The mother of a little girl in my son’s year at school recently committed suicide. On the surface she was a radiant person, smiling and full of light. Devoted to her daughter, successful at work, always good for a laugh at the school gates. No one — save those loved ones who knew her private struggle — saw it coming.

For days, waves of confusion and sadness emanated out through our patch of north-west London. This is the way of suicides in social groups. I’ve seen it before. They ripple and reach well beyond where they have any right to. But the peculiar thing about this tragedy was the way the news was disseminated — namely through the popular social media service WhatsApp.

Founded by two former Yahoo employees and purchased by Facebook in 2014 for a staggering $19 billion, WhatsApp is now the preferred form of communication for people in my demographic, by which I mean middle–class professional London mum-types. Clearly my tribe is not alone in this. With an estimated 1.5 billion users across 180 countries, WhatsApp, increasingly, is just how humans talk.

I joined my first group chat three years ago after being added by another mother at my older son’s nursery. Since then, I’ve joined and left dozens of other chats and spent countless waking hours being startled by ‘notifications’ that are of precisely zero interest or import. It’s incredibly annoying, but going off WhatsApp is not an option. Group chats are where I find out whether my son’s football practice is still on or where tomorrow’s lunch meeting is. It’s how I communicate with my husband, my tennis instructor, my colleagues and all of my friends and family in Canada and Europe.

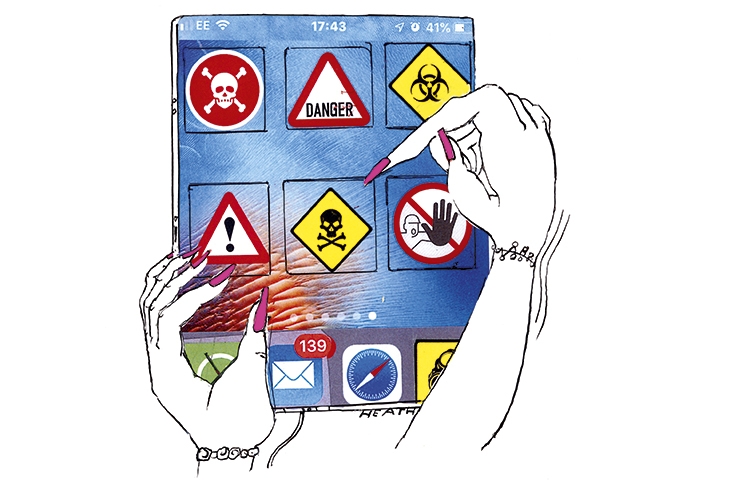

Like all sane people, I have learned that judicious use of the ‘mute’ feature and alert settings is key to maintaining Whats-App sanity. But muting doesn’t solve the problem of managing the sheer number of chats one must participate in just to live a normal socially and professionally connected life. I’ve deleted all algorithm–driven social media apps from my phone due to the intrusion and time-suck, but WhatsApp is different — seemingly more innocuous (no adverts, no algorithms) and yet also more maddening, for the way it’s woven itself into our daily lives, eradicating the possibility of escape.

Since acquiring WhatsApp five years ago, Facebook has put a lot of effort into assuring the general public it’s a safe and secure place to be. This year the company announced plans to merge all its messaging platforms into one big monolith based on the successful WhatsApp model. Mark Zuckerberg relishes pointing out that, unlike other messaging platforms, WhatsApp is fully encrypted, which feels about as reassuring as Harvey Weinstein pledging to protect your daughter’s virginity. The company has recently been in the news after it warned all users of a security breach involving spyware which a shady Israeli data-mining firm has deployed to hack the phone of an unidentified human rights lawyer. The announcement, while admirably transparent, also revealed the fallibility of WhatsApp’s encryption. We may feel the platform is safer and more private but that doesn’t make it a fact.

What unnerves me most about Whats-App though is not its potentially deleterious effects on privacy (though it’s an obvious concern) but rather its effect on our collective sanity. At last count I belong to nearly a dozen different WhatsApp chats, all related to my kids’ various schools, nursery, sports groups or social networks as well as a couple of project-related work groups.

In recent months some of these chats have been swept up in surreal flurries of hysteria fuelled by disinformation. The first were reports of a cereal bar called Astro-snacks, which had caused severe sickness and hallucinations in children. I saw this ‘warning’, complete with a photo of the brand packaging, on at least three different WhatsApp channels. The story swept London and several schools issued official warnings to parents before it was revealed as a hoax.

The second disruption was a petition calling for action on an apparent ‘radical increase in violent crime’ in my neighbourhood, citing several stories of children and parents being stabbed and beaten by gangs of men in balaclavas. Within a few days the petition went viral on WhatsApp, racking up hundreds of online signatures, and causing uproarious parental hand-wringing. One friend told me she burst into tears while reading it and begged her husband to consider moving to the country.

But a quick Google of the Met Police statistics in my area showed no discernible increase in violent crime, let alone a radical one. When I posted this fact-check on a couple of WhatsApp chats, the reaction was even weirder. Some people were reassured but others were deeply sceptical — rejecting the data outright. One school mum messaged me privately to express her support for the petition. ‘I don’t need statistics because I have eyes and ears,’ she wrote. ‘The threat to our children is obvious.’ In other words, who needs facts when you have feelings?

Middle-class parental anxiety is a well-worn cliché of modern life, like the apoplectic woman on The Simpsons who cries out, at every Springfield town meeting: ‘Won’t somebody please think of the children?!’ But what is new is the technology we use to share our feelings and the way it seems to exacerbate them. We know the pernicious downsides of Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, but what if WhatsApp is making us more anxious and unhappy than all three combined?

Which brings me back to the suicide. Within hours, the news was disseminated throughout the community on Whats-App. People began posting their responses, expressing grief, shock and an outpouring of worry for the bereaved daughter. But then, perhaps because the chat in question is normally used to discuss bake-sale logistics and games kit, the conversation took a strangely pragmatic turn. How was the school going to handle the news, some parents wanted to know. And what should we tell our own children? What exactly was the bereaved girl going to be told? And if she was told the truth (which it turned out she was), would she in turn tell her friends, thus corrupting our own small children’s innocence of suicide? Some parents said it was a personal choice and they didn’t want their child to know that it was possible for someone to kill themselves. Others worried aloud over their kids’ general morbidity and obsession with death. One parent floated the idea of calling the bereaved ex-husband so we could all get our story straight. Another got in touch with the headmistress and reported back the school’s plan.

All of this happened in less than 24 hours, and my notifications were through the roof. I was jumpy all day, tearful and distracted with my kids. There were Whats-App side chats being set up by parents who were upset at what was being said on the main chat and parents asking to be added on to chats they’d not previously chatted on before. Eventually I did the only thing a reasonable person can do in a WhatsApp anxiety funnel: I pressed mute.

It’s perfectly understandable for people to think of themselves and their families in the face of tragedy. Bad news has that effect — it makes us want to secure the perimeter and hold our loved ones close. But in this case, I think the medium distorted the message. A tragedy occurred and the anxieties of the community were amplified by the closed feedback loop of the platform on which we chose to discuss it. The news of a fellow mother’s death was horrible and crazy, but discussing it on social media just made every-one feel worse. The people who were voicing their sadness and anxiety doubled-down on their anguish, and the people who were silent froze, eyes widening in horror. Instead of tempering and comforting each other, as humans instinctively do when we grieve together in person, WhatsApp took all our collective bewilderment and whipped it up into something more familiar and less confusing, a feeling we could all grasp but from which good things rarely come. It took our sadness and turned it into fear.

Comments