Once you grasp the essential triviality of the Olympics, the Cultural Olympiad falls perfectly into place, says Lloyd Evans. Even Shakespeare can’t escape

Once you grasp the essential triviality of the Olympics, the Cultural Olympiad falls perfectly into place, says Lloyd Evans. Even Shakespeare can’t escape

Funny business the Olympics. No one seems to want it. Clearly it doesn’t belong here or anywhere else. So what’s it for? The main athletic competitions — ‘track and field’ — are disciplines devised by Greek hill-farmers during the Iron Age to improve their skills in battle. The field events, like discus and javelin, teach you to throw heavy and/or pointy things at your enemy. The track events, like sprinting and hurdling, teach you to run away from your enemy if he happens to be better trained than you in the field events. We don’t need these Homeric survival techniques any more. And their do-or-die ethos is no longer part of our sporting culture.

Our settled, peaceful way of life inclines us to softer, more collegiate games such as football, tennis, darts, snooker and golf. These are our mass-sports and, if they feature in the Olympics at all, it’s out of courtesy rather than necessity. So although physical competition is a minor concern, the Games still tests human prowess in three main areas: advertising, pharmacology and municipal logistics.

Advertisers fight to squeeze the most coverage from the smallest possible investment. Athletes flock to the Games to find out which apothecary has concocted the best masking agent this time. And host cities vie to see who can build the biggest and most elaborate unwanted sports park.

Of these three contests, the construction programme is the most significant. At first sight it seems absurd to sink cash into a vast, redundant civic project. But these pointless building splurges are a constant throughout history. What purpose is served by the Pyramids? Who needs Versailles or Blenheim or Anthony Caro’s ‘Sculpture Two’? Building-for-no-reason seems to answer some deep human need. The residents of Great Torrington in Devon, in common with rural towns elsewhere, come together each year to put up a whacking great Tudor mansion or a Saxon barn that they then burn to the ground. What for? It’s fun. It’s mad. And it’s exhilarating for a community to demonstrate how much spare capacity it has. And that’s what the Olympics is about: the futile investment of time and manpower in lavish and impractical ornaments. In that respect it resembles art in its purest and earliest forms. And once you recognise that the Games involve the orchestrated squandering of resources you’ll begin to appreciate its essence. I live about ten minutes from the Olympic site and I saunter over there regularly to draw in great draughts of its luxurious and monumental triviality.

The spirit of waste and megalomania is catching. The phrase ‘Cultural Olympiad’ may have gone Beep! on your artistic radar. And you may even have wondered when it’s going to start. It’s nearly over. For the past four years the Olympiad has been steadily raising a small mountain of literary, horticultural and conceptual achievements. All are gloriously silly.

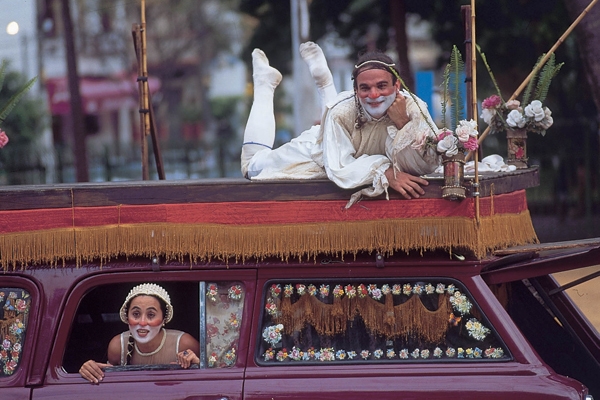

The tsars of the Olympiad commissioned 12 artists to devise works that ‘use the UK as a blank canvas’. Each piece consists of a glib visual gesture dumped on a plinth of deluded rhetoric. In the Home Counties, for example, citizens have been asked to donate flotsam to a gang of Noahs who will build an ark to ‘sail the south-east coast and become a focus for celebration’. Lancastrians can enjoy ‘Column’ by Anthony McCall, ‘a slender, sinuous, spinning column of cloud rising into the sky from the surface of the water in Merseyside’. Nottingham will benefit from a collection of ‘30-foot hand-crocheted lions’ which the city has, of course, been crying out for for years. Those in the east of England are being enlisted to write ‘stories’ for a People’s Encyclopedia to be shared online with the rest of the world. The gardeners of Swansea are growing veg on a disused sports ground for a ‘communal cook-off’. And in Llandudno, a beaten-up DC9 will be dragged along the promenade by North Wales Rugby Team while 600 schoolkids pose as airstrip landing lights and a vapour trail.

Clearly, the quest to create the most laborious piece of futility is proving highly popular. The UN has joined in, too, by calling on countries at war to lay down their arms during the Games. Presumably Britain, as host nation, is free to carry on shooting the Taleban.

Shakespeare, too, whether he likes it or not, has been press-ganged into the Olympiad. Opening on 23 April, the World Shakespeare Festival bills itself as the largest celebration of Shakespeare ever staged. A plague of events, stunts and playpen workshops will sweep across the country. Here’s a typical sample. In the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford a company called Squidsoup will invite toddlers to approach the Bard’s language by decorating the walls with bits of text in the shape of creepy-crawlies. ‘Stand and watch,’ says the blurb, ‘and the creatures may venture forward, wanting to befriend with messages and questions.’

The most ambitious — and possibly the most futile — project of all is Globe to Globe. Every play of Shakespeare is to be performed in a language Shakespeare didn’t use. The project, based at the replica theatre on the South Bank, asserts Shakespeare’s universality in rather weird terms.

‘Shakespeare is the language which brings us together better than any other, and which reminds of our almost infinite difference, and of our strange and humbling commonality.’

Some of the choices are intriguing and apposite. The Merchant of Venice in Hebrew makes a lot of sense. And London’s Turkish community will thrill at the chance to watch Antony and Cleopatra in their native tongue. But how many play-goers are gagging to see Troilus and Cressida in Maori? Or Cymbeline in Juba Arabic, the dialect of Southern Sudan? Othello is to be performed in a language identified as ‘hip hop’. This turns out to be Chicago English with the text ‘spun out, smashed up and lyrically rewritten over original beats’. Here’s a snippet. ‘I hate the bastard, hate the Moor, I hate his rhymes, I hate his whore.’

Is this entertainment or a test of our endurance? There’s a clue in the Globe’s ticketing structure, which offers ‘a heptathlon’ of multiple seats for those with enough stamina to sit through seven doses of sur-titled Shakespeare. Having watched quite a few dramas in foreign languages I can predict what these sturdy-bottomed thesp-watchers are in for. It’s like visiting an art gallery with the lights off or having gourmet soup piped in through your arteries. You get something but not as much as you’d get if you did the thing in the normal way.

Globe to Globe is a wonderfully insane idea but I doubt if I’ll be joining the Bard-athlon. Some things are a bit too pointless even for the Olympics.

Comments