I’ve just returned home from seeing Douglas Murray, Jordan Peterson and Sam Harris on stage at the O2 Arena in London before a crowd of 8,000 people. And I have to say, it was a pretty good show.

Once you’re past the bizarreness of seeing three top-flight intellectuals calmly occupying the same stage normally strutted upon by the likes of Iron Maiden or Def Leppard, it’s tempting to try to evaluate the content of the discussion, score it like a boxing match, or try to figure out which gentleman is the more brilliant or righteous. But those angles, valid as the might be, miss the larger point: namely, that deep conversation, underpinned by goodwill, delivers transformative value that can’t be obtained any other way.

Backstage an hour beforehand, I asked the event’s impresario, Travis Pangburn, what makes for a crackling dialogue: “In order for it to be a good conversation,” he answers, “the stakes have to be large, and the air has to be thick.”

He explained to the assembled journalists that when he initially suggested he could fill up a joint like the O2 with punters coming to see intellectual rock stars, people said he was crazy. Insurers even had trouble writing a line on the event because there were no precedents. “They’d ask me, ‘So what are these men doing on stage? Just talking? Really? There’s no pyrotechnics?’”

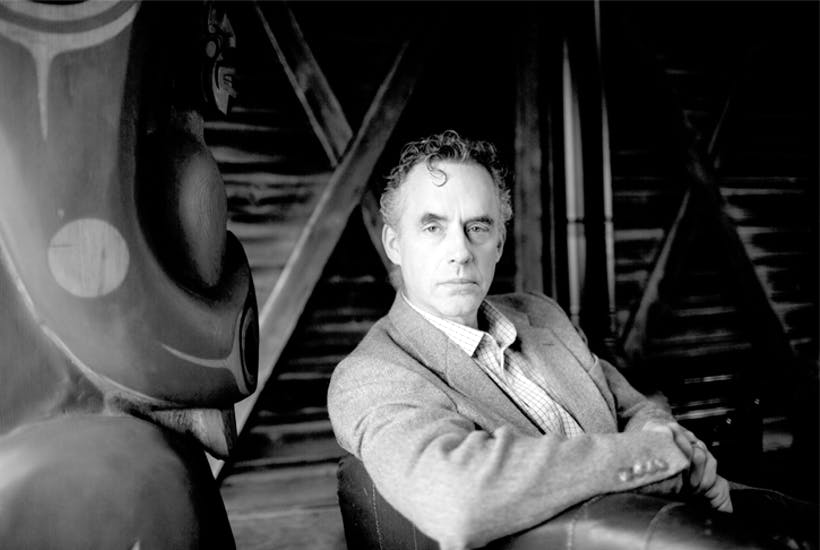

A few minutes later, Jordan Peterson strode in to the room and asked “Where should I sit?” Without waiting for an answer, he plunked himself down on a very, very low side table. It made him look like an adult sitting on a kid’s chair in a nursery school, but he was unfazed.

Deciding to front-run the journalists, I ventured: “What question isn’t being asked lately that you wish would be asked?”

He pondered it for a millisecond, then answered: “Why are so many people coming to these events?” He said it’s because they’re hungry for meaning, and because they want to bear witness to extended intellectual discussions. He believes the short, rigid interview formats favoured by the legacy media are making us all think we’re dumber than we are.

Later, I introspected about my own reason for attending, and I realised it’s because I wanted to determine why I rate (and like) Peterson more than Harris (whom I do respect, and have at times enjoyed).

By the end of the night, I’d figured it out: it’s mainly because Peterson’s cognitive reach is more flexible and expansive than Harris’s; quite simply, he apprehends more. (I’m not asserting, necessarily, that Peterson is more correct; just that Peterson, broadly speaking, is more capable of being more right about more things than Harris is.)

And indeed, onstage there were several moments when Peterson flashed his frustration at Harris for seeming either unwilling or unable to grasp certain points at the same level of analysis at which Peterson made them. Equally, there were times when Harris seemed irritated by Peterson’s speech patterns and sentence construction. It occurred to me, though, that perhaps some of the complex thoughts and ideas which Peterson aimed to express with accuracy and nuance in a “truth-seeking” spirit instead struck Harris as evasive and wishy washy.

It also looked to me like Peterson is more successful at understanding Harris’s stances than vice versa. In a recent podcast interview, another Intellectual Dark Web luminary, Eric Weinstein, opined that we all should be able to run mental emulators of other people within our own minds. From the looks of things, however, Peterson is much better at “running the Harris emulator” on his own brain than Harris is at running a Peterson emulator. Frankly, I don’t think Harris fully understands Peterson, whereas I do think Peterson gets Harris – nearly, usually – spot on (even when they disagree, and even when I think Peterson is wrong).

It occurred to me too that Peterson, amongst the denizens of the IDW, is more of a creator/visionary (as are Eric Weinstein and his brother Bret), while Harris is fundamentally more of a critic, albeit a competent one. By nature, the critic can never see what the creator sees — but he doesn’t need to in order to be constructive (that’s part of the magic power of conversation).

At their best, Harris and Peterson were feisty but not talking entirely past each other. For instance, the last exchange in the main session went like this:

Peterson: If something is deeply wise, it’s reflective of a deeper reality. Otherwise it wouldn’t be wise. So, what’s the deeper reality that something as wise as the story of Cain and Abel reflects? What’s the reality?

Harris: The landscape of mind that either takes great training, great luck, or pharmacological bombardment of the human brain to explore. There are ways to get there. There are ways to have the beatific vision…. I’ve had many experiences that if I had them in a religious context would have counted for me as evidence of the truth of my religion. But because I’ve spent a lot of time seeing the downside of that form of credulity, I have never been attempted to interpret these experiences that way.

Peterson: Try a higher dose… you’d be surprised, my friend.

Harris: Maybe that’s our next podcast.

Douglas Murray, for his part, stayed quiet for long stretches, but when he did chime in, it was always with something salient, such as this take on how contemporary secularists can be just as dogmatic (and problematic) as the conventionally faithful:

Murray: We may be in the midst of discovering that the only thing worse than religion is its absence. I mean, every day there’s a new dogma. They’re stampeding to create new religions all the time at the moment, [with] every new heresy that’s invented. And they’re not as well thought-through as past heresies. They don’t always have the bloody repercussions yet, but you can easily foresee a situation in which they do. A new religion is being created as we speak by a new generation of people who think they are non-ideological, who think they’re very rational, who think they’re past myth, who think they’re past story, who think they’re better than their ancestors and who have never bothered to even study their ancestors.

The full video, Travis Pangburn apprised, will be released in a few weeks. Some grumble that it’s not being released right away, but I agree with Bret Weinstein, who moderated the first Peterson-Harris conversation some days ago in Vancouver: it’s better if the people in the room discuss and decide what they saw before the experience gets shared, and bandied about, with people who weren’t in attendance on the night. Physical presence and the feel of the venue contain information that’s lost on video tape.

Ultimately, the one thing everyone on stage was in concurrence about was the matchless power of conversation for elucidating truth. As Peterson put it: “Through discourse, we engender the world.” Harris chose plainer words: “Primates like us having conversations. This is the best game in town. And it has always been so.”

Agreed. And if TED and its 17-minute pontifications represented the primary transmission vector of ideas and intellectual nutrition for the last 10 years, the next decade will be marked by freewheeling, freethinking, free-form conversations.

What a great thing that is.

Comments