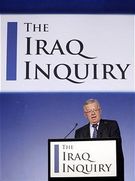

Sir John Chilcot’s Iraq inquiry has begun honing in on failures of US and British post-conflict planning. As General Sir Frederick Viggers told the inquiry, problems arose from “not having defined the ends, ways and means of how we were going to deliver this phase of the campaign.” None of this is particularly new.

Sir John Chilcot’s Iraq inquiry has begun honing in on failures of US and British post-conflict planning. As General Sir Frederick Viggers told the inquiry, problems arose from “not having defined the ends, ways and means of how we were going to deliver this phase of the campaign.” None of this is particularly new.

As further evidence is provided to the inquiry, it will become even clearer how unprepared the British state – the Government, civil service and military – were for the task at hand, and how soldiers, diplomats and development workers were expected to deliver near-miracles with limited resources, limited backing, limited security and limited public support. I was there and it was not very pretty.

While Sir John will presumably apportion blame, it’s far more important to ensure that mistakes are not made again. While we may not see carbon copies of Iraq and Afghanistan, it is also hard to imagine that future operations will not, in some ways, be similar. After all, if interventions take place in Muslim countries, it’s likely that Al Qaeda or its affiliates will try to enter the battlefield. Likely, too, that they’ll repeat the kind of insurgency tactics which have been deployed in Baghdad, Kandahar and Waziristan.

In turn, this means that Western forces must be prepared to draw on the skills and capabilities developed in this decade’s conflicts, including: the need to support and collaborate closely with indigenous forces; a requirement to undertake some form of post-conflict, or even ‘in-conflict’, reconstruction; and an ability to operate in an extremely hostile environment.

In this article for the RUSI Journal, I propose a series of changes to help prepare the British state for this enduring task. You’ve got to hope that 2010 will see progress made on these reforms.

Comments