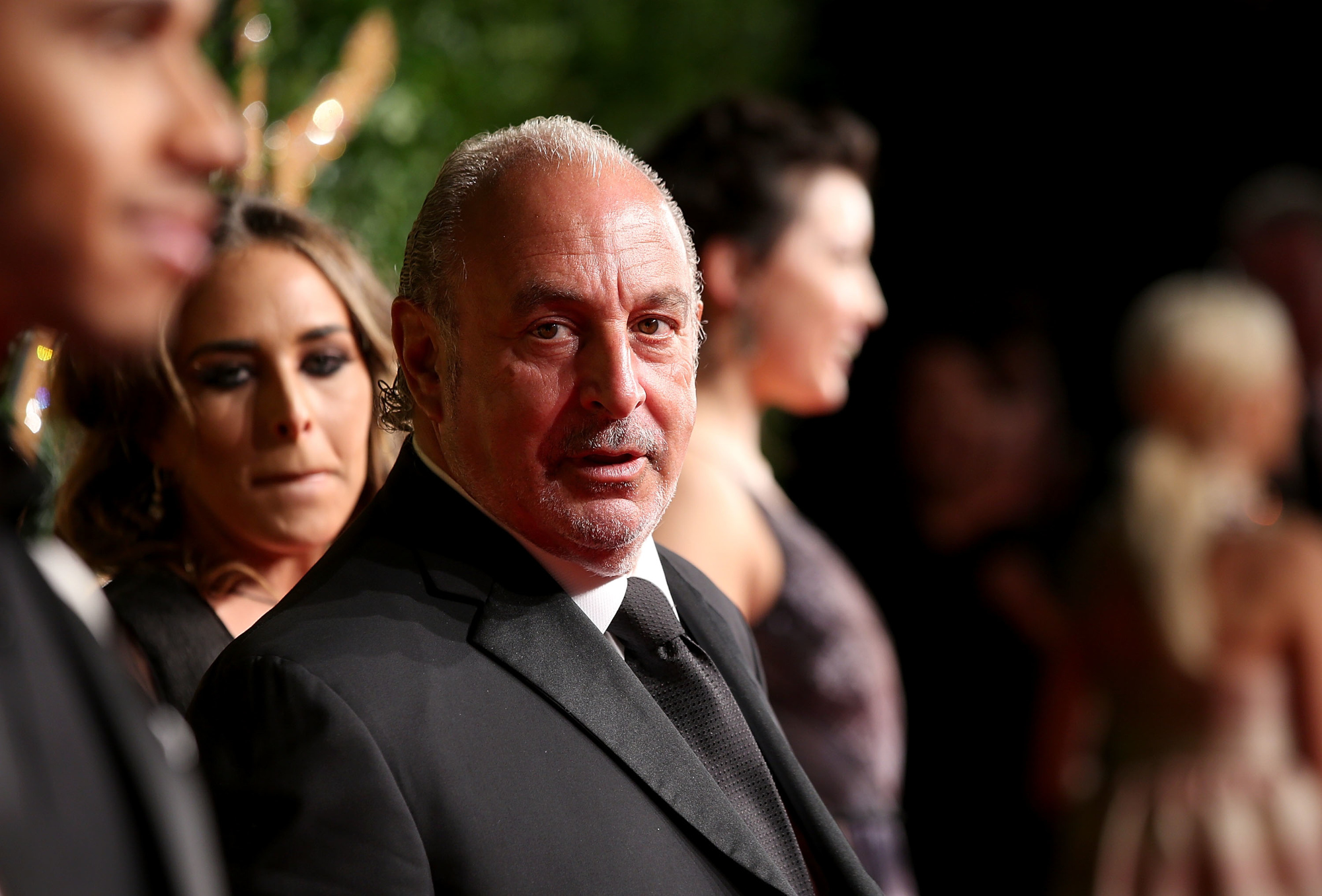

In a decision that will be welcomed by many in Parliament today, the European Court of Human Rights dismissed a claim by prominent businessman Sir Philip Green. Green had argued that his right to a private life and a fair trial had been infringed when a Labour Peer, Peter Hain, made a statement on the floor of the House of Lords claiming Green had been accused of sexual harassment and bullying by former employees.

The employees in question had signed non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) and so Green had obtained an interim injunction (pending a trial) and anonymity order from the Court of Appeal after he learned that the Daily Telegraph planned to report on these allegations. These orders effectively prevented the Daily Telegraph from reporting on the claims against him.

Both Houses of Parliament have adopted a sub judice rule, which requires Members to give the Speaker at least 24 hours’ notice before they discuss any matter before the courts. This is designed, in part, to avoid either House potentially influencing the outcome of a case.

When he stood up on the floor of the House in October 2018, without giving such notice, Hain stated that Green was a ‘powerful businessman using non-disclosure agreements and substantial payments to conceal the truth about serious and repeated sexual harassment, racist abuse and bullying’. He argued that this disclosure was ‘in the public interest’.

Article IX of the Bill of Rights (which protects freedom of speech in Parliament) stopped our courts from taking any action against Hain for breaching the injunction.

The House of Lords Commissioner for Standards dismissed a separate complaint against Hain under the House of Lords Code of Conduct. She concluded that allegations concerning the use of parliamentary privilege of this sort were outside her remit.

The result of Hain’s intervention was that the allegations were widely reported in the press and Green argued that his reputation had been seriously damaged.

Green complained to the European Court of Human Rights that Hain had used parliamentary privilege to circumvent the court injunction and to identify him. He contended that the state had a duty to take measures to prevent parliamentary privilege being used in this way and that the court should, amongst other things, find that there had been a violation of his right to privacy under the ECHR.

The Strasbourg court had previously considered the absolute immunity granted to parliamentarians under Article IX in a case called A v UK in 2003. In that case, a woman complained that her rights had been violated after an MP called her a ‘neighbour from hell’. She argued that she had no recourse against him in court and that her rights had been violated because she could not defend her reputation. The Strasbourg Court found in favour of Parliament in that case, but one of the judges who heard the case sent a shot across the bows when they stated the absolute immunity granted by Article IX of the Bill of Rights was disproportionate.p

Some 20 years after that case, the parliamentary authorities might well have worried that the European Court of Human Rights might take a more activist approach.

In the event, the Strasbourg Court concluded that, while there had been an interference with Green’s private life which had damaged his reputation, this did not amount to a breach of the ECHR. It determined that, in keeping with the well-established constitutional principle of the autonomy of Parliament, it was in the first instance for national parliaments to assess the need to restrict their Members’ conduct.

The Court conducted a survey of how parliamentary immunity works in the legal systems of 41 of the 46 member states of the Council of Europe and discovered most states protect Parliamentary statements. It said that it should be left to the state, and Parliament in particular, to decide on the controls necessary to prevent parliamentary members from revealing information subject to privacy injunctions.

However, there was a slight sting in the tail which may continue to trouble the parliamentary authorities. While it dismissed the claim by Green, the Strasbourg Court also indicated that there was a need for appropriate controls to be kept under ‘regular review’ at a domestic level. If such disclosures in Parliament, in breach of court orders, became commonplace, it would not be surprising to see further claims seeking to change the rules.

The outcome of this case is sensible, both politically and legally. At a time when many members of the opposition are lobbying to exit the ECHR, a finding against Parliament here would have been hugely problematic on a political level. While in theory the Lords could probably have made a simple tweak to their Code of Conduct to fix the issue, you can only image the response of some MPs, such as Robert Jenrick, to such a ruling. It would have been almost inevitable that we would have ended up in crisis.

More importantly, the privilege of freedom of speech in Parliament also places a duty on Members to use the freedom responsibly. In this case, Hain claimed the disclosures were in the public interest at a time when many such claims were being brought as part of the #MeToo campaign. While his statement was perhaps irresponsible, it was not suggested that the accusation was made maliciously. Moreover, unless it is fundamentally misused, it is arguable that that the absolute immunity in respect of freedom of speech in Parliament should be recognised as a significant benefit to our democracy – a fact recognised by many other parliaments.

In any event, irrespective of the merits of the judgment, the government will breath a sigh of relief that the Strasbourg Court has ruled against Green today.

Comments