I once asked Baroness Manningham-Buller, the former head of MI5, what she did to relax. Nailing me to the wall with her no-nonsense look, she said: ‘I keep sheep.’ A similar association with the animal kingdom resounds through Henry Hemming’s excellent new life of Maxwell Knight, the famous spymaster and possible archetype for Ian Fleming’s ‘M’.

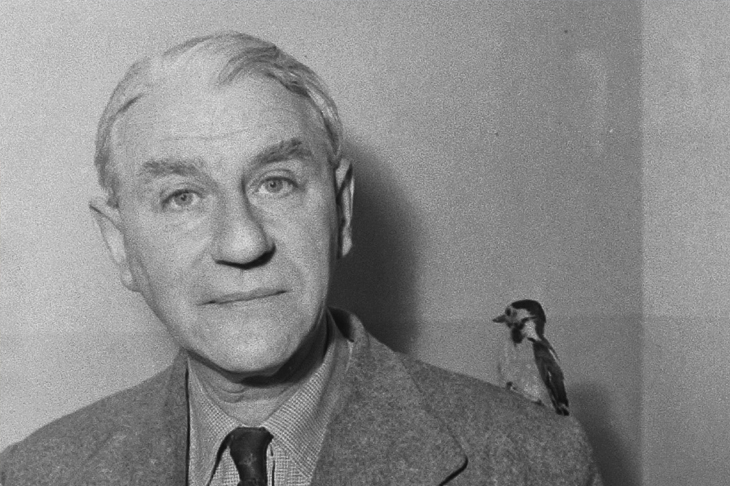

Knight’s family and friends observed that, at an early age, he had a particular way with animals that allowed him to bring them under his spell. As a young man he kept a menagerie in his small London flat consisting of a bulldog, a bear and a baboon. Following his retirement, he dedicated himself to sharing his animal experiences and wrote numerous books on exotic pets — not least his seminal How to Keep a Gorilla (1968) (the introduction cautions: ‘keeping a gorilla presents many difficulties’).

Knight’s intuitive understanding of animals, Hemming contests, also extended to other apes: ‘Just as he had “the gift” when handling pets, he inspired a preternatural loyalty from his agents.’ Hemming is not so lazy as to assume his subject to have been possessed of a quasi-spiritual power. As the author of In Search of the English Eccentric (as well as a bestselling life of the inventor and polymath Geoffrey Pyke), he has a honed ability to fathom the mysteries of his unusual subjects.

Drawing on Knight’s own writing, he describes a man who sought to make each of his agents feel unique — perhaps even loved. All spies are odd — pretending to be someone you are not for protracted periods is an odd thing to do —and spying is a lonely business. The attention and care Knight showed his charges, at a time when cold severity was the modus operandi of British professional life, bred great loyalty which could be deployed in his country’s service.

Knight’s tale started in the 1920s – a time when British fascists openly fought British communists and British communists won seats on councils and, on a few occasions, in Parliament. Having been a slightly lost jazz-loving youth, he slipped into the world of subterfuge as Richard Hannay might have done — through a conversation with a baronet in a gentlemen’s club. So began Knight’s own personal ripping yarn that lead him to high spymastery.

A virulent anti-communist, he first used the fascist movement to infiltrate and undermine British communism and then used the same skills, during the second world war and after, to undermine British fascism. In this he played a key role in strengthening the UK’s natural immunity to extremism. He was one of the earliest to be sensitive to Whitehall’s susceptibility to Soviet infiltration, and he correctly suspected that Anthony Blunt was in Russia’s pay.

Among his legacies within his peculiar trade was his decision to deploy a great many more women agents than had previously been acceptable. Knight was remarkably enlightened for his time, observing that ‘a woman’s intuition’ was ‘sometimes amazingly helpful and amazingly correct’. (If Casino Royale is anything to go by, Ian Fleming did not agree; Bond is very nearly done for by an inept female double agent’s emotional and professional bungling.)

Knight’s memory has not always been so hallowed. In the vacuum created by any official account of his professional life, wild stories have sprung up. The most notorious of these was a memoir by Joan Miller — one of Knight’s secretaries. She painted a picture of a man both homosexual and homophobic, neurotic, anti-Semitic and obsessed with the occult. Hemming dismisses her account as ‘fantastical’; and, even though he could have dedicated a little more space to debunking some of Miller’s specifics, he replaces it with the most convincing, balanced and intricate biography of this extraordinary figure that has yet been seen.

Hemming quotes, with sadness, Knight’s observation that the government officials of his day were ‘prone to regard “an agent” as an unscrupulous and dishonest person, actuated by unworthy motives’. This view of the profession as indecent and ungentlemanly is now, rightly, as obsolete as the redcoat. There are many reasons why such attitudes have shifted, but one is surely that operatives were made glamorous by Fleming and his Bond — and, of course, by Bond’s own spymaster ‘M’. In this accidental way, even in fiction, Maxwell Knight managed to modernise his profession.

Comments