One of the saddest parts of a bookseller’s job is telling a customer that the book they want is out of print. This book is obviously very dear to them; more often than not they want a duplicate copy to give away to a friend or loved one. The eager, excited look in their eyes turns to disbelief, followed by slow grim acceptance, and then there’s the gradual setting in of mournful gloom.

Even if I offer to try to track down a second-hand copy, they often still find it hard to come to terms with the fact that this book – so dearly loved by them – wasn’t loved enough by its publishers to keep it in print. Indeed, it’s very sad to think that a book which, over the years, has blossomed in someone’s mind is now – to all intents and purposes – dead to the wider world.

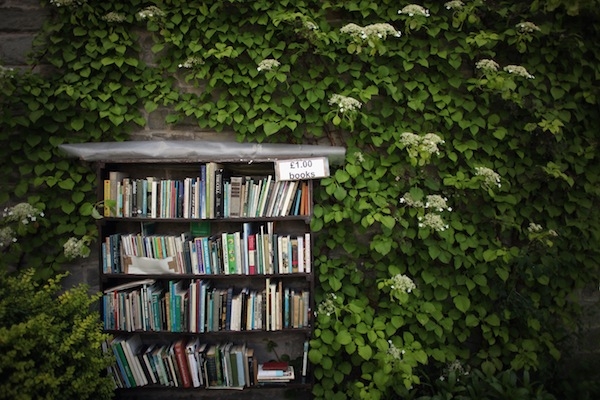

This sort of miserable encounter seems to be happening more and more often. So many new books are being published that booksellers are endlessly trying to make more space for new titles – usually at the expense of older books, which haven’t sold for a while. Once a book has stopped selling, it isn’t long before it falls out of print.

Publishers print books in editions of a few – or, sometimes, several – thousand. While a book is selling well, if a publisher runs out of stock, he or she will happily print another few thousand copies. But once sales have slowed to an unreliable drip – once this book has drifted out of readers’ consciousness – thanks to no more publicity, no more word-of-mouth recommendations, no more space on the bookshop shelves, then publishers are reluctant to take the financial risk of printing however many thousand more.

It’s much easier for the publisher to cross that one off the list and turn instead to the new books coming up, the ones which have the promise of reviews, of getting into promotions, of taking off rather than slowing down. Readers too have an insatiable appetite for the new, the next big thing, caring much less for a novel written a few years ago than one that’s fresh off the press, which all their friends are reading.

Inevitably, as so much is published these days, not all of it is of a brilliantly high standard. If a book is only so-so and falls out of print after a few years, then perhaps that’s not such a bad thing. It’s had its time and now it can bow out and make way for the next.

But these out-of-print books that people ask for aren’t only so-so. These books are special – at least they are to these people, who are longing for another copy years later. If a book can lodge itself so firmly into someone’s mind, then surely it must be good.

So we are very lucky to have a scattering of small, independent publishers, who love nothing more than to sift through these dead out-of-print books. Out of the ashes, they pick out flecks of gold, finding books that they believe are too good to let disappear. Capuchin Classics, for instance, republishes ‘books to keep alive’, such as forgotten Nancy Mitfords, GK Chesterton’s The Napoleon of Notting Hill, and O Henry’s The Gift of the Magi. Persephone Books looks mostly for neglected mid-century women’s fiction, which it publishes with plain grey covers and beautiful endpapers. And Dalkey Archive Press keeps an eye out for subversive books, also seeking to turn our Anglo-American-biased eyes towards more translated fiction, which currently makes up only a measly 3 per cent of the UK’s annual literary publishing output.

These independent presses put a great deal of thought, care and effort into republishing these lost gems. They genuinely love the books they rescue from obscurity and long to make this new life of the book a good one. They give them smart new covers; they gather disparate titles into a series – thus making them seem more substantial; and they drum up as much publicity as they can possibly muster. It means that rather than an old title malingering on a dusty shelf, overlooked by shoppers who can’t see past the piles of new bestsellers, these books reappear with a little fanfare, certainly not with the toll of the funeral bell.

Perhaps, then, it doesn’t matter if the big commercial publishers let their old books fall out of print so quickly, so long as there’s a loving little press to bring the good ones back to life. But let’s not forget that these little presses don’t publish the bestsellers of the big commercial houses. They don’t have those hits to swell their finances, and are often not much more than a tiny operation, with staff motivated more by a belief in doing something important than bulging pay checks. Surely they should be rewarded for doing us such an excellent service. Patrons and benefactors please look this way! And for the rest of us, let’s pay a bit more attention to these old books deemed worthy of a new lease of life. Certainly, for each sad customer whose heart has leapt with joy at the realisation that someone else has discovered and resuscitated a favourite lost book, I’d like to say thank you very much indeed.

Emily Rhodes tweets @emilybooksblog and blogs at Emily Books

Comments