Charlie Taylor has narrated this article for you to listen to.

Just as the drama of the escape and recapture of Daniel Khalife settled down, HMP Wandsworth returned to more routine problems. On Sunday, another prisoner was hospitalised, having been stabbed by a fellow inmate.

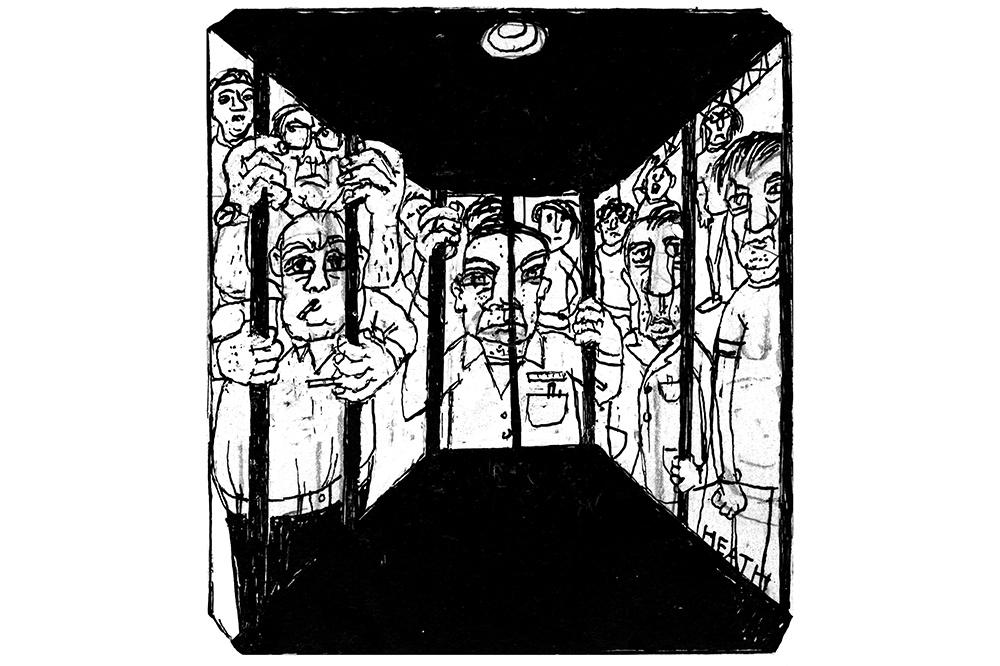

Quality of staff is critical. The best officers have an intuitive sense that something is going on

This sort of violence is all too common, especially in the overcrowded Victorian local prisons that hold often volatile remand prisoners. In the past year there have been 1,878 serious assaults on prisoners, an increase of 32 per cent on the previous 12 months. The cause is usually a score being settled between gangs or the failure to pay a debt.

There is big money to be made getting drugs and mobile phones into prisons – and since Covid restrictions were finally lifted, the availability of drugs has shot back up. Although the levels are not yet what they were before the pandemic, our recent inspection at the high-security Woodhill prison near Milton Keynes revealed that in a random drugs test, 38 per cent of prisoners tested positive. Most prisons now have better systems for disrupting drugs supplies, but the staff are up against organised crime gangs who find ingenious ways to break through – and drugs lead to the kind of debt that can end in retributive violence.

Escapes such as Khalife’s are very rare. In my three years as chief inspector, only one other inmate has managed to get away – by slipping out of the visits hall while staff were distracted. That previous incident had nothing like the profile of last week’s case because the man was in for a more mundane offence and quickly recaptured. Prisoners occasionally abscond from open prisons, but far less than in the past.

What happens surprisingly often is accidental releases – 71 last year, up from 54 the year before. These normally involve a failure in the bureaucracy whereby a prisoner with an outstanding arrest warrant is allowed to leave at the end of his or her sentence or because the court grants bail without anyone realising that he or she is facing other charges. Most are caught again, but some serious offenders have managed to get away.

Security for breakouts from prisons generally works well because there are clear routines to follow, such as searching on top and under departing vehicles – but also because the systems avoid a single point of failure. If someone leaves a gate open, other layers of security will prevent an escape.

Governors regularly test their own systems, too, by asking a member of staff to try and get out of the jail without either ID or keys. Even if they manage to get through a couple of gates, they usually get picked up before they leave the prison.

The quality of staff is critical. The best officers have an intuitive sense that something is going on. Too often, though, very young staff look after prisoners who have been inside longer than the officers have been alive.

A common frustration of governors is the quality of new recruits. Astonishingly, governors play no part in selection, meeting new officers only on their first day at work. They say that they can tell within minutes which officers are not going to cut it. Yet removing an employee can involve protracted HR exercises.

The bureaucratic stranglehold is stifling. One governor told me recently that to buy a pot of paint she had to go through a lengthy procurement process, rather than send someone to the nearest B&Q. Indeed, governors spend more time wrangling with contractors for basic repairs or getting education and health providers to do their job than they do going round the jail. Inevitably standards slip.

At Ford open prison, I noticed that the football pitch was in unexpectedly pristine condition. I was told that prisoners could only play when supervised by officers, in case they hurt themselves; and that at the moment the prison was short-staffed, hence no football. After three meetings with prison service officials, we finally got them to agree to running an unsupervised football trial at Ford – a rare, if small, triumph.

With these constraints, it is hardly surprising that the turnover of governors in some jails is high. There are often very few applicants to govern the most difficult inner-city prisons. One governor said to me: ‘At times I feel more like a contract manager than a leader.’ If this is what the job has become, then we will end up with people who like managing contracts rather than inspirational leaders such as Pia Sinha, who turned HMP Liverpool around, or Ian Blakeman, who has done a remarkable job at Pentonville. And the less impressive our governors are, the more violent and disorderly our prisons will become.

Khalife may well be the last escapee during my tenure as chief inspector. Sadly, the stabbings will continue.

Comments