For the past 18 months, it turns out, I have slept in a former royal place of worship. This has been less picturesque than it sounds. The old chapel on my corner of Rye Lane, Peckham, south London — named the Hanover Chapel because two of George III’s sons supported its minister, W.B. Collyer — was demolished to make room for tram tracks early in the last century. I live in the building that replaced it, a three-storey affair containing four flats, a pawnbroker and a branch of a sandwich chain. We are a mixed bunch up here above the pawnbroker. On the day I moved in, one of the other tenants ended a domestic dispute by opening a window and warning shoppers in the busy street below that she might have to jump. By the time I saw anything, she was walking safely downstairs to police and an ambulance, her partner having apparently already left in another official vehicle. I’m afraid I then took advantage a little: when reporting niggles with a new place to the managing agents, it helps immeasurably if you are able to add: ‘… and of course the police have broken down the front door.’

The disputatious couple, however, were not my most alarming new neighbours. That honour belonged to the animals. It was the cockroaches I saw first: one on a wall, then dozens, everywhere. Having taken a few deep breaths, I trolled the pound shops of Rye Lane for sealed plastic containers — into which I bundled all my food — and glue traps. All this made me feel very much better. I began to build a quite respectable collection of trapped cockroaches. But then, after a week or so, I ventured into the kitchen at night and found the traps being knocked over by a mouse. Mice are easy; cockroaches I could probably deal with; it’s a different matter to find them working as a team. I must admit, though, if only for legal reasons, that the landlord’s pest contractors had no difficulty evicting the lot.

Even with Collyer’s in the hands of the money-changers, there are at least four active churches on Rye Lane, with many others on its side streets. The more makeshift the circumstances of worship, the more splendid the name under which it is pursued. West African evangelism is the prevailing flavour, so it might be a West African thing. The street’s surviving purpose-built church — a handsome neoclassical edifice — is merely Rye Lane Baptist Chapel, but rooms above shops to the south of it are the Redeemed Christian Church of God House of Praise/Lighthouse Fellowship and the New Congregation of Cherubim Last Vessel of Salvation. A lock-up garage in a railway arch has become the Christ Healing Evangelical Church AKA The Royal Chapel. A hint of business jargon also helps impart gravitas, as with the Christ Apostolic Church International Miracle Centre (another room above a shop) or the Jesus Cares Crusaders Ministries International Solution Centre, a former nightclub.

Nor is it only the churches that speak of faith in Peckham. The most secular-seeming shops prove, on closer inspection, to display Bible verses on their awnings. Opposite the site of the Hanover Chapel is the carcass of Jones & Higgins, a department store which was once known as ‘the Selfridges of South London’, and which closed in 1980. Like the dry stump of some great tree, it teems with smaller forms of life: hairdressers, nail salons, money-transfer and international phone-card booths. There was a butcher here, Meat Divine, that had the fish symbol on its frontage. Sadly, it has left behind the things of the flesh and switched to financial services, trading under the name Divine Money.

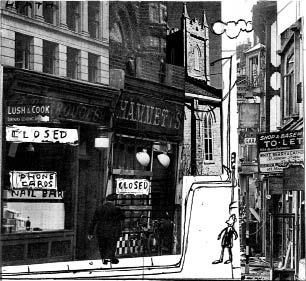

Rye Lane’s untidy vitality makes it a favourite target of regenerators. There is nowhere better, apparently, to situate your computer-generated image of a new urban square. One, in front of Will Alsop’s L-shaped copper-fronted library, has even managed to get itself built. It suffers from gusts of cyclists, seeking access to the old canal path behind it, and bears signs warning against public drunkenness, but there is a modernist shed housing a community art project on one corner and, every Sunday, a bedraggled but determined farmers’ market. None of it has had any discernible effect on the Lane. Local ‘vision statements’ therefore call for the creation of a second square, in front of the railway station, which would involve sweeping away a tatty 1930s parade of shops — including at least one small church, which operates out of a former R&B bar. Austerity has probably saved them for now. And the Lane seems to work too well to be susceptible to sudden gentrification: shops rarely stay vacant for long, even if the new tenants sometimes don’t feel the need to put their own names on the shop fronts. A well-stocked grocer announces itself as ‘Ray’s Furniture’ (another is called ‘Big Girl’, but that seems to be by choice); and a lingerie shop has traded happily, for several years, under the splendid old sign of ‘Regen’s for Baby Linen’.

For a vision of gentrification, you have to go a few yards west, to Bellenden Road, another old Peckham thoroughfare sent galloping upmarket by a combination of public money and artistic cachet. Regeneration grants at the turn of the decade adorned it with phallic bollards by Antony Gormley, whose studio used to be nearby. And while its initial crop of bohemian entrepreneurs — a junk-shop that on certain nights turned into a restaurant, a hard-to-describe business that seemed to involve carving faces out of pine — was thinned out when the economic climate hardened, their replacements are more businesslike, and the street seems to grow posher by the day. The old health-food shop has turned into a slick white-fronted deli. The fried-chicken place is reopening as a trendy bike shop, and the Rastafarian café is now something describing itself as a ‘literary kitchen’. It wouldn’t happen on Rye Lane.

Peter Robins is production editor of The Spectator.

Comments