Let’s think about it. How did Harold Pinter write his masterpieces? And why are they praised so much more lavishly than the scribbles of his contemporaries?

Let’s think about it. How did Harold Pinter write his masterpieces? And why are they praised so much more lavishly than the scribbles of his contemporaries? Moonlight, his 1993 play, has been slickly revived at the Donmar and it opens with a dying pensioner sprawling luxuriously in a double-bed and ranting at his wife. Across stage his sons engage in madcap vaudevillian banter. Other characters wander in and speak fluent nonsense. A girl, who is also a ghost, articulates charming drivel about moonshine and memory. The characters fail to communicate and the dramatist fails to communicate why they fail to communicate. Typical Pinter.

He adopted this uneasy, audience-intolerant method because he reached his creative maturity in the mid-20th century when literature had generated a shadow industry, academia, which was more powerful and prosperous than the art it elucidated. Shrewd writers like Pinter and Beckett copied the techniques of conceptual painters: withdraw detail, blur clarity, obfuscate meaning.

Literary critics and biographers responded by giving these mystifiers pride of place over the clarifiers. Why? Simplicity and definition are less amenable to academic study than allusiveness and obscurity. A boffin who lectures about a lucid, unequivocal play soon runs out of words. But one who expounds the meaning of a smudged hieroglyph can keep rabbiting on till pension day. So the exaltation of withholders like Pinter and Beckett over entertainers like Rattigan and Simon Gray has nothing to do with artistic merit. It’s about economics. Members of the lumpen commentariat can harvest a richer crop of tracts and monographs from an abstruse dramatist than from a plain-speaking one.

Pinter always dropped expositional detail from his plays — check the early drafts and you see key information being deleted with thick pen strokes — and these omissions guarantee that the profs on campus can keep their Biros busy searching for an answer that’s been cut out. This self-vandalising impulse destroys Moonlight as a serious work of art. The ruins are a slender, very silly and occasionally hilarious play. ‘Why am I dying?’ demands the corpse-to-be. ‘I haven’t done anything wrong.’

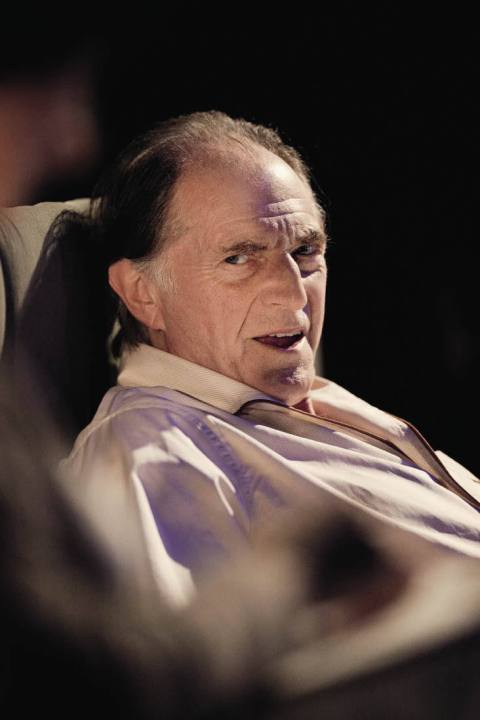

David Bradley has fun as the Albert Steptoe of the piece delivering thrusts of derisive merriment. ‘Is that a winding sheet?’ he asks his studiously embroidering wife. I’m afraid the rest of the cast are a gang of stiffs with nothing to do but jabber. Far from being a masterpiece, as some critics still swear, this is the geometric opposite. A play about love, grief and loss which fails to engage the emotions or to illuminate anything about its chosen themes. This is the last glimmer of Moonlight London will see for a while.

Mike Leigh’s play Ecstasy, set in a squalid bedsit, shows us two varieties of urban living. Chirpy Dawn has three gorgeous daughters and a stormy but solid marriage to an Irish builder, Mick. Her schoolfriend, Jean, is a study in woe. An alcoholic halfwit with a deadbeat garage job, Jean is so lacking in self-confidence that she lets men rape her. ‘Oi just drink all the toi-eem,’ she complains in her Brummie accent.

Mick’s old friend Len, recently divorced, shows up unexpectedly and the four chums enjoy a night of drunken chat which is meandering, depressing and amusing in roughly equal measure. Dawn shows off a shoplifted skirt. ‘No one buys anything from C&A. You just go in and help yourself.’ Her husband Mick, from Cork, is asked what he’d do if he had a million pounds. ‘Buy a pub. With a sign over it. No women. Self-service.’ Mick, from Cork, a builder, buys a pub: it feels a touch formulaic. The slow-burn issue is whether gin-swilling Jean will pair off with dull but dependable Len, and the outcome is contrived and sentimental almost to the point of propaganda.

The play belongs to Leigh’s social theory phase. He wanted to be a Dickens for the industrial poor, exposing the horrors of their aimless, desensitised lives. But in 1979, when the play is set, the British underclasses were among the most affluent people on earth. Back then the free world was confined to north America, western Europe, Japan, Australasia and white South Africa. Every other being on the planet endured third-world destitution or Marxist tyranny (or both). Leigh’s insistence that we shed tears for these snug well-kept folk feels more than a tad manipulative.

There’s terrific work from the cast, though. Sinead Matthews — Babs Windsor with range — is a comic treat as Dawn. And Siân Brooke, though miles too pretty to play Jean, brings pathos and humanity to the gangbanged wretch. I hope this play triumphs but I fear that its cheerless themes and its gnarled regional accents may deter the mighty dollar which, as the evenings lengthen, becomes the dominant force at the box office.

Comments