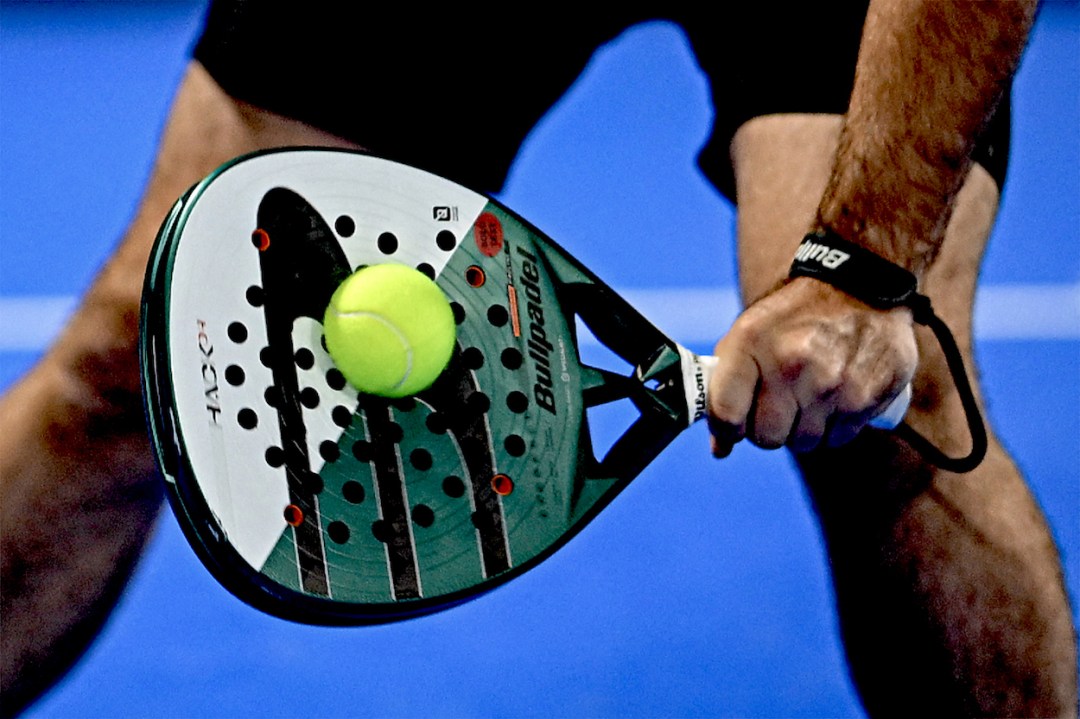

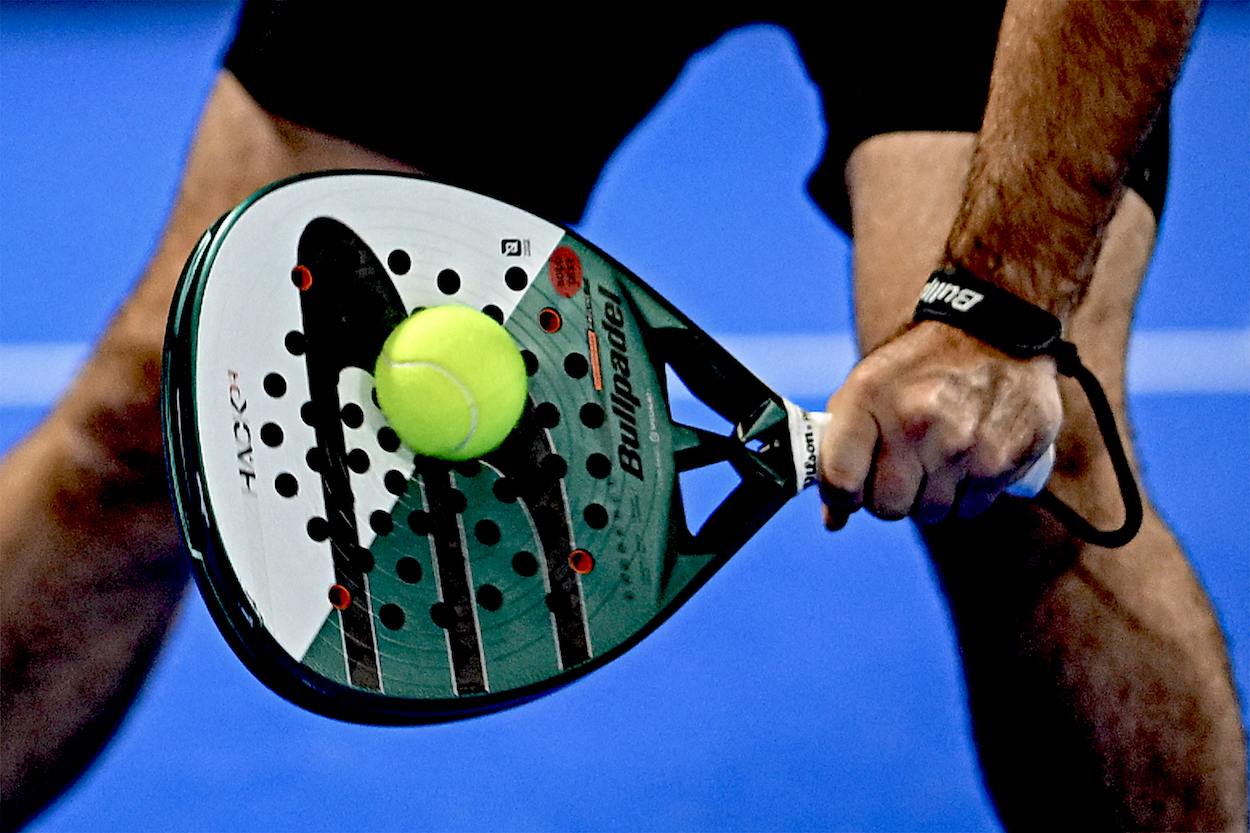

Why the hell not? I thought to myself as a friend invited me for a game of padel at her Oxfordshire members’ club, the grotesquely baroque Estelle Manor. As a self-confessed tennis head, I thought this might have the same feel of the restrained geometry and simmering tension of the tennis court that I have spent a lifetime admiring. I imagined a game close to squash but with the lightness of ping pong and the clipped etiquette of tennis. How wrong I was. Padel, I am sorry to say, is a disgrace. Not simply because it apes tennis in unfortunate ways, but because it is deeply uncivilised, like a dinner party with paper plates. Doubles players grunt and lurch around holding carbon fibre bats that look like squashed colanders, and the scoring has none of the absolutism of the tennis game because of the second chance granted you when the ball comes back off the walls. Love all? Hardly.

Plenty of people, however, are in love with padel. Founded by Mexican Santiago Gomez in 1969, padel is now the world’s fastest growing sport with celebrity devotees of all stripes and creeds. Prince William, Stormzy, David Beckham, Lionel Messi, Antonio Banderas, Serena Williams; all are devoted to the game that is easy to become addicted to but (notionally) hard to master. The fact that professional sportsmen and women also play it grants it a credibility that is, to my mind, misleading. In this country, padel is growing at an accelerated rate, with the kind of engagement numbers that the much-derided Lawn Tennis Association can only dream of: awareness of the sport has increased 70 per cent in the last 12 months and player numbers have almost doubled to a whopping, thwacking 235,000.

This at a time when other sports such as tennis, squash and real tennis are in decline. Racquet experts credit this rise, in part, to padel’s low barriers to entry; you don’t have to be especially athletic or coordinated to play, a bit like golf players can still be incredibly portly and continue to be huge enthusiasts for the game. UK padel, which manages courts across the country, estimates that the number of padel courts in the UK will grow exponentially in the next year, taking its current figure of 700 courts into the thousands; low barriers mean increased uptake and, presumably lower heartrates. Soon, sports clubs that struggle with attendance will soon have to install padel courts to keep their numbers up.

In some ways you could see this as all in the evolutionary order of things; more than that, you could say that it is healthy. Sport (especially those that involve balls, the most primal objects of all) has always spawned zeitgeisty offerings that eventually fizzle out. In the tournament model, the number of sports that actually catch on is relatively low. Take jai alai, speedball and tetherball, games that people have entirely ceased to have heard of – sporting flashes in the pan. It’s amazing, on this note, that the game of rugby, founded when William Webb Ellis picked up the football and ran with it in 1823, made it at all. Some things, it seems, involve a good deal of rule breaking to burst into the mainstream.

Padel has taken off for reasons that have nothing to do with sport

I thoroughly approve of rule-breaking, but it’s not the emergence of padel per se that interests me. Instead, I am fascinated the social ripples it causes. A quick straw poll of opinion shows that padel must be doing something right since it is both socially cohesive across class and divisive all at once; you can’t say that about croquet, a sport that people summarily dismiss as purely for chins with large gardens. ‘It’s genius,’ gushes one mother friend who describes it as ‘great fun without ruining my make-up’, while another replied instantly to check that I had not become ‘a private school padel bore’, and ending with the entreaty for the ‘all the padel w**kers to stop banging on about it’. In September, Tatler breathlessly declared that padel was the sport du jour, not for its skill but rather for its ‘electric fun and social relevance’. (No greater stamp of social approval could be granted than this, surely.) The article was accompanied by pictures of women wearing stilettos and draping themselves over various bits of padel equipment, captioned with the exhortation to ‘get your flirt on’.

As ever, Tatler has it. Padel has taken off for reasons that have nothing to do with sport and everything to do with accessible flirting and the whisper of sex, another sport with low barriers to entry. Therein lies the reason it provokes so much enthusiasm and so much rancour. And in this light, in the week of Jilly ’bonkbuster’ Cooper’s death, I rather salute it, as I believe she must have done. Just don’t invite me to play it.

Comments