In 1694 London’s streets echoed with a call to the piratical life:

Come all you brave boys, whose courage is bold, Will you venture with me, I’ll glut you with gold?Make haste unto Corona, a ship you will findThat’s called the Fancy, will pleasure your mind.

In a week-long orgy of savagery, women flung themselves overboard to escape gang rape

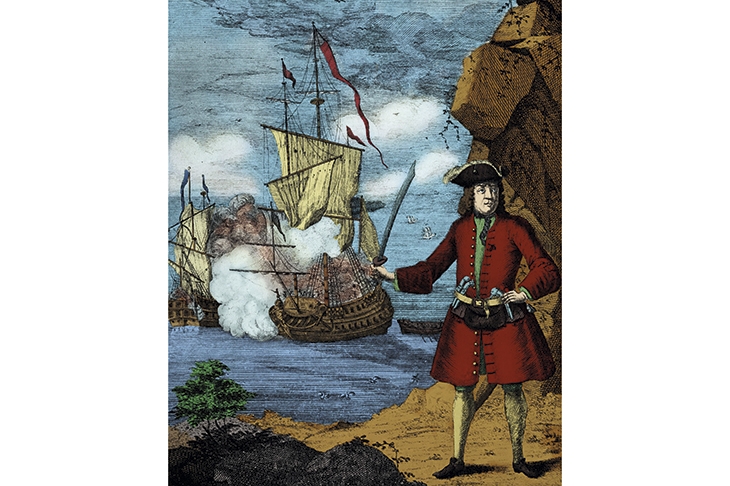

The ballad was supposedly written by the ‘pirate king’ Henry Every, who was about to pull off an astonishingly daring raid. In one fell swoop he’d landed the equivalent of $20 million by today’s reckoning, and — some said — married an Indian princess to boot. He’d also vanished off the face of the earth. His crime not only sent shock waves round the globe; it insulted the world’s richest man and gravely jeopardised the fledgling East India Company.

In the summer of 1695 the Ganj-i-Sawai (or Gunsway, as it was anglicised), a vast, armed dhow belonging the Grand Mughal Aurangzeb of India, was returning from the Hajj filled with treasure and pilgrims when it was intercepted between the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. The Fancy, a smaller, much faster ship, commanded by Every, pulled alongside and opened fire, throwing the Gunsway into turmoil. A cannon unexpectedly exploded on her deck, adding to the chaos, and her main mast was felled by a direct hit, allowing her to be boarded by Every’s crew. A week-long orgy of savagery and torture followed, during which many of the female passengers flung themselves overboard, preferring death to gang rape.

After his great ship was eventually sent on its way, Aurangzeb blamed the outrage on the East India Company — some of

Every’s crew having declared vengeance for the siege of the Company’s fort in Bombay — and stipulated there should be no further trade with the English until Every was caught. The government acquiesced, sparking the ‘global manhunt’ of the book’s subtitle — but without success.

In a further effort to appease Aurangzeb, a show trial was organised in London. The defendants — the few crew members who had foolishly returned home — were allowed no defence counsel, so had to face alone England’s greatest lawyers, who presided both as judges and counsel for the prosecution. Even so, it took two trials to convict them, the first jury having found them not guilty. By then they had acquired a Robin Hood status of gallant rebels — with ballads celebrating the atrocity as a plucky act of defiance.

Johnson has to perform a delicate balancing act between condemning the brutalityof Every’s men and lauding their triumph. He tries to present the pirates’ code as a sort of prototype of democracy — the sailors’ decisions being put to the vote, and unsatisfactory captains made answerable. But the Gunsway rapes left a dreadful legacy. Within a couple of decades Edward Teach — the notorious Blackbeard — would force his 16-year-old wife to prostitute herself with six of his crew.

And what of Henry Every himself — if that was even his name? (He was variously known as John or Jack Avery or Evory or Benjamin Bridgeman, among other aliases.) He remains a phantom. His birth, possibly in Devon, remains obscure, and we don’t know when or how he died. He was last seen setting out alone, after landing with his remaining shipmates on the north-east coast of Ireland. But he must have been a charismatic figure, chosen by a group of pirates as their leader over another captain with long experience of raiding in the Indian Ocean. Since he never boarded the Gunsway himself, he is presented as an almost gentlemanly figure — above the fray, but powerless to stop the violence he had unleashed.

Johnson cautions against romanticising the ‘populist strain that runs through Every’s life as a pirate’. But he still refers to the incident as the ‘crime of the century’, committed by the world’s ‘most wanted’ — and dismisses the story of the princess as ‘a tall tale’ while conjecturing at length about it. Crime as romance appears irresistible.

Comments