So the IMF has revised its forecasts for the UK’s GDP growth downwards — to 0.2 in 2012 and 1.4 in 2013 from the 0.8 per cent and 2.0 respectively it predicted in April. It’s bad news, certainly — not least because we’ve been downgraded more than most other countries, and we’re now forecast to grow more slowly than Germany and (this year) France. But it’s worth bearing in mind that the IMF — for all its ability to drive headlines — is just one of many organisations playing the forecasting game, and these downgrades actually just bring them into line with the average.

What’s worrying for George Osborne — and his fiscal consolidation programme — is that the average is moving further and further below the OBR’s growth forecasts, upon which all of the public finance predictions are made. This means that, unless things change for the better in the next few months, we can expect yet another downgrade in November — a gloomy backdrop for Osborne’s autumn statement.

If the OBR lowers its forecasts, there will be big knock-on effects for the public finances — and that all-important commodity: credibility. Pete laid out the danger ina prescient Times column last year, but it’s a warning worth repeating now.

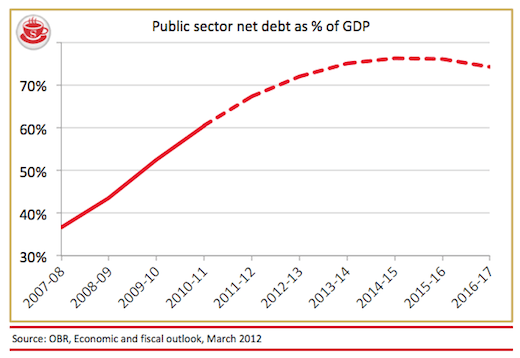

Osborne’s currently just on target to meet the two fiscal rules he set on becoming Chancellor: to balance the cyclically-adjusted current budget (aka ‘eliminate the structural deficit’) by the end of a rolling five-year period, and to see public sector net debt falling as a share of GDP in 2015-16. The first of these may withstand a growth-downgrade, as the ‘rolling’ nature of the period means that the deadline is extended every year. So whereas in March the forecasts had to show the structural deficit eliminated by 2016-17, in November it will only have to show it being eliminated by 2017-18. The second target, on the other hand, has no such in-built leeway. At the moment, as the graph below shows, debt is predicted to peak at 76.3 per cent of GDP in 2014-15 and drop ever-so-slightly to 76.0 per cent in 2015-16. But lower growth forecasts could well transform that small drop into a small rise, and turn a target met into a target missed.

Osborne has responded to previous growth downgrades by letting borrowing rise, while staying (just) on track to meet his targets. But next time, he may not have the luxury. If that does transpire, Osborne will have to make what Pete called ‘a hideous choice’: let the debt continue to rise and risk the UK losing its AAA credit rating or go for faster deficit reduction (meaning more cuts and more tax rises). It’s not a choice that an already unpopular Chancellor, with the next election already beginning to loom large, wants to be faced with.

Comments