Cricket writing, in the age of professionalism, affords less room to dreamy scribes. Fact and revelation are preferred to style and reflection. The roaming tour diary is rare, ghosted autobiographies rife. There are notable exceptions, of course, and we can happily toss Duncan Hamilton among them.

Hamilton is on a roll. He has won the William Hill Sports Book of the Year twice, in 2007 and 2009, the latter for his biography of Harold Larwood, chief executioner — and victim — of the infamous Bodyline tactic used to nullify Don Bradman’s Australians in 1932-33. The Larwood book cracks along at a hurtling pace; A Last English Summer, set to the beat of the 2009 season, is a much more personal and contemplative read, which escapes woolly romanticism by the style of its delivery, every bit as crisp as the sound of a new leather ball on a willow bat.

Each chapter takes Hamilton to another setting, from Lord’s to Acre Bottom, home of the Lancashire League club, Ramsbottom. His eyes are sometimes on the cricket, sometimes gazing to the uncertain future, sometimes straining to see the scene of eras gone. Present merges with past. Is that the Sri Lankan Angelo Mathews, performing a piece of unimaginable fielding on the Trent Bridge boundary, or W. G. Grace, posing for a photo with the England XI in what would be his last Test match?

Neville Cardus himself is accused of sentimentality, and at times Hamilton sails close to the wind. The prose is unashamedly rich, calling upon those writers — R. C. Robertson-Glasgow, John Arlott, J. M. Kilburn and Alan Ross — whose spirits course through this book. Literary references abound, from Shakespeare to Chekhov to Beckett. Certainly you will need to accept that cricket is more than a game of bat and ball. Which it is, of course.

Hamilton hasn’t chosen any old time to take cricket’s pulse: like many he senses ‘the traditional weave of the game was being unpicked and rearranged for the modern, global age’. The new, popular and profitable Twenty20 format is sucking administrators, players and spectators away from the modest traditions of yesteryear. But the author does well to remember that cricket is perpetually ‘in crisis’, yet seems to get by in the end.

Nevertheless, the threat of Twenty20 blows through these pages like a winter chill. It isn’t just because its hurried character surrenders to instant gratification; the silly gimmicks and blaring music are the real bandits for Hamilton. Yet the game of Twenty20 has merit even for the purist. Players learn extraordinary skills to cope under the extreme conditions, as Hamilton witnesses at Trent Bridge, when Mathews demonstrates ‘the unbelievable lightness of fielding’.

No, the problem is less the game itself, or even the bright lights. It is the sheer ubiquity of it. This season there are 151 Twenty20 matches being played by the counties. There is no escape. With attendances dropping again this year, there are at least signs that the overkill will be addressed. If that is managed, then Twenty20 will have its place as a healthy addition to the game.

But it would be a mistake to see A Last English Summer as a whinge. Instead it captures all the flavours of a summer’s cricket: the grounds, the crowds, the players, the shots and the echoes of history. And it does so memorably, with an eye for the finest detail, including a well-struck ball tipping a row of empty seats like ‘invisible fingers depressing the keys of a piano’.

I would quibble with the choice to display the whole scorecard of a match when the accompanying chapter bears witness to one particular day of it. This dilutes the success of the book: to trap moments of a summer’s cricket in a corked bottle. The proof readers also require a slap on the wrist: a former England captain, current England batsman and present New Zealand captain all suffer misspellings.

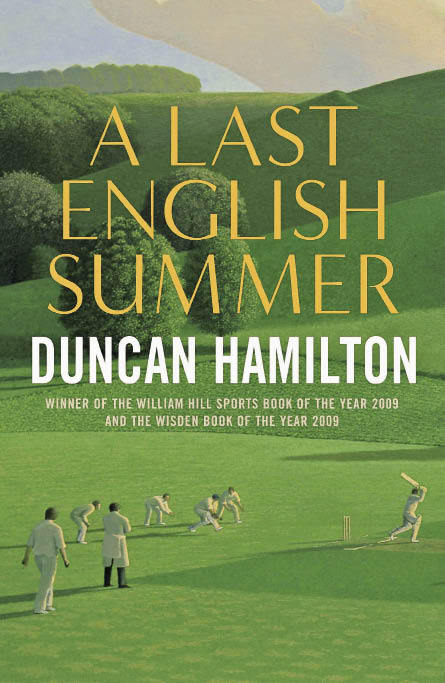

But how much does this matter when the book delivers so gracefully on the promise of the idyllic cricket scene shown on its cover? We endlessly worry about the state of the game, the loss of core values, the clutching of commercialism. Hamilton is acutely concerned. But ultimately he is left pleading: ‘Come quickly summer, come quickly.’ And so A Last English Summer is above all a beautiful, affectionate and timely reminder that cricket still is — and will be — about one thing most of all: pleasure.

Comments