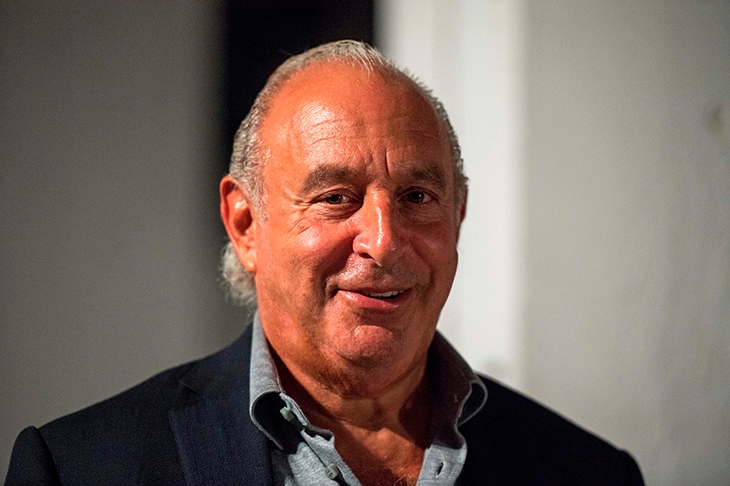

There really isn’t much left to be said about Sir Philip Green as his Arcadia fashion empire collapses into administration, taking the Debenhams chain down with it, unless a new rescuer steps in. An aggressive rag-trade wheeler-dealer since he started selling cheap jeans in the 1970s, Green was also once regarded as a brilliant merchandiser — until, it seems, he got too rich to bother keeping up with online competitors such as Asos, rising brands such as Zara and price-slashers such as Primark.

So he won’t be remembered for his fashion sense — as the era’s other trouble-prone ‘King of the High Street’, George Davies of Next and Per Una, might be. Nor will Green ever be given much credit for grudgingly agreeing to pay £363 million to bolster the bombed-out pension fund of BHS, two years after he tried to relieve himself of that potential burden by selling the store group for £1 to the former bankrupt (now convicted tax evader) Dominic Chappell.

What will be remembered are the £1.2 billion of dividends taken out of Green’s businesses in the name of his Monaco-resident wife Tina when the going was good, the swearing at journalists, the bullying allegations, the superyachts, the grotesque high-bidding at gala charity auctions, the gleaming bald pate — and the rising tide of job losses: 11,000 when BHS went down in 2016, now up to 13,000 at risk in Arcadia’s Topshop, Burton, Evans and Wallis outlets in the absence of new buyers for the brands.

When a parliamentary select committee savaged Green’s handling of BHS in 2016, I constructed a partial defence of him as ‘a rough-diamond dealmaker being brought down by a very rough form of justice’ — on the basis that not everything that has happened to high streets and pension funds in the past 20 years was entirely his fault, as some MPs seemed to think. But I’m not going to attempt that thought experiment again. One way or another, Green has left a nasty stain on capitalism. He should send back the knighthood, sail over the horizon, and hope to be forgotten.

Crypto-crazy

Bitcoin has gone berserk again. The notoriously volatile cryptocurrency more than tripled its price from a March low to reach $19,500 in late November, dropped back to $17,000, then soared again at the start of this week. Aficionados say it’s attracting new support from institutional investors, who see it as a substitute for gold and a hedge against a potential upsurge of inflation — and have perhaps forgotten that it lost four-fifths of its value after its last frenzied peak in December 2017, with no more real-world logic to the fall than there had been to the rise.

The bitcoin market is the wildest of unregulated online casinos, open to all manner of hackers and hucksters. The argument that it has unique integrity because bitcoin’s founding algorithm ensures only a finite amount can ever exist and can never be debased like state-run ‘fiat’ currencies is (as I may have said before) a fantasy best left to cultists and dope-smokers. Nevertheless, I notice a family-office fund manager telling the FT that ‘you need a bit of crypto in your portfolio’ these days — and if it’s going up like a rocket in these dismal times then maybe you do. But be sure to sell quick if you’ve clocked a lucky profit. And don’t swallow a word of the hype and hogwash.

Unreal City

The finale of our Economic Innovator Awards (see pages 30-31) brought me back to the City after a long lockdown absence. The event was joyous despite strict no-hugging. The studio high in the Leadenhall Street tower known as the Cheesegrater afforded glittering views. But something was amiss: only 100 of 7,500 desks in the building are currently occupied, I was told; and looking across into the brightly lit Gherkin (at 30 St Mary Axe) and Walkie Talkie (20 Fenchurch Street), I could see almost no one working at all.

As for the streets, they were -chillingly empty. I could not help but think of T.S. Eliot’s image of the ‘unreal’ City after the first world war, in ‘The Waste Land’ — ‘I had not thought death had undone so many’ — and wonder what on earth will become of this once-convivial hive of finance if office life never returns to pre-pandemic normality. Yet the infectious optimism of our award winners suggested an answer: it will take time, but I predict that our Innovator entry lists for next year and beyond will be crowded with creative entrepreneurs in every aspect of urban renewal.

Mystery in Tahiti

As a junior banker at Schroders in the 1970s City, I knew little of the power struggle taking place several floors above me. The firm’s eccentric proprietor Bruno Schroder favoured the high-energy, big-ego Australian Jim Wolfensohn for the chairmanship. Old-guard directors preferred the steadier hand of the elegant 13th Earl of Airlie, who won the eventual boardroom vote. Wolfensohn departed for New York, rescued the Chrysler car company and went on to galvanise the World Bank as its globetrotting, glad-handing two-term president.

Underlings recall a charismatic chief who emphasised his arguments by waving his cello bow, having been taught the instrument by Jacqueline du Pré. His death this week led me to Sebastian Mallaby’s biography The World’s Banker — which belatedly explains a mystery of my early career. One of the loans I looked after was to the Society of Jesus in Tahiti, though no one seemed to know why we were lending to a remote community of priests. Mallaby explains that Wolfensohn had one day received a call from the Provincial of English Jesuits to say that his Pacific brethren had come by some land and didn’t know what to do with it. Ever hungry for a deal, Wolfensohn immediately offered to finance a hotel on it — so long as they were happy to deal with him. ‘He was assured,’ Mallaby writes, ‘that being Jewish was no obstacle at all; half of Christendom had recommended him.’

Comments