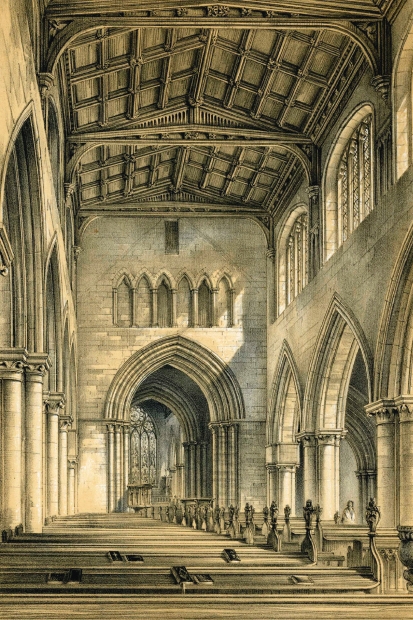

Briefing his illustrator for the jacket of A Handful of Dust (1934), Evelyn Waugh asked for a country house in ‘the worst possible 1860’. The result was a neoGothic extravaganza with a pinnacled entrance tower and spiky dormer windows — just the sort of thing that might have come from the drawing board of George Gilbert Scott, the most eminent architect of that time. Scott’s Kelham Hall in Nottinghamshire, its bright red brick distantly visible from the western side of the carriage as the train heads north from Newark, gives the picture perfectly. And if you strain to spot Kelham amidst its trees, no one could miss Scott’s Midland Hotel at St Pancras —same style, but twice as big — or that staggering object, the Albert Memorial.

Scott presented a large target to last century’s anti-Victorians. Earnest, fanatically diligent, pious, side-whiskered and bald, he was altogether a representative plaster grandpapa. Not only was his architecture hopelessly démodé; he was also accused of hasty over-production. Scott’s office was the largest in the country, and much of its output — there were 900 projects at least — must have been delegated by the man at the top. Worse, a great deal of this work concerned church restoration, which popular sentiment, following William Morris, often regards as a Bad Thing even today. Those seeking extra slingshots could quarry material from his posthumously published autobiography, with its unfortunate lapses into self-justification and special pleading.

We see Scott differently now. The suspicion that he worked as a front-man, securing commissions to be worked up by his minions, can be countered by plentiful evidence of his detailed involvement in all the most important projects. His hunger for fresh commissions was also matched by a canny sense of what his patrons might want. At Hamburg, for instance, the young Scott outflanked the home side to win the competition to rebuild the great church of St Nicholas. Its mighty stone spire in best German Gothic style stands to this day, the RAF having put paid to the rest. And as the hotel at St Pancras shows, Scott was also a true innovator, deploying new materials such as iron and plate glass in designs of medieval outline. In parallel, he published an influential defence of the Gothic Revival as the style best able to fuse ancient and modern motifs in a progressive spirit. Theory and practice advanced together.

Scott was also a fine scholar, especially in his restoration work. Modern scholarship shows that this was almost always rooted in a profound understanding of the fabric of each church and cathedral. Monuments such as the crossing of Ely Cathedral and Westminster Abbey’s chapter house look as they do today because Scott knew how to integrate this scholarship with his immense abilities as a designer. He also saved quite a few great churches from falling down altogether, a prospect which seems curiously not to have troubled Morris very much. In turn, modern restoration techniques have rejuvenated some of Scott’s own landmarks, the Foreign Office (a swerve into classicism), the Albert Memorial and St Pancras among them.

Gavin Stamp is uniquely equipped to write about Scott. He has edited a full reissue of the autobiography, and published a judicious study of the great man’s brilliant but wayward son, the architect George Gilbert junior (alias ‘Middle Scott’ — father in turn to the youngest of the Gilbertian trio, Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, designer of Liverpool cathedral, the red phone boxes and Battersea power station). This richly illustrated new book includes a substantial biographical essay, and shows plenty of unfamiliar commissions to balance the major works. Here is the best introduction to one of the central figures of the Victorian age.

Comments