Keith Richards is a cross between Johnny B. Goode and Captain Hook. Like Johnny, he can play the guitar just like ringing a bell. Like Hook, he is selfconsciously piratical in costume, speech and behaviour— though he is modest about his contribution to Johnny Depp’s performance in the Pirates of the Caribbean. ‘All I taught him was how to walk around a corner when you’re drunk — never moving your back away from the wall.’

Johnny B. Goode never ever learned to read or write so well, but ‘Keef’ ain’t half bad. He wrote ‘Gimme Shelter’, after all, one stormy afternoon in Mayfair while his girlfriend Anita Pallenberg was in Notting Hill, making Performance with Mick. And on this gig he is ‘with’ his old friend James Fox, who is a groovy writer (White Mischief), and has done him proud. Life is funny, filthy, wise and scholarly, and disconcertingly decent, but the most surprising thing is how much he can remember.

An only child, he grew up on a council estate in Dartford, Kent, with his musical mother Doris and his disapproving father Bert, who in old age looked like ‘a retired pirate’. His primary schoolmate Mick came from a detached house on what, had there been a black side of town, would have been the white one, and at 11 plus Mick went to Dartford Grammar in a red blazer, and Keef to Dartford Tech, which set the tone of their relationship.

Keef was a choirboy, which explains a lot, and also, incredibly, the leader of Beaver Patrol, Seventh Dartford Scouts. He still admires Baden-Powell, and his approach to piracy is obscurely informed by the Boy Scout spirit: he is a stickler for ‘the code’.

He bumped into Mick again at Dartford station in 1961, and they became soul twins, bound by a passion for the Chicago blues. Soon afterwards they met Brian, who was a whiner, a primper and ‘a cold-blooded, vicious motherfucker’. The Stones were created by Ian Stewart, who was excluded from the official line-up because he played piano and looked wrong. Bill was recruited for his amplifier, and Charlie only when they could afford him, which they did by eating less and shoplifting more.

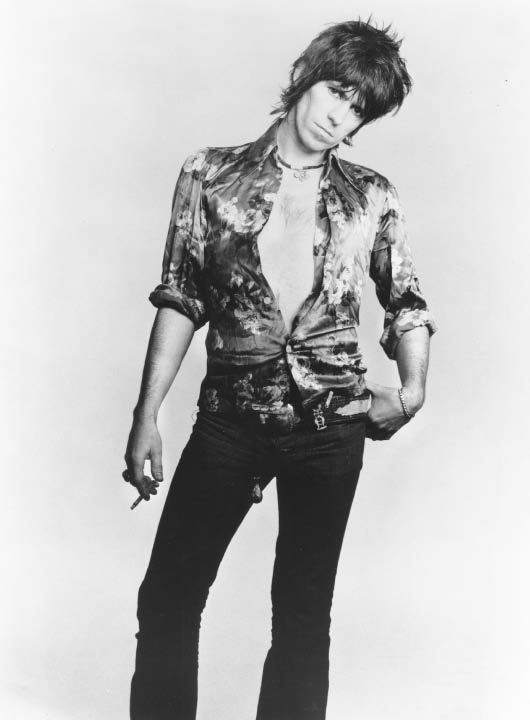

Soon they were world famous, and Keef was hanging out with Cecil Beaton, who admired his ‘marvellous torso’, and Arndt Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach (‘a degenerate even by my standards’), and Captain Hook’s fellow Old Etonians Robert Fraser, Christopher Gibbs and Mark Palmer. ‘I’ve never known if they were slumming or we were snobbing’.

He has fond memories of many ‘chicks’, ‘bitches’ and ‘mamas’, above all of Anita, whom he took from Brian — ‘It’s said that I stole her. But my take on it is that I rescued her’ — and Mick for a while took from him. Unlike Mick or Bill, he is uninterested in sex for its own sake, and is in touch with his inner Sir Galahad.

He writes at great length about drugs, for which he is a terrific advertisement, rhapsodising about fluffy pharmaceutical blow and slabs of hash the size of skateboards, and fondly recalling his gunplay in iffy deals. His secret is not to overdo it, to take the Sherlock Holmes approach: ‘A little bit of this, a little bit of that, couple of downers, a couple of uppers, coke and smack . . .’ John Lennon, who was ‘a silly sod in many ways’, never got the hang of it, and would turn green and throw up.

And he is thrilling on the subject of rock’n’roll — although ‘It’s nothing to do with rock. It’s to do with roll.’ He got the sound of ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’ and ‘Street Fighting Man’, for example, by playing an acoustic guitar into a cassette player, overloading it to the point of distortion, while Charlie played on a 1930s practice drummer’s kit — ‘that’s really what it was made on, made on rubbish, made in hotel rooms with our little toys’.

The other big topic, obviously, is his epic quarrel with Mick. He rather teases the reader with this, sustaining the tension with compliments about Mick’s versatility, charm and skills as a songwriter, but about nine tenths of the way through he really lets him have it. According to Keef, ‘that bitch Brenda’ is addicted to flattery and power, cannot hold his drink and has a ‘tiny todger’. But his main offence is to have broken faith with the ‘pirate nation’ of the Stones. Having always seen everyone else as ‘basically hirelings’, he started to treat the band that way, which was intolerable. However soured it may be, though, it remains a love affair: ‘Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin always remind me a bit of Mick and me.’

Life is the best book of its kind since Bob Dylan’s Chronicles.

Comments