Desmond Shawe-Taylor, Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, on a radio programme that tells the history of the monarchy through 50 objects in the Royal Collection

A History of the World in 100 Objects managed to squeeze the great paradigm shifts of anthropology into the interval between the roadworks sign and the all-clear, spiriting away traffic cones with remote customs and belief systems. What could follow something so confidently global if not an examination of our own strange customs and belief systems — some introspective anthropology? The Art of Monarchy, though a history told through 50 objects in a single collection, is not intended as another History of the World, but the comparison allows us to imagine how our material–cultural footprint might be interpreted by some remote and future museum. The guide through the material, the BBC’s arts editor Will Gompertz, catches the amiable but probing bemusement that such a remote viewpoint might provoke. He examines a range of objects and asks a range of people (most of them subjects) about a millennium of royal history.

Finding the objects was easy: the Royal Collection contains the accumulated treasure-trove of the British monarchy, the carefully conceived engines of magnificence and the incidental evidence of momentous events. Making the selection proved much more difficult as it required us curators to look beyond intrinsic quality; somebody should do a ‘hundred masterpieces that changed the world’ but this was not it. What made the process more taxing was that the information that a museum curator supplies as a matter of course — what the object’s use was and what it tells us about its users (in short, its anthropology) — is not something consciously considered when the object in question is still in use.

Queen Elizabeth II signed her coronation oath using a 1953 Sydney Cockerell pen; she went to the Abbey in the 1762 State Coach; the anointing took place using a 12th-century coronation spoon. We all know roughly what a coronation is, but what is the precise character, history and significance of this ceremony? These insights are harder to find, especially now that ‘Kings and Queens’ has become a shorthand for everything which is not generally taught in school history.

If these objects are the tools of the trade, what exactly is the trade? What do monarchs do? The answer presented by this series suggests that monarchs (in no particular order) strut, fight, worship, encourage, preserve and occasionally try to live a normal life. Monarchs need to show off to awe their subjects and their rivals but also to provide the nation’s ‘Sunday best’ towards which subjects may turn with pride. Monarchs need to fight and to persuade others to do so on their behalf (an activity that also involves a certain amount of strutting).

The sovereign is the supreme governor of the Church of England and was, at least until the Civil War, considered to be part of the great chain of being, linking divine and human life. Monarchs instigate activities that benefit the nation and humanity — academies, industries and charities. Monarchs personify continuity of things and institutions; the person who made Edward III’s monster ‘bearing sword’ has the same job title (Royal Armourer) as the one who now advises on its conservation.

Much of a monarch’s ‘normal’ life was subsumed into the duties set out above: while we might get up in the morning; a monarch had a levee. Sometimes, however, especially after the accession of Queen Victoria, a private life became possible, though more often than not our record of it is crafted with half an eye to public consumption. The monarchy is also the mirror in which people see themselves and the Royal Collection holds these innumerable insights into two relevant population groups: the British and the citizens of the Commonwealth.

All these things leave an extraordinary range of objects in their wake. Some are precious — the sword and scabbard presented to Edward VII at his coronation by the Maharaja of Jaipur carries 719 diamonds. Some have what is called ‘sentimental value’, like the shard of George Washington’s coffin also given to Edward VII, though while Prince of Wales, during his 1860 visit to the United States of America.

Many have a significance which is exactly the opposite of their ‘face value’. The magnificent silver-gilt ‘Salt’ dispenser was given to the restored Charles II in 1661 by the City of Exeter as a token of their loyalty precisely because they had been disloyal during the Civil War. Henry VIII’s 1521 treatise on the then much disputed matter of the Seven Sacraments earned him the title of ‘Defender of a Faith’ which he devoted the rest of his life to attacking.

Other objects offer similarly poor prognostication. The photograph of a Chartist meeting at Kennington in 1848 records a movement which was believed to threaten the very foundations of the British monarchy; the photograph of the ‘Grandmother of Europe’, at a family gathering in Coburg in 1894, includes three first cousins —

the future Edward VII, Tsar Nicholas II and Kaiser Wilhelm II — who were supposed to turn Europe into one great big ‘family group’.

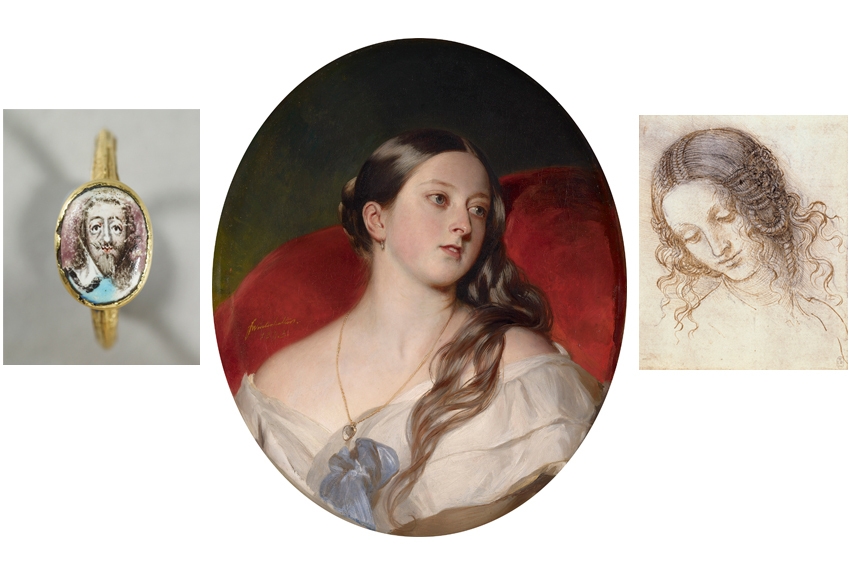

Both these photographs pose the question why did 1789, 1848 and 1914 not do for King or Queen what they did for Roi, Kaiser and Tsar? Any one of these programmes makes clear that this question invites a comparison of oranges and pears. However remotely it might on occasions have lived, the British monarchy got itself locked into a close and reciprocal contractual relationship with the British people from the outset. The Magna Carta is almost as old as the Coronation Spoon. A memorial ring with a miniature of Charles I on the outside and a skull on the inside was one of a type given by Queen Henrietta Maria to her husband’s supporters as a token of their loyalty (to be redeemed in the event of a restoration). The ‘Formulary’ of the coronation service for King William III and Queen Mary on 11 April 1689 sets down the Oath, which includes the phrase ‘according to the Statutes in Parliament agreed upon’ and further requires the monarchs to profess the ‘Protestant Reformed Religion established by Law’. The Stuarts fought the Law and the Law won. Whether this closeness is ‘head-to-head’ or ‘shoulder-to-shoulder’ depends upon the era and the historian describing it. This is something distinctively British, but not exclusively so: in the exchange between Haemon and Creon in Antigone Euripides suggests that by themselves kings are fit only to rule desert islands; the Dutch Revolt of 1568 perhaps formed as crucial a part of the story of the foundation of the British Constitution as John Hampden’s refusal to pay ship money.

In general, though, over the years the British monarchy has bent more and broken less than others. There may be other possible reasons for its survival: royalty used to sit at the top of an aristocratic pyramid (an arrangement captured in the unique illustration of the opening of Parliament of 1523, which appears in the Wriothesley Garter Book); now its most obvious context (discounting the immediate ones of court, Church and armed services) is the charitable sector. Working with philanthropists and volunteers probably seems to most people like keeping good company.

The first programme, Behind the Royal Image, in the eight-part series The Art of Monarchy, a collaboration between the Royal Collection and BBC Radio 4, is on 11 February at 10.30 a.m.

Comments