Home

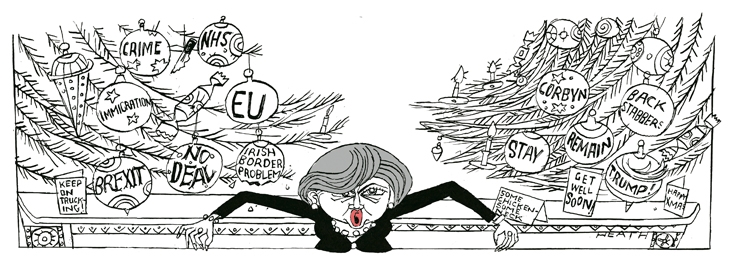

Political hobbyists speculated on the future of Brexit if the government fell, if a new Conservative leader was chosen, if a general election was called or if a second referendum was held. Debates were tabled over five days, in prospect of a Commons vote on 11 December on the withdrawal agreement from the EU to which Theresa May, the Prime Minister, had agreed. She told the Commons that it would allow Britain to negotiate, sign and ratify new trade deals from the moment it left next March (even if none could be implemented until the end of the transition period, 31 December 2020 at the earliest, or by any given date, if the backstop came into operation). A leaked letter from May’s chief Brexit adviser, Oliver Robbins, said that ‘the backstop world, even with a UK-EU customs union, is a bad outcome’. Nigel Farage left Ukip.

The government was bitten from behind by a Commons motion finding it in contempt of Parliament for failing to publish legal advice it had received on the Brexit withdrawal agreement. So it had to publish it after all. This was the consequence of ‘an humble address’, a Commons motion held to be binding, that had demanded the publication. John Bercow, the Speaker, allowed a debate on the question even though Geoffrey Cox, the Attorney General, had presented to the House a summary document, which included the information: ‘It is not possible under international law for a party to withdraw from the Agreement unilaterally.’ In his thespian baritone, Mr Cox had called the Brexit backstop universally ‘painful’ but worth a gamble. MPs also defeated the government on an amendment by Dominic Grieve allowing the Commons to propose its own plans if the government is defeated on 11 December. On another question, of whether Britain could cancel unilaterally its application to withdraw from the EU (under Article 50), the advocate general of the European Court of Justice gave the opinion that it could; the ECJ will make a ruling in its own time.

The man long known as Nick for legal reasons, whose accusations provoked investigations of prominent people for alleged paedophile crimes, was named in court, where he faced charges of perverting the course of justice, as Carl Beech, 50, a former NHS manager. Sir Terry Morgan, who became chairman of the HS2 rail project in August, learnt from the Financial Times that he was soon to be sacked by the Department for Transport because Crossrail, with which he has been associated for a decade, was nine months late and about £600 million over budget. Kate Osamor resigned as the shadow secretary of state for international development after the Times accused her of misleading the public over her knowledge of the conviction of her son for drug offences when a Haringey councillor. Her mother, Martha Osamor, was introduced to the House of Lords as a Labour peer. Dudley Zoo said that a snow leopard had been shot dead after escaping from its enclosure.

Abroad

France saw widespread rioting, the worst in Paris since 1968, during a second weekend of demonstrations by more than 100,000 protestors known as gilets jaunes from their yellow high-visibility jackets (required to be carried in every vehicle by French law). Edouard Philippe, the French prime minister, suspended large increases in diesel tax, but the protestors turned to other bones of contention.

Russia continued to delay Ukrainian ships wanting to pass through the Kerch straits into the Sea of Azov. Altria, the maker of Marlboro cigarettes, held investment talks with the Cronos Group, a Canadian cannabis producer.

The records of 500 million customers of the Starwood division of the Marriott hotel group had been hacked into since 2014, with some credit card details taken. China and America agreed not to raise import tariffs for 90 days, but further agreement proved hazy. George H.W. Bush, president of America from 1989 to 1993, during which the Gulf War ejected Saddam Hussein from Kuwait, and father of the later president George W. Bush, died aged 94. The seven-year-old presenter of Ryan’s ToyReview was said to be the highest-earner on YouTube, bringing in £17.3 million in a year.

A new right-wing party, Vox, won 12 of the 109 seats in the Andalusian parliament, robbing the Socialists of the majority they had enjoyed since 1982. President Muhammadu Buhari of Nigeria, who had been in poor health, insisted in a speech in Poland that he was neither dead nor a double. An Australian judge ruled that a New Zealand woman was not a victim of racial discrimination when her colleagues called her ‘Kiwi’. CSH

Comments