It was in his play Back to Methuselah that George Bernard Shaw honoured a lesser known aspect of Charles Darwin’s originality as a thinker, when he described him as ‘an intelligent and industrious pigeon fancier’. Britain’s greatest natural scientist was indeed a keeper of fowl, with pigeons among his favourites.

The habit arose from Darwin’s instinctual recognition that in the animal-rearing experiments conducted over millennia by our ancestors, we had inadvertently stored away crucial evidence about the way in which all of life can change in response to environmental stimuli. It was part of his world-changing insights that he proposed how all the 200- plus pigeon breeds recognised in Victorian Britain, despite their astonishing breadth of variation, derived from a single parent species — the rock dove.

Katrina van Grouw wishes to remind us that Darwin was on to something which modern biologists prefer to overlook. Domestication is a vital window into the whole of the evolutionary process. Part of its importance is a matter of timescale. Natural selection operates on such a vast temporal canvas that it is almost impossible for one human, in the course of an individual life, to observe changes occurring in the physical forms of any animals. Not so, however, with pets and livestock.

A dog, canary, sheep or pig can be made to acquire extraordinary, exaggerated characteristics — massive increases in body-mass, complete changes of plumage colour, feathered feet, naked skin or ridiculously short legs — in the course of a few carefully manipulated generations. These vastly speeded-up mutations are what convinced Darwin of the insights offered by domestication. For van Grouw they are nothing less than a reaffirmation of the wider beauty inherent in all life’s processes.

She is thus on a one-woman mission to persuade us to take renewed interest, and acknowledge the wondrous processes at work, not in wild wolves and tigers but among pet dogs and cats. The book’s underlying moral is that evolution is as much at play in our living room as the forest.

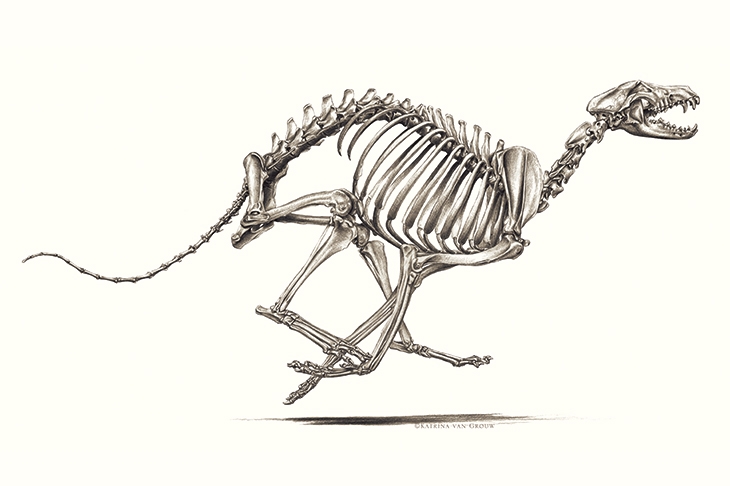

One of van Grouw’s methods of persuasion is to wow us with her exquisitely precise line drawings of skeletons and animal body parts illustrative of these anatomical modifications. One such tour de force is a double-page comparative sheet of 47 pigeon breeds depicting only their skulls. The variations demonstrated in their bill structure, skull size and shape far exceed those in the more famous Galapagos finches, which are always said to have played so decisive a role in Darwin’s thinking.

In its various parts Unnatural Selection feels like an homage to the standards of a bygone publishing age, through its large-format pages and its use of heavy sepia-coloured paper, but especially in van Grouw’s lovingly detailed monochrome drawings. Nor is it a coincidence that the images appear in a book published on the 150th anniversary of Darwin’s own masterwork about farmyard evolution, The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication (1868). One of the book’s goals is to remind us of the genius of van Grouw’s scientific hero.

Yet there is an irony at play here. As van Grouw acknowledges, Darwin’s own writings on domestication are muddled because he lacked true understanding of the machinery underlying the processes of evolution — namely chromosomes and genes. It was Darwin’s contemporary, the Czech pastor Gregor Mendel, who worked out the true basics of inheritance through his work on pea plants. Van Grouw goes on to give us this fully developed picture of evolutionary science in clear and simple prose. It is remarkable to observe how one of Britain’s most talented wildlife artists has undergone her own modification into an accomplished writer on science.

Yet there is a more troubling irony at work in her beautiful book. It concerns the author’s wish to revive an interest in domestication as a suitable theme for serious science. Not only do dog breeders or pigeon fanciers not talk to biologists, but there is often outright suspicion and even hostility between the camps. Typically, van Grouw’s efforts to enlist the co-operation of dog breeders in her enterprise were often met with rejection.

The problem is that many mutations wrought in pets, based on what seems a breeder’s bizarre aesthetic whim, have incurred charges of cruelty and have inflicted pain on their animal subjects. Van Grouw is alive to the issues, and gives us a classic example of the moral questions entailed in our unnatural selection of animals. Broiler chickens, cross-bred to activate a double-muscling gene, can grow to slaughter weight in just weeks. Economically valuable they may be, but these processes have created creatures that are barely able to stand and which suffer short lifetimes of pain in grotesquely cramped conditions. In short, domestication may be a richly adorned window on natural selection but its beauty is not always quite so obvious.

Comments