Earlier this year, officials in the Indian driving licence department received an extraordinary application. It was from Lakshmi Mittal, the richest man in Britain, who wanted to know — given the circumstances — if it would possible for him to be posted the documentation rather than sit a driving test. They refused, and the steel magnate duly turned up for his fingerprints a few days later. The Indian press were delighted, and not just to see a billionaire humbled. A driving licence application looked very much like the first step back to residency. India’s richest exile might just be the latest to flee London.

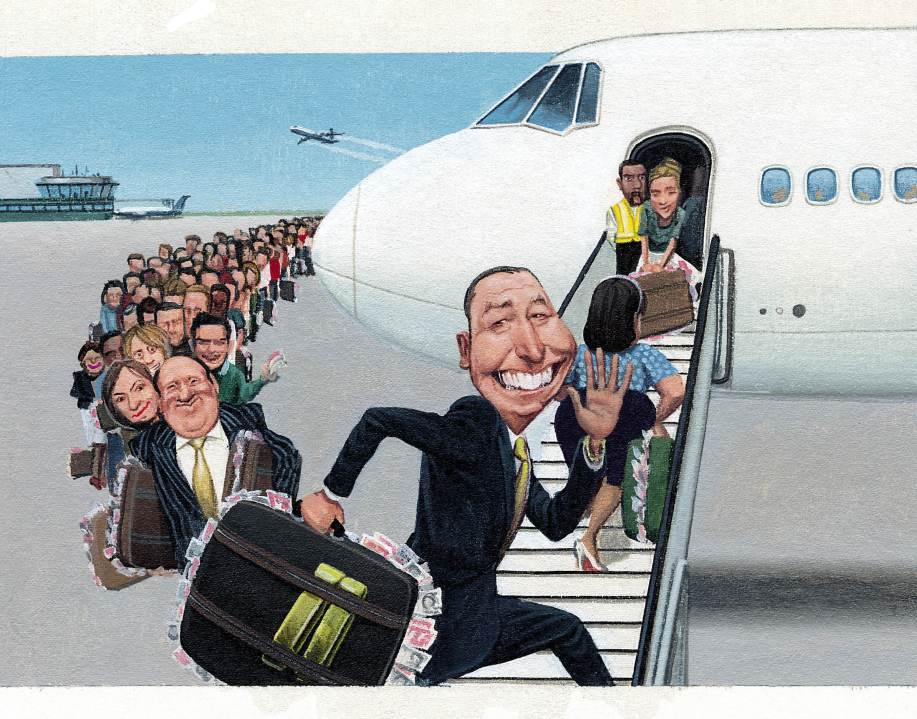

If he did, it would be a symptom of what could be a much wider problem. For two decades, Britain has had a low-ish top rate of tax — 40 per cent — which has attracted entrepreneurs the world over. But then the crash came, and the mood changed — Britain now has the fourth highest top rate of income tax on the planet. George Osborne has combined the 50p rate with a series of new levies on banks, and dark talk about how the rich must pay a ‘fair share’. All this has persuaded a good many financiers that Britain has, finally, decided to take a carving knife to the golden geese. One by one, they are flying away.

Many will say good riddance to bankers, but the hole they leave in Britain’s finances is remarkable. As a country, we are strikingly reliant on a small number of highly mobile financiers. The best-paid one per cent, for example, contribute a quarter of all income tax collected — a figure which ought to warm the heart of the most ardent redistributionist. But the popular conception is that the richest pay almost nothing, and should be clobbered. Britain has become one of the three countries in the world (along with Greece and Iceland) to put up the tax rate sharply — and see what happens.

The squeals are seldom audible. The likes of Mittal enter or leave Britain without fanfare or protest. It was the artist, Tracey Emin, who declared that she was ‘simply not willing to pay tax at 50 per cent’, and added that she might emigrate. The actor Sir Michael Caine put it even more bluntly. ‘We’ve got 3.5 million layabouts on benefits, and I’m 76 years old, getting up at 6 a.m. to go to work to keep them,’ he said. Both were denounced in the press: the popular mood is for eating, not just squeezing, the rich.

So the bankers know better than to howl. They talk quietly, as the banks reporting profits did this week, about evaluating whether it’s worth moving headquarters and declaring tax elsewhere. And instead of creating jobs in Britain, they do so in one of their many worldwide offices — or send staff to work in lower-tax jurisdictions. HSBC has already made noises about moving its headquarters abroad. There is excited talk in Wall St about luring Barclays HQ from under the nose of David Cameron — an idea which is being taken seriously by the company’s board.

These are not idle threats. The hedge fund industry — perhaps the biggest employer of high taxpayers in Britain — is midway through what can only be described as an exodus. One in four fund managers has moved to Switzerland, according to a study by Kinetic Partners, at an awesome cost to the British taxpayer. The departure of two industry magnates and their staff — Alan Howard, founder of Brevan Howard and Mike Platt, of BlueCrest Capital — is expected to yield £200 million a year less in taxation. All told, about 1,000 hedge fund managers are thought to have decided to move from London to Switzerland — where the top tax rate, incidentally, can fall as low as 12.3 per cent.

But no tally is kept on the rich, no exit visas are made. There is a list of companies who have moved their head office out of Britain (United Business Media, WPP, Shire, McDonald’s, Kraft, Procter & Gamble), but the broader picture is captured from fragments, snapshots from overseas papers. The Swiss press runs stories about Les Traders Anglais — but the people in the pictures are often Japanese, American and French who had been working in London. ‘Osborne says how various bankers tell him they’ll never leave Britain,’ says one financier who has discussed the issue with the Chancellor. ‘But he’s being advised by Brits, who have kids in English schools. The people we’re losing are foreigners — people who uprooted their lives to come here, and will go away just as easily.’

In the absence of any census on the rich, the Sunday Times Rich List can be used as a rough proxy. When it first started in 1988, just 11 per cent of its members were immigrants. Now it is 40 per cent. The City has become a magnet for the world’s talent, but the newcomers have no spokesman or trade union. And while Mr Osborne has declared his intention to cut corporation tax, many companies can’t wait. Wolseley, the world’s largest plumbing and building supplies firm, recently said it would move to Switzerland to ‘achieve a competitive effective corporate tax rate’. This is, of course, never the full story: businesses say they tend to look at the overall mood music. And the message here is decidedly mixed.

There is not much defence of capitalism in Britain. Instead we have a Business Secretary, Vince Cable, who mutters darkly about how ‘capitalism takes no prisoners, and kills competition where it can’. Even the Chancellor inserted a banker-bashing passage in his latest budget speech. When taken to task by a Conservative MP afterwards, Mr Osborne replied that his words were nothing compared with what’s being said on the Continent. The MP left with the depressing impression that Mr Osborne believes that his main competition is in Europe, when the banks are piling into Southeast Asia.

The story of the British finance sector migrating eastwards is, again, told only in clippings from foreign newspapers. The London-based Standard Chartered told the Chinese press last week that it was expanding its operations there by 40 per cent. The head of its Southeast Asia division, Ray Ferguson, declared on Tuesday that he’d relinquished his British passport and taken up Singaporean citizenship. These are not decisions one takes in a fit of pique. A debate was recently organised near the Chinese embassy entitled ‘Is Shanghai the new London?’ It was cancelled, due to a strike on the London Underground.

It is unfair to say that the Chancellor’s economic strategy is backfiring, because this is not his strategy. The 50p tax was a trap set for him by Gordon Brown, who is economically literate enough to know that this was an act of fiscal vandalism (and delayed implementing it until his last month in office). But he also calculated that Mr Cameron and Mr Osborne are so sensitive about their privileged background that they would not dare to oppose it lest they were accused of pandering to the rich. Mr Osborne embraced it, saying it would make the cuts more palatable.

Even Vince Cable admits the tax will probably not raise money. But there have been pitifully few attempts to calculated was the extent of the damage. The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates that the 50p rate would mean, overall, about £800 million less revenue — but it was assumed that the high-paid are no more mobile than they were in 1988. A study, conducted by the TaxPayers Alliance for The Spectator, suggests the amount lost would be close to £4.5 billion this year — on conservative estimates. This study assumes that, for every £1 raised by the tax, £1.80 will be lost by people who either leave, hire better accountants, or cancel plans to move to Britain. Companies grumble that it is harder than ever to persuade overseas staff to come to the UK. A Gallup poll this week, asking people around the world where they would most want to immigrate, ranked Britain below New Zealand, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia. All this suggests the 50p tax may well be the single most costly government policy.

Almost all Western countries face a deficit problem, but the majority have been cutting rather than raising the top tax rate — seeing this as the most effective way of extracting money from the super-rich. Britain is one of a handful of countries that have moved the other way, along with Iceland and Greece. It is seldom the sign of a country planning for the long term.

The tragedy is that Mr Osborne is indeed planning for the long term. His banker-bashing is tactical, his proposed corporation tax cut is real, and he can plausibly claim to be a low-tax Tory trying to sell a radical package of cuts without triggering Greek-style riots. It is a question of balance. So far, he has been remarkably successful in gathering public support for the cuts. One can argue that an electorate about to face a VAT rise is in no mood to hear about the Laffer curve. The problem is that no one, anywhere, is asking whether there might have been ways to tax the rich that actually raises revenue.

Years before Arthur Laffer doodled his now-famous tax yield curve on a cocktail napkin, John F. Kennedy was explaining the point of low-tax economics to Americans. ‘It is a paradoxical truth that the soundest way to raise the revenues in the long run is to cut the rates now,’ he said in 1962. This is backed up by various economic equations, elasticity ratios and the experience of the 36 countries who have cut the top tax rate in recent years. Yet the intellectual climate in Britain is such that no one is making this basic argument in public now.

Well, almost no one. Defending himself on radio, Camberwell’s most famous son put it this way. ‘I left for eight years when tax was put up to 82 per cent. The newspapers said: “Michael Caine’s leaving: let him go, the stupid, overpaid, loudmouth idiot, who cares where he goes?” Well, you didn’t get 82 per cent tax from me for eight years and a quarter of a billion dollars worth of movies were made outside this country instead of inside it. Now, that is just from one stupid, loudmouth moronic actor. Imagine what happens with companies that disappear.’

Mr Osborne need not imagine. If he looks carefully enough, it is happening right before his eyes.

Comments