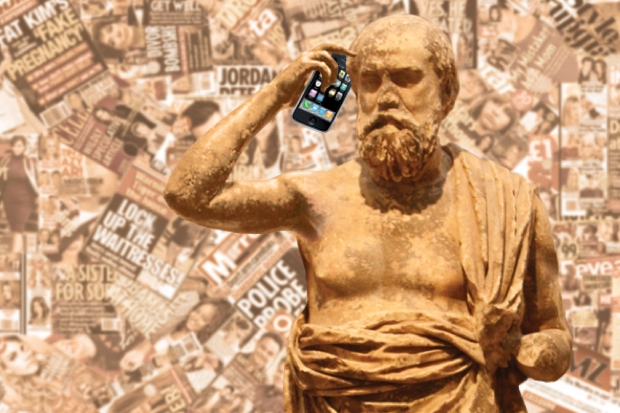

Adults, we are told, as much as children, become gibbering wrecks if deprived of their mobiles or iPhones for more than 15 seconds. The 2nd-century ad essayist Plutarch foresaw the problem.

In his essay ‘On being a busybody’, Plutarch takes a very strict line on man’s desire to be up to date on every last piece of news and gossip, especially what is ‘hot and fresh’ and, most important of all, scandalous. Joyful occasions — weddings and such like — are of no interest. Country life is even worse, ‘since they find the peace and quiet unendurable’. It is ‘adulteries, seductions, family quarrels, lawsuits’ that a man wants, or if forced to be in the country, information about whether his neighbour’s cattle have died, or his wine oxidised. It is only a good haul of disasters and difficulties that will satisfy a man, enabling him to rejoice at other people’s misfortunes (Greeks too had a word for Schadenfreude).

As a result, says Plutarch, people receiving communications are so desperate to read them that ‘they go so far as to bite through the fastenings with their teeth if their hands are too slow’; and he contrasts the behaviour of one Arulenus Rusticus, who received a letter while listening to one of Plutarch’s lectures, but refused to open it till the lecture had finished and the crowds dispersed: ‘Everyone admired the dignity of the man.’

It is here that Plutarch draws an important contrast with our own world. While man revels in other people’s disasters, he says, no one has any desire for details of his own life and troubles to be spread abroad. Here he draws a splendid parallel with men’s hatred of customs officers, who dig around in one’s personal baggage, searching for concealed goods.

One can only guess at what Plutarch would have said about today’s iPhone-maddened generation, who, however desperate they are to receive gossip and scandal about other people’s lives, are just as keen to spread the same abroad, in words and pictures, about their own.

Comments