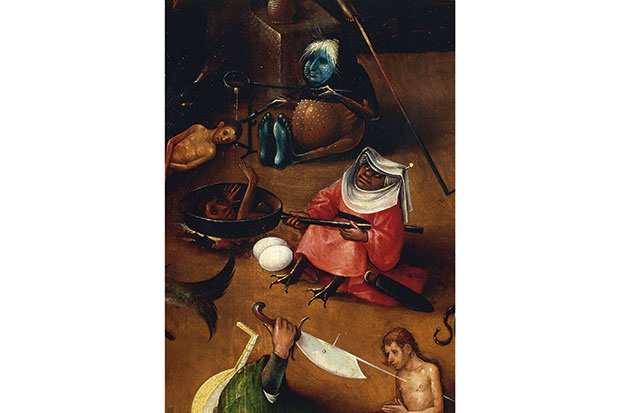

To call Nils Büttner a killjoy is perhaps a little unfair, but not very. The professor at Stuttgart’s State Academy of Art and Design has written a revisionist biography of Hieronymus Bosch: one which tells us that the Early Netherlandish painter wasn’t, as many over the centuries have suggested, the devil incarnate or Satan’s crazed representative on earth. Instead, his graphically disturbing visions of hell — infernal soups populated by hybrid monsters — were actually the product of a devoutly Catholic, medieval mind.

Bosch came from a family of painters in the town of ’s-Hertogenbosch near Antwerp and, following an orthodox education and advantageous marriage, became an important member of the local religious confraternity, the Illustrious Brethren of our Blessed Lady. This was no sociopathic recluse, but a man of civic significance; his personal life was as staid as his art was wild.

Bosch was one of few northern painters Giorgio Vasari deemed worthy of inclusion in his epochal Lives of the Artists. As Büttner observes, Bosch also counted key figures across Europe as his patrons. Philip the Handsome, King of Castile, paid 360 guilders for the 1504 triptych, ‘The Last Judgment’ (roughly the cost of two small ships). The VIP client list is proof that, however idiosyncratic they may seem to us today, these images didn’t cause outrage in Bosch’s own day. Middle Dutch literature was rich in descriptions of eternal fire and Bosch’s demonically detailed visions were rooted in the tradition of Gothic manuscript illustration.

Büttner is strong on historical context, specifically on how imagery was used by the church in the Middle Ages, through direct, visceral impact, as a means of religious instruction. The idea was to save souls by scaring the illiterate masses, who couldn’t read a Bible, about what awaited them if they lived sinfully. Bosch’s was art as pictorial sermon, one complete with strange avian creatures sprouting from human rectums.

Visions and Nightmares isn’t the most riveting read. Büttner fails to explore what relationship Bosch had with his illustrious patrons and how he ended up the painter of choice for so many: Queen Isabella of Spain, Margaret of Austria and the Venetian cardinal Domenico Grimani, to name but three. This is a pity, given that, according to Büttner’s own thesis, so much of the rest of Bosch’s life was prosaic.

It doesn’t help that the academic style is so reader-unfriendly. Admittedly, part of this is the fault of Büttner’s translator, but I lost track of how many long, impenetrable passages I had to read three times to make any sense of. Buried at the end of many such passages was a point so trite I could hardly believe it was for real. For instance: ‘The way in which Bosch used paint as a means of artistic expression was without parallel in his age.’

The book was originally published in 2012 but now appears in English to mark the 500th anniversary this month of the painter’s death. Bosch studies, though, have moved on in the intervening years: 2016 has seen two first-rate exhibitions, one this spring in ’s-Hertogenbosch, which attracted a record-breaking 400,000 visitors to a town of just 150,000 people, and another at Madrid’s Prado till mid-September. Key players in both shows were the Bosch Research and Conservation Project, a body which has been busy exposing works once attributed to Bosch as actually by his followers. The count of officially approved panel paintings now stands at 25 and, unfortunately for Büttner, two or three of the works he focuses on have, since the time of writing, been deemed to be by someone else. There’s a sense that his book is already out of date.

More frustrating, however, is the abrupt way it finishes. At just 180 pages of text, surely there was space and time for a chapter on Bosch’s legacy, and the way he has been adopted by various causes, movements and madmen over the past half-millennium. He has been dubbed an astrologer, an alchemist and a hallucinogenic drug addict. Freudians and surrealists were drawn by his nightmarish outpourings, while freeloving counterculturists in the 1960s were turned on by his naked hordes in tantric contortions. The further away we get from Bosch’s era, the more creative the interpretations of his imagery have become.

Büttner closes with the line: ‘There’s no doubt that over the last 500 years, Hieronymus Bosch has lost none of his fascination.’ It’s just a shame his book offers so few clues as to why.

Comments