by the time of the next election.

Michelangelo said that he saw the angel in the marble and carved until he set him free. Osborne has seen how the coalition can produce a Tory majority and will chip away until he achieves it.

Comments