At the age of just 21, Samuel Palmer produced one of British art’s greatest self-portraits.

At the age of just 21, Samuel Palmer produced one of British art’s greatest self-portraits. Although he is wearing the clothes of the period (1826), the face that surmounts the casually fastened soft high collar is both Romantic and modern, instantly and thrillingly bridging the gap between his century and our own. As Rachel Campbell-Johnston notes in her welcome biography, Palmer’s hair is unbrushed and he seems not to have bothered to shave: ‘It’s hardly the image you would expect from an upcoming artist at that time. He does not strike the pose of the ambitious young professional; make a bid for new clients by parading palette and brush’. This, it turns out, was part of Palmer’s problem in a career that frequently foundered on his inability to meet commercial demands. In a period when public taste was for huge and dramatic canvases that one was expected to stand back and admire, Palmer produced ‘tiny luminous squares’ which were seldom ‘larger than an open book’ and required close inspection to reveal their genius.

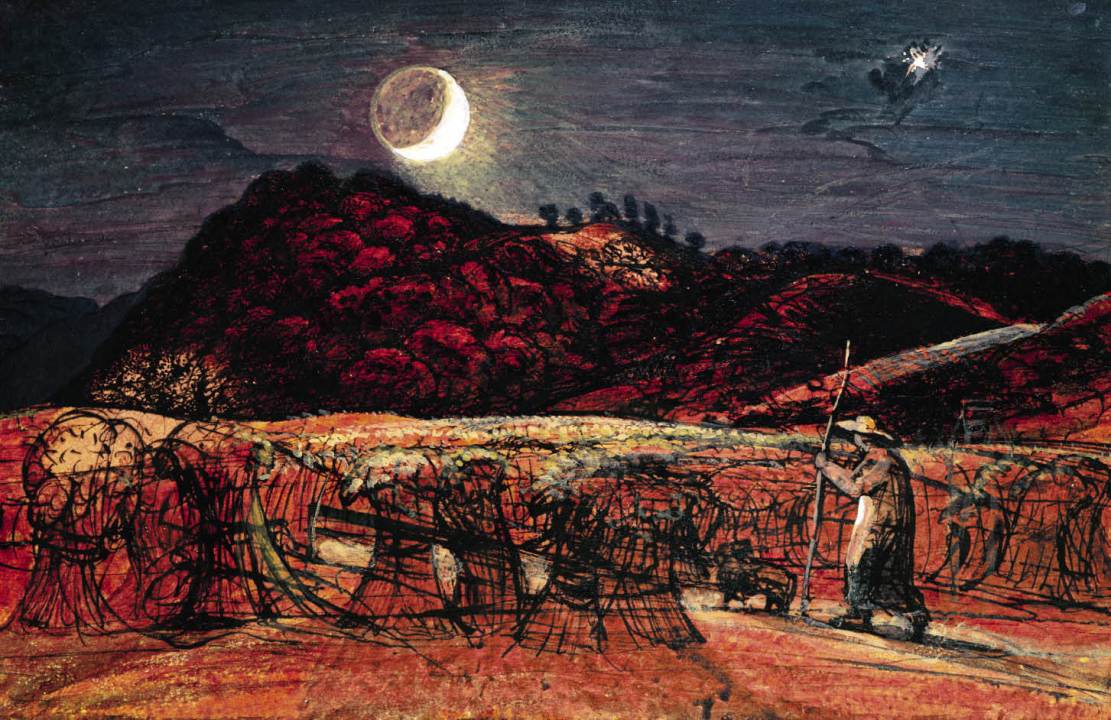

Palmer was a youthful prodigy and his finest and best-known paintings, such as ‘The Magic Apple Tree’, ‘Coming from Evening Church’, ‘The Gleaning Field’ and ‘In a Shoreham Garden’, were done in Shoreham, Kent, over a short, highly productive period when he was in his mid twenties. Many of them were never exhibited during his life but hidden away in what he called his ‘Curiosity Portfolio’. A long honeymoon spent travelling in Italy from 1837 to 1839 did not result, as he had hoped, in a new and financially successful phase in his career. Studying old masters may have taught him a little more about figure- drawing, but by the time he got back to England, public taste had long since moved on from Italy to the Orient. ‘Italy has been painted out and out,’ the Athenaeum had loftily declared, ‘and we are weary of its splendid scenes and contemptible people.’

It was now even more difficult to find buyers for his pictures, and Palmer was obliged to take pupils in order to support his family. There followed a series of disasters. He became estranged from his father-in-law, John Linnell, a close friend of his youth, and lost his only daughter when she was three. After his older son, More, in whom he had invested all his hopes, died aged 19, Palmer went into a steep decline. Increasingly slovenly in his appearance and eccentric in his behaviour, he grew apart from his socially ambitious and frequently embarrassed wife, with whom he had reluctantly moved into a hideous neo-Gothic house in the suburbs of Redhill.

Things improved a little in 1864, when at the age of 59 he received a commission from a Lincoln’s Inn solicitor with the splendid name of Leonard Rowe Valpy to produce a series of small watercolours derived from Milton’s ‘L’Allegro’ and ‘Il Penseroso’. Milton had long been one of the bookish Palmer’s literary idols, and this project occupied him for the final 17 years of his life, alongside a time-consuming and inept translation of Virgil’s Eclogues, which would be illustrated with ten etchings. In this work he was greatly assisted by his surviving son, Herbert. ‘You may, please God, be a balm to my heart,’ Palmer told Herbert when More died, ‘but I fear the odds are against it.’ Herbert, who emerges from this biography as something of a hero, overcame those odds and subsequently compiled The Life and Letters of Samuel Palmer (1892), which show him to have been both an affectionate son and a lively writer.

Palmer is often described as a visionary, and it seems odd that such radiant paintings should be the result of religious beliefs that were less ecstatic (as his chief inspiration William Blake’s were) than dour. Palmer was brought up a Nonconformist and seems to have espoused the most dismal and life-denying form of this faith. Campbell-Johnston never quite addresses the striking contrast between the Palmer who produced such joyous paintings and etchings and the one frequently hectoring people — not least his hapless children — about the straight and narrow path to God.

As well as being a wonderful painter, Palmer is revealed here as a fine writer. As long as he kept off the topic of religion, his writing is vivid, humorous and touching. Campbell-Johnson’s biography shares these traits, as when she describes a drawing of a coastal sketching expedition in which ‘the bespectacled Palmer and his bonneted wife perch on a rock like a pair of puffins while half a dozen other artists roost all round’. She also writes particularly well about the stuff of painting: materials, techniques and effects. The book could, however, have been more generously illustrated, and the source notes to Palmer’s published letters needed dates as well as page references if they were to be of any real help to the reader.

Comments