It’s not surprising, perhaps, that Emil Cioran isn’t much read in England. Born in Romania, but winning a scholarship to the University of Berlin in 1933, Cioran was an avid supporter of both the Nazis and the Romanian far right group, the Iron Guard. His writing is bleakly nihilistic, his titles a hint to what lies within: On the Summits of Despair, A Short History of Decay, The Trouble With Being Born. Cioran was perhaps the greatest 20th-century practitioner of the aphorism, that ancient, fusty, patrician form associated with Hippocrates, Erasmus, de la Rochefoucauld and Pascal.

Viewed in a certain light, though, a kind of mordant humour begins to emerge from Cioran’s writing. It’s hard to read pensées such as ‘We have lost, being born, as much as we shall lose, dying. Everything’ without the creeping realisation that the author is having a bit of fun with the public perception of his work. It’s this humour — dark, self-mocking, corporeal — that self-confessed Cioran fan Don Paterson channels in his hugely enjoyable collection of aphorisms, The Fall at Home.

It takes a degree of chutzpah to pen a single aphorism, let alone a collection. It’s a form that presupposes the author’s wisdom and his (there are tellingly few female aphorists, pace Dorothy Parker) right to bestow it. In the wrong hands an aphorism can either feel hectoring and judgmental or bloodless and obvious. Paterson’s book, which brings together selections from his three previous collections of aphorisms and a good deal of new material, offers the reader a bracing combination of the profound, the comic and the often hilariously self-revealing.

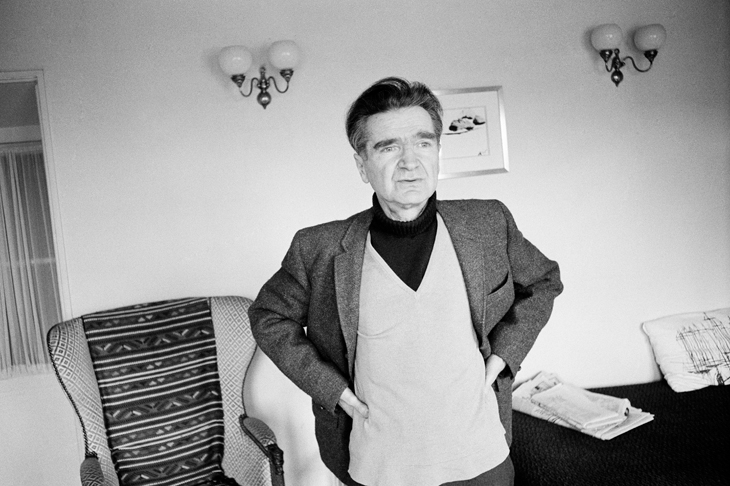

Paterson arrived on the poetry scene with the equally gifted Simon Armitage in the early 1990s, a kind of versifying Baddiel and Skinner. Paterson’s first collection, Nil Nil (1993), feels like a relic of that vain-glorious decade, all (elegantly phrased) booze and birds and braggadocio. Since then, as he’s moved through middle age and parenthood, his poetry has become more reflective, with both his 2009 collection Rain and 2015’s 40 Sonnets establishing his place as one of the most moving and lyrical poets working in English today.

Paterson’s aphorisms, as one might expect, turn on many of the same themes as his poetry. There’s plenty of sex, death, love, and music — Paterson was a professional jazz guitarist. He nods to other aphorists — Wilde is clearly there behind the lapidary ‘All I learnt was discretion’ and ‘The immaculate are tainted waiting to happen’, while Cioran appears in the italicised exhaustion of: ‘Too late for everything; not too late for anything; I flip between death and eternity, and either way nothing gets done.’

There are also regular and very funny glimpses into the bitchy, back-stabbing world of the contemporary poetry scene. Paterson — or at least the ribald, rebarbative persona he puts across in his aphorisms — enjoys cultivating his enemies, seeming positively to relish a slight or a bad review: ‘I decided to bury the hatchet, and the back of his head seemed as good a place as any.’ He runs into a ‘coeval’ (there appear to be few friends) for the first time in ten years. ‘He has become monstrously fat. I tell him, truthfully, that it is a perfect delight to see him.’

The aphorism is, as Paterson puts it, ‘the rational articulation of a fleeting hysteria’, and therefore the ideal mode for our techno-panicked age. Indeed, far from being nostalgic or marginal, as Paterson seems to consider it, the aphorism is perfectly fashioned for the etiolated attention spans of the permanently wired, made for Tweeting, or for plastering across some inspiring vista on Instagram. At the end of the book, Paterson provides pointed potted biographies of the principal aphorists, reserving most space for Cioran. If Cioran — nihilistic, rancorous, austere — was the great aphorist of the 20th century, Paterson may be his sunnier 21st-century reincarnation.

Comments