It’s October 1994 and I’m rooting around in a garage in a non-descript LA neighbourhood, a few blocks from 20th Century Fox. The garage is piled high with clothes, cameras, audio tapes, reels of film and, in pride of place, a Nazi storm trooper helmet.

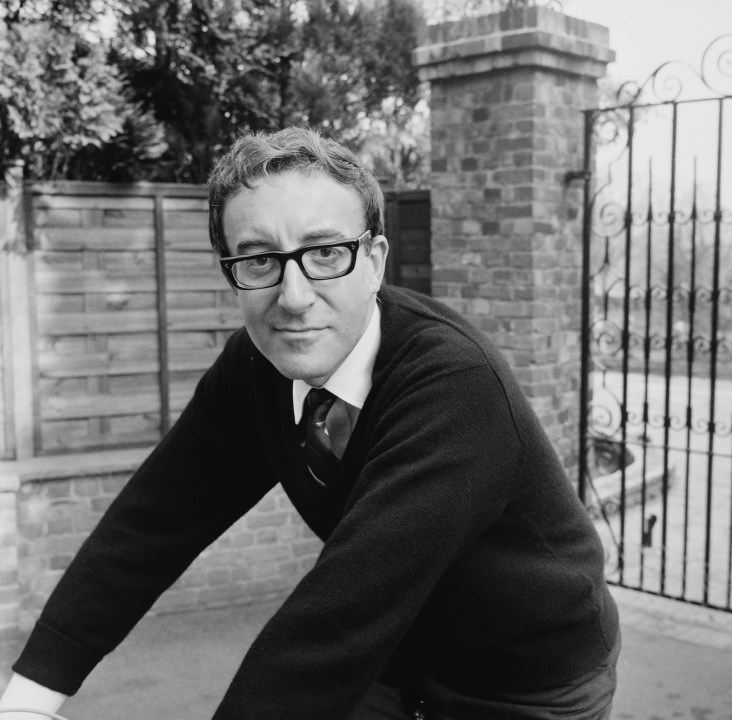

This was the last resting place for a mountain of paraphernalia belonging to comedy legend Peter Sellers, who was born 100 years ago today. The house was owned by Sellers’s widow, Lynne Frederick, who had been found dead there just six months earlier. Now her mother lived there alone and was the keeper of the trove. After several G&Ts together, she agreed to allow me access.

I was in LA filming a series of interviews for The Peter Sellers Story, a documentary for the BBC’s Arena. The garage was a side trip, but as I stood there surrounded by the remains of his messy life, I realised I’d stumbled across a fresh seam of Sellers gold.

One particular item caught my eye, an audio tape labelled ‘Interview with Mel Brooks’. Brooks was among the people I was due to interview in the coming days. He and Sellers had never worked together, but I knew they’d met and I wanted to talk to him about Sellers’s peculiar obsession with his first film, The Producers.

In 1967, the year The Producers was released, Sellers was in Hollywood making I Love You, Alice B. Toklas! He killed time in the evenings watching films in a private screening room with screenwriter Paul Mazursky. One night the projectionist offered up the as yet unreleased The Producers. The movie tells how third-rate Broadway producer Max Bialystock (Zero Mostel) teams up with an emotionally stunted accountant, Leo Bloom (Gene Wilder), to stage the musical Springtime for Hitler, written by a shell-shocked Nazi pigeon fancier. They intend it to be a surefire bomb. Only it isn’t.

Sellers fell head over heels in love with the film but was concerned that it would be overlooked, so he took out a laudatory full-page advert in Variety, calling it one of the greatest comedies ever made. Regardless, the critics hated it and audiences stayed away.

Undaunted, Sellers got himself his own print and made it his mission to show it to anyone who came into his orbit. As Sellers’s career imploded towards the end of the 1960s, his devotion to The Producers remained undimmed – a fact echoed by almost everyone I interviewed, including Michael and Sarah, his first two children. I took them back to the Surrey house where Sellers lived with Britt Ekland in his heyday. They sat in the still intact cinema built over the garage and remembered having to suffer through their dad’s favourite movie again and again. Sarah said Sellers took the print with him everywhere, even on holiday. In 1972 he went on Parkinson dressed as Franz the Nazi songwriter in greatcoat and storm trooper helmet (now consigned to that LA garage), reciting whole chunks of the character’s lines.

When I sat down with Brooks two days later, he claimed he’d never met Sellers. I took out a photo of them together on the set of a Sellers film shot in New York in 1963 and handed it to him

Watching The Producers again through Sellers’s eyes, the appeal became clearer. It contained all the elements of his background from childhood, through the war to The Goon Show. Beneath the late-1960s veneer of amorality, the film is essentially an old-fashioned Jewish showbiz story. Women are objects of derision or lust in this sealed male world: the only other significant female is the Swedish secretary (Lee Meredith) who Max and Leo both salivate over. Such a male cartoon of desirability would have appealed to Sellers, whose own relationships with women were disastrous, including his marriage to Britt, his very own Swedish object of desire.

Sellers had been born into a Jewish music hall troupe and had spent his childhood around the variety halls, where he would have witnessed an English version of this same New York Jewish showbiz world. The Goons, another sealed male world, revelled in the sounds and imagery of the second world war, trading on the wartime experiences of its stars Sellers, Spike Milligan and Harry Secombe. Like The Goon Show, The Producers was about men mucking around, hatching dastardly plans to make themselves rich and often ending with everyone being blown up.

When I sat down with Brooks two days later, he claimed he’d never met Sellers. I took out a photo of them together on the set of a Sellers film shot in New York in 1963 and handed it to him. He stared at it and went quiet. The cogs turned as he struggled to retrieve a lost memory.

Then something clicked as he recalled meeting Sellers and handing him a script. It was called Springtime for Hitler, the original title of The Producers. Brooks was a successful comedy writer then but not yet a director. He wanted Sellers to play Bloom and he remembers Sellers dragging him shopping while he tried to pitch the script. But Sellers was more interested getting Brooks’s opinion on clothes, jewellery and gadgets. Did Sellers ever read this small black comedy by this first-time director? Brooks thinks not, as Sellers was a huge star with a crazy schedule. That year alone he completed The Pink Panther, A Shot in The Dark, Dr Strangelove and The World of Henry Orient. One wonders when he finally saw the film in 1967 whether he remembered being offered it? If he did, it would explain a lot about his reaction.

On my last day in LA, I went back to the garage and was able finally to listen to the mystery tape. It seemed to have been recorded in England, on Sellers’s own equipment. It featured Sellers and Brooks fooling around, first as two Americans, then Sellers as himself interviews Brooks in Brooks’s popular guise as the 2,000-Year-Old Man – a character that could have come from The Goon Show.

There is an appropriate comic tragedy to Sellers being obsessed by a film that it turns out he could have starred in, made by a man whose work, as the audio tape shows, he was already a fan of but who had forgotten that they met. Sellers was always looking for ways of translating The Goon Show’s essence to the big screen. He’d ruined several films and driven certain directors to the edge of madness in pursuit of it. Now here was a film that seems to have captured it all, and to see it gloriously completed at a point when his own career and private life were in crisis must have been deeply frustrating. Yet rather than trying to ignore it and risk letting it gnaw at him, he became almost its sole industry champion.

Its failure at the box office may almost have suited him, allowing him to continue to evangelise about a forgotten film that the power-that-be had dismissed. He adopted it, then went further. By repeated viewing, by dressing up as one of its characters, by wholesale appropriation of parts of the script into his patter, he managed retrospectively to ‘star’ in The Producers through a kind of osmosis.

Comments