Home

Brexit exerted ever stranger effects on politics. After an eight-hour cabinet meeting, Theresa May, the Prime Minister, said she would ‘sit down’ with Jeremy Corbyn ‘to try to agree a plan’, though it ‘would have to agree the current withdrawal agreement’. The United Kingdom had been required to present a plan to a European Council summit on 10 April in order to be granted a long extension of the Article 50 process, or else leave the European Union on 12 April with no withdrawal agreement. But now Mrs May wanted a short extension, to pass a withdrawal bill before 22 May and avoid EU elections due the next day. MPs had already voted by 344 to 286 to reject the government’s withdrawal agreement for a third time, despite her promise that she would resign if they passed it. Although Boris Johnson and Jacob Rees-Mogg had changed their tune and voted with the government, the Democratic Unionist party did not; Richard Drax voted with the government and later apologised to the House for having done so. Mrs May said at that point that it was now ‘almost certain’ that Britain would have to take part in the EU elections, and that it might have ‘reached the limits’ of what parliament could achieve. Eurostar travellers were delayed when someone draped in a flag of St George set up camp all night on the roof of St Pancras station.

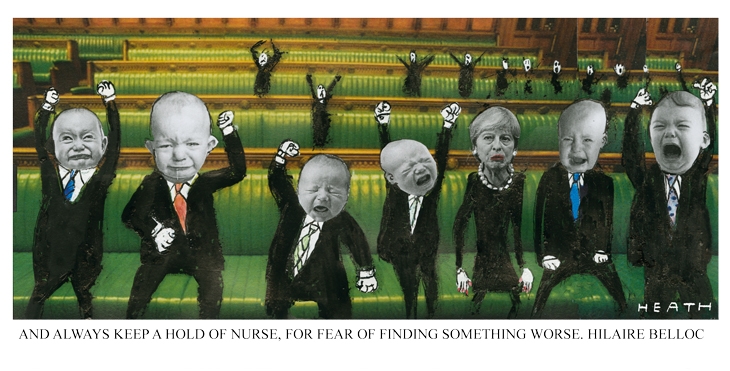

The House of Commons, embracing an amendment by Sir Oliver Letwin, had in the meantime set itself the task of giving indicative votes on Brexit. Each member, in the Aye lobby or the No lobby, according to whether their name began with A-K or L-Z, was given a ballot with eight propositions. None was passed. While they were waiting for the count, MPs approved by 441 to 105 a statutory instrument to change the date of Brexit in British law from 29 March. MPs repeated the indicative vote exercise five days later. The Speaker chose four propositions. A choice by parliament between revoking Article 50 and leaving with no deal was defeated 292 to 191 (having been defeated by 293 to 183 on 27 March). To have another referendum on any Brexit deal that was passed by parliament before its ratification was defeated 292 to 280 (295 to 268 on 27 March). A permanent customs union with the EU, tabled by Ken Clarke, was defeated 276 to 273 (271 to 265 on 27 March). UK membership of the European Free Trade Association and European Economic Area, with arrangements with the EU single market and customs union, tabled by Nick Boles, was defeated 282 to 261 (283 to 189 on 27 March). Nick Boles then resigned the Conservative whip, to sit as an independent conservative. ‘They have all been cowardly when they should have been brave,’ he said of the cabinet. ‘None of them should be prime minister after Brexit.’ The Independent Group, known as Tig, said it was becoming a political party called Change UK, and became known as Chuk, even though Heidi Allen not Chuka Umunna became its interim leader.

UK manufacturing growth reached its highest level for 13 months, boosted by stockpiling for Brexit. Debenhams made an agreement with creditors while fending off a takeover attempt by Mike Ashley of Sports Direct. A man was stabbed to death outside Clapham Common Tube station, the 22nd fatal stabbing in London this year. Sir Mick Jagger, aged 75, cancelled concerts while he underwent heart surgery.

Abroad

Volodymyr Zelensky, a TV actor who plays a schoolmaster who accidentally becomes president, gained 30 per cent of the vote in the Ukrainian elections and went through to a run-off against President Petro Poroshenko. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s party, the AKP, lost control of Ankara in local elections and was close to losing Istanbul, though the AKP challenged both results. President Abdelaziz Bouteflika of Algeria, 82, resigned in the face of demonstrations. The Pope visited Morocco.

Americans were told that they would run out of avocados in three weeks if President Donald Trump went through with his threat to close the border with Mexico. A woman accused Joe Biden, the US vice-president from 2009 to 2017, of having kissed the back of her head; another came forward saying he had rubbed noses.

Nasa was annoyed by India testing the destruction of a satellite with a missile, complaining that debris endangered the International Space Station. In the Chinese province of Henan, a small tornado blew a bouncy castle high into the air, killing two children. CSH

Comments