Our ruined attention spans seem to be the consequence of a recent fall from grace. Big Tech was our tempter. Having tasted its dopamine, we got hooked on its likes and notifications.

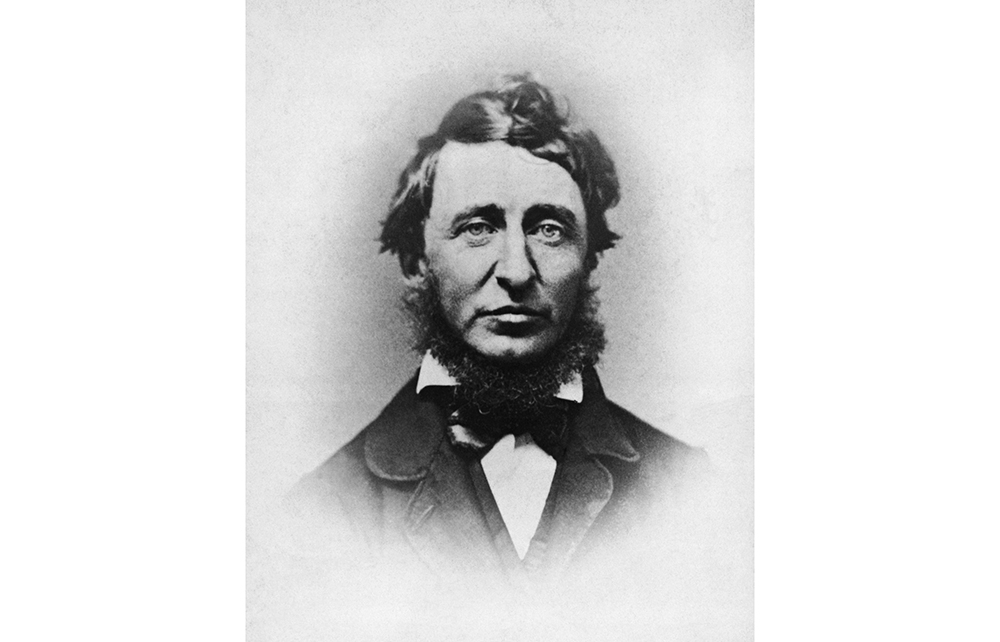

Even Thoreau got bored with practising his ‘habit of attention’ at Walden Pond

But while the digital attention economy is new, the struggle to concentrate is not. Caleb Smith’s elegant anthology of American anxieties over attention begins with the perplexities of Henry David Thoreau in early19th-century England. Believing that the ‘mind can be permanently profaned by attending to trivial things’ and that a commercial age allowed ‘no sabbath’ for our thoughts, Thoreau fled Boston for a shack on the quiet borders of Walden Pond. But he found distraction lurking even there: the fish in its depths were disturbed by the rumble of passing trains.

Because a physical escape from modernity was impossible, it was vital to rise above its harmful buzz. Alongside Thoreau, Smith introduces us to a host of his contemporaries, both famous (Herman Melville, Frederick Douglass and Emily Dickinson) and obscure, who were united by a fear of losing their minds. In crisp but plangent meditations on brief passages from their writings, he shows how they tried to still the clamour of the world by attending to it in calmer and more disciplined ways.

These anxious souls seem to resemble us in their yearning to live in the moment, even if they never had to hide a Twitter password or shut up smartphones in a drawer. Yet these appearances are deceptive. This ‘genealogy of distraction’ is instructive precisely because its figures had different, perhaps deeper, worries than ours.

Smith, whose upbringing in evangelical Arkansas acquainted him with the strange joys and baleful power of American Protestantism, is wonderfully sensitive to its social and psychic hold over 19th-century life. Americans once fretted about waning powers of concentration mainly because they yearned to ‘attend upon the Lord without distraction’. He dwells on the lurid sermons of clergymen because their dread of Satan’s wiles generated insights into the distracting magic of cheap print. While many of them were concerned only with the plight of white minds, Smith’s book also highlights the numerous black Christians who vindicated, against racist scepticism, the ability of all people to pursue education, concentration and salvation.

In a deeply Christian culture, even people who had left that faith behind wrote about powers of mind in religious ways. When William James suggested how a distracted brain escapes the ‘shell of lethargy that wraps our state about’ and returns to the world because ‘an energy is given, something – we know not what’, he described an infusion of grace in the language of psychology. When Walt Whitman asserted in Leaves of Grass that ‘the scent of these arm-pits is aroma finer than prayer’, he shocked the prudery of his time, but was still writing in what now seems an embarrassingly devotional mode. His manly stink made the case that our bodies are the vehicles of, rather than obstacles to, our exaltation.

Yet Whitman and Thoreau were unusual in being free spirits. The obsession with mental rehabilitation was more often a symptom not of individual liberty but its absence. Smith, who has taught literature to prisoners as well as to Yale students, is all too aware that disciplines of intention appealed to penitentiaries and juvenile reformatories as a means of turning unruly souls into single-minded workers. Middle-class revivalists likewise urged their hearers to become ‘business Christians’, who studied their accounts as carefully as their Bibles. On the other hand, the institution of slavery scrambled the moral parameters of attention: for enslaved people, daydreaming was a kind of muted resistance, which their demonic overseers sought to extinguish through incessant watchfulness.

Any reader of Foucault will find this emphasis on the pervasive psychic manipulation of people by institutions depressingly familiar. But Smith evokes the volatility of individual minds in this fallen world with a pathos and wit lacking in his theoretical influences. He feels, above all, that we can still learn from a past he has taught us to find strange. We cannot solve our misgivings about our disintegrating present by fine tuning how we feel or think about it, just as the purist regimens of Smith’s reformers were no answer to the ravages of industrialisation. Even Thoreau, a patron saint of modern mindfulness, got bored with practising his ‘habit of attention’ at Walden Pond. His performative gazing at trees and rocks was a ‘constant strain’ on his senses, leaving him to yearn for a ‘true sauntering’ of eye and mind.

This gloomy yet humane book shows why a preoccupation with our mental hygiene can be a consolation, but also a trap. There are worse things in the world than losing our focus.

Comments