In the early 1990s, the American novelist Mary Gaitskill suffered an abrupt awakening. ‘I lived in New York, I didn’t have a television, I didn’t listen to the radio. I didn’t even read magazines or newspapers very often. I was really too preoccupied with my own existence, which was hand to mouth a lot of the time,’ she says. ‘But when I was a little better off, I began to pay attention. I did get a TV. I did listen to the news a lot. And I was just like, holy shit. What a weird fucking world.’

What particularly astonished her, she says, is how central the fashion industry had become: ‘Models had always been glamorous figures, but it was suddenly they were the most important thing any woman could possibly aspire to be. They were just the most important female figure in the world. And it was kind of ridiculous.’

The culture was telling her that ‘we’ were like this; and then that ‘we’ were like that: that the world could be sorted into a shifting set of aspirational categories. In an essay prefacing her novel Veronica, set in the fashion world, Gaitskill calls it ‘the seed of deprivation hidden in a fever-dream of perfection’. It’s characteristic of her that Gaitskill responded to that with a fierce sense not only of how ridiculous those images were, but how seductive.

Gaitskill’s latest venture is the publication in book form of her essay Lost Cat. For those familiar with Gaitskill’s work, it may seem to cover unexpected terrain. The story collection that made her name, Bad Behaviour, drew in part on her own experiences as a teenage run-away and sometime stripper — and was set in a Manhattan demimonde of bad sex and marginal lives, drug addiction and emotional trauma. (‘The Secretary’, a superbly unsettling story about not-quite-consensual sadomasochism, was given what Gaitskill called the Pretty Woman treatment when it was filmed with James Spader and Maggie Gyllenhaal.)

She attracts the epithet ‘transgressive fiction’, though she says she doesn’t really understand why people call her work dark. ‘It could be because I’m so dark I don’t even see it,’ she says, deadpan. ‘I mean, I have written things that were rather dark — things that I would call that. But overall, no. I think people confuse sadness with darkness.’

Lost Cat, certainly, is a book about sadness — Gaitskill’s grief when a stray cat she adopted while staying at a writers’ retreat in Italy went missing shortly after her return to the States. But it’s a book that uses the story of the cat to explore other losses, other griefs: her relationship with her father; her relationship with her sisters; and, centrally, the writer’s love for a pair of deprived inner-city kids that she and her then husband, who have no children of their own, semi-fostered over several summers only to watch them drift away.

She’s fierce in the book about the idea that it’s sentimental or silly to be so unmanned (or unwomanned) by the loss of an animal. Of her father’s grief when his dog died within a year of both his parents dying, she writes: ‘His parents meant so much to him, he could not afford to feel their loss. The dog he could feel, and through the door of that feeling came everything else.’

Talking about it now, she says: ‘Family lore was that he didn’t cry when his parents died, his mother told him to be a brave boy. And so he was. Then his father died later. And he was still a brave boy. But the dog got hit by a car and he just went to pieces. And people thought that was strange. And it makes perfect sense to me.’

The cat itself, which she came to call Gattino, was a one-eyed scrap of a moggy: ‘He was a tabby, soft grey with strong black stripes. He had a long jaw and a big nose shaped like an eraser you’d stick on the end of a pencil. His big-nosed head was goblin-ish on his emaciated potbellied body, his long legs almost grotesque. His asshole seemed disproportionately big on his starved rear.’

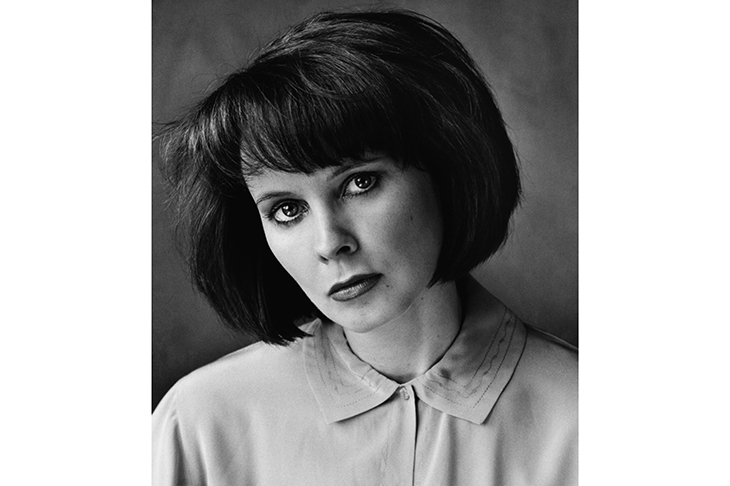

The book is very far from cutesy, then. And Gaitskill — though at 66 she could be taken for a spry Midwestern grandmother — is very far from cutesy herself. She’s precise and serious. She’s too well-mannered to say when you’ve asked a stupid question, but she doesn’t go out of her way to pretend you haven’t. And there’s that quality in her writing: it is marked by a sort of pitiless noticing, an absolute fidelity to the particularity of what’s there.

In our age of drastic oversimplification in public morality, Gaitskill’s work says: it’s more complicated than that

One of the strangest aspects of the book is that in the course of her bewilderingly obsessive search for Gattino, Gaitskill consults a number of psychics. This clear-eyed writer doesn’t seem an obvious mark for Madam Sosostris, but Gaitskill says it wasn’t the first time she’s consulted psychics. ‘Even in the moment I found it a little pathetic and weird that I would be doing that with an animal — but I actually believe some people are psychic. I probably shouldn’t say that in public. It’s probably the most embarrassing thing I’ve ever said in public. And I’ve said some embarrassing things.’

Gaitskill’s fiction is populated by characters who don’t always completely understand their own desires; who seek love, or fight against loneliness, in ways that turn out to harm themselves and others. Her work asks the reader to inhabit their worlds. In our age of drastic oversimplification in sexual politics and public morality, Gaitskill’s work says over and over again: it’s more complicated than that.

Her story ‘This Is Pleasure’, published in the summer of last year while #MeToo was still central in the public conversation, is a case in point. It centres on the intimate but not sexual friendship between Margot and her longtime friend Quin, as Quin finds himself cancelled over reports of ‘inappropriate behaviour’. Quin’s behaviour with women is unacceptable — but he’s not a predator or an abuser in a straightforward way. Anyone looking for a moral will come away baffled. The story is a perfect hall of mirrors.

It was inspired by a male friend of hers who was cancelled. His stock in trade, like Quin’s, was ‘paying women the kind of attention people crave’, ‘seducing people into revealing things about themselves’. ‘He would pull people into these things. And I think at first they did enjoy it. And then they felt humiliated and weird. And then he started to make fun of them for it afterwards…’

‘I loved him. I don’t mean romantically, but just as a person, but I could see how he was behaving. I can see why he got into trouble. But what I did not understand was when then there was a petition put out, threatening to boycott anybody that would hire him. And that just that just strikes me as really an overreach — like a grotesque overreach.’

‘I was drawn to [#MeToo] because it was a situation I was confused about. If I had a clearer feeling about #MeToo, pro or con, I probably would have written an essay […] But I wasn’t so sure. I mean, I could look at it sometimes and think, well, yeah, it’s a good thing that these assholes are getting their pants pulled down in public, but I don’t think it’s a good thing that they’re now barred from ever working again. I mean, if it’s suddenly illegal to be an asshole, we’re all in trouble.’

She writes in Lost Cat: ‘Human love is grossly flawed, and even when it isn’t, people routinely misunderstand it, reject it, use it or manipulate it. It is hard to protect a person you love from pain, because people often choose pain; I am a person who often chooses pain. An animal will never choose pain; an animal can receive love far more easily than even a very young human.’

Gaitskill took an epigraph from Auden for Bad Behaviour, and she’s as attentive as any writer I can think of to another observation of Auden’s: that the desires of the heart are as crooked as corkscrews. At one point Caesar, the adolescent boy she fostered, asked whether he and his sister could live with Gaitskill permanently.

‘It wasn’t possible,’ she says. ‘And I think it would have been really difficult for them. One of the reasons is that he was used to being physically disciplined.’ She told him: ‘I think you’d miss your Mom. I think you’d miss your neighbourhood. And we wouldn’t hit you when you acted out; I think you would miss that.’

‘And he said, “Why do you think that is?” I said, “I don’t know, really” — because I don’t. I think I remember saying: “If you can answer that question one day, you can make a million dollars.”’

Comments