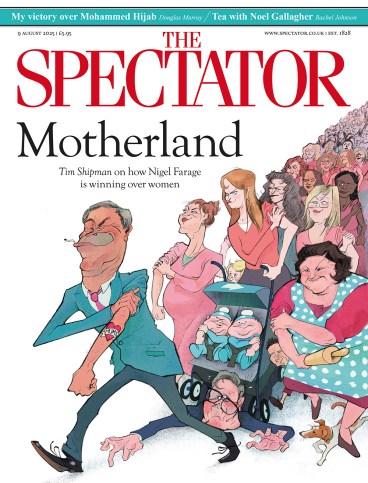

In what may be the only joke in this book – it is hard to tell, because quite often reading it I started to believe the whole thing was an elaborate parody – Samuel Miller McDonald begins his acknowledgements by expressing his ‘infinite thanks’ to his editors (he merits six of them) on the grounds that ‘no work can be good without good editors’. Apparently some works can’t be good even with good editors – unless the author is trying to tell us that his, like his oeuvre, weren’t especially good at all.

Progress is a prolix, tendentious book, radiating self-regard, arrogance and flannel. One irritation (which became like waiting to hear the next drip of a tap) is that virtually every name cited comes with a prefixed label, such as ‘historian’, ‘economist’, ‘geographer’ or, when all else fails, ‘scholar’. A notable example is ‘French aristocrat and military officer Marquis de Lafayette’. It is but one aspect of the absence of literary style, which makes one wonder whether the phalanx of editors expected anyone to read the book. I am reluctant to deploy the old joke about my having read it so you don’t have to, but believe me, you really don’t.

McDonald advances an argument that since the dawn of time mankind has been on a course of ecological destruction in the name of progress. Because he is manifestly a very special scholar of this process, and has very special ideas of what to do about it, he invents his own special language to describe what has happened, and what is still happening, to ensure that ‘progress’ destroys our planet. He writes exhaustively about ‘parasitism’, which he defines as when ‘one organism captures energy from another to the other’s detriment’. ‘Energy capture’ becomes one of his catchphrases, used when he wants to describe the exploitation (usually by white capitalists) of poorer people (usually those of colour).

The reader soon feels that the author is spending hours shouting at him or her, railing against the existence of human nature and the events of the past. His writing, when he gets worked up, is barely comprehensible:

Contiguous parasitism relies on a particular form of energy capture in which primarily centralised bureaucracies organise armies and industries to extract energy from both indigenous human populations and native ecological systems in their immediate vicinity.

Where were his editors when he needed them?

McDonald lays out his core beliefs in an introduction that sets the standards of the book for verbosity, dismal style and aggressive assertion. Progress? Rubbish, he argues. Poverty is not falling, it’s rising. Freedom is not expanding, it’s contracting. Liberalism? A means of legitimising various parasitic activities. He concedes that longevity is increasing: but even if it is, does that entail ‘more positive outcomes’? At that point I feared he was about to advocate mass suicide.

He voices all the current obsessions beyond the hell of climate change – the wickedness of slavery (I have yet to meet anyone in favour of it, so we might consider that argument as having been won, but in any case McDonald does not regard abolition as ‘evidence of a long moral arc’); the odiousness of empire and colonisation; and the general vileness of white men, especially capitalists. America is the ultimate villain – not just keen on slaves but horrid to the indigenous people, even including that nice Abe Lincoln. (The author presents as a self-hating American.) The Whig interpretation of history this is not: the world turns out to have been appalling throughout its existence, and things are only getting worse. To be fair, McDonald is pretty rude about Stalin and Mao, less so about Lenin, and, perhaps to establish his credentials with a certain sort of reader, has the obligatory swipe at Margaret Thatcher.

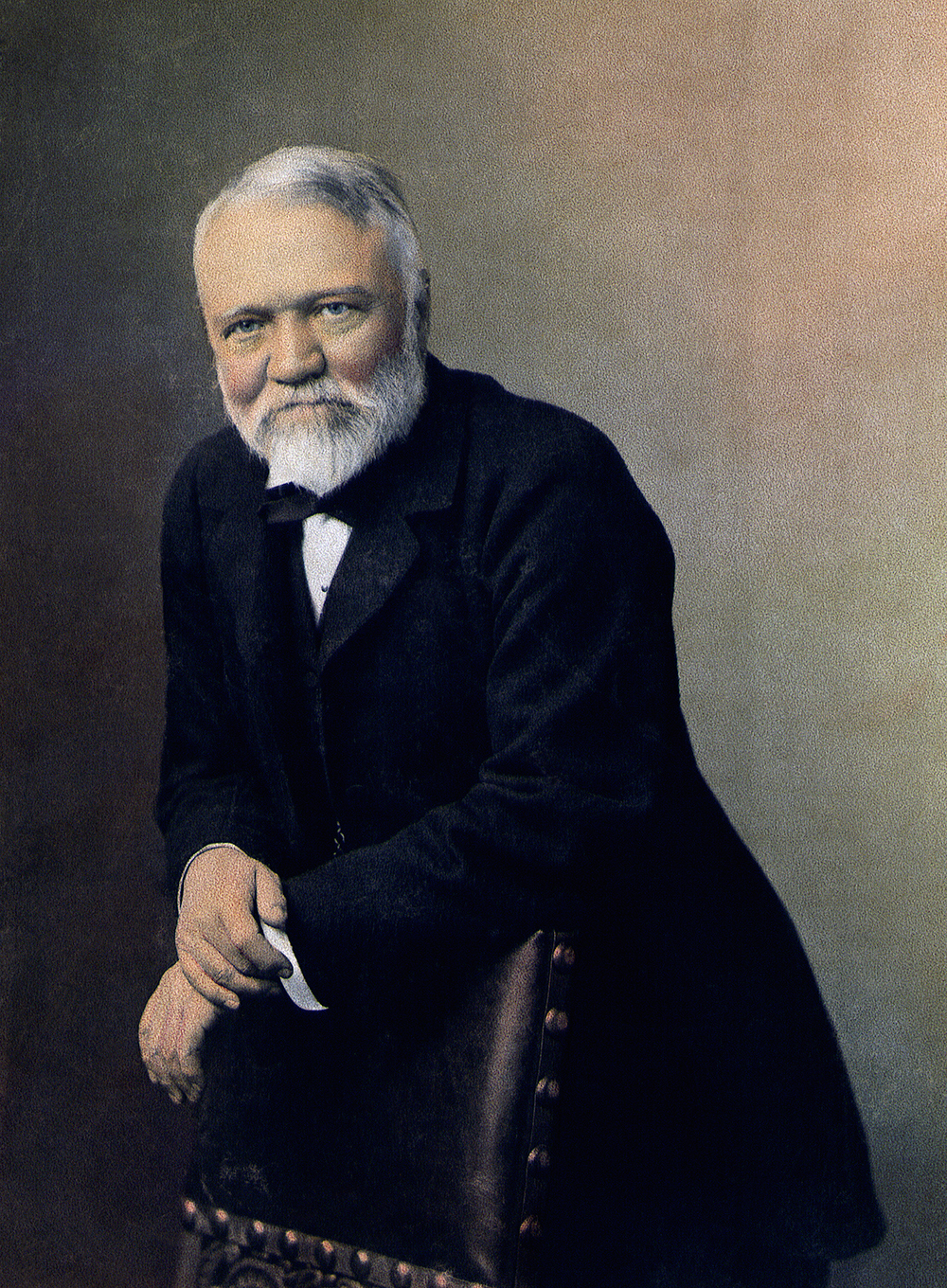

Occasionally, the assertions become rants and are simply absurd. He says of Andrew Carnegie that he became rich ‘in part by imposing extreme labour practices on workers, forcing employees to toil 12 hours a day seven days per week for poverty-level wages’. Forcing them? Were they enslaved? And where is Carnegie the man who gave away 90 per cent of his fortune?

Macdonald goes even more off the rails with a bizarre attack on King Edward VIII, who certainly did enjoy the company of leading Nazis; but because McDonald and the concept of constitutional monarchy are strangers to each other, he does not grasp that the King was powerless when the Germans reoccupied the Rhineland in March 1936, and that the fault for any inaction was Stanley Baldwin’s. Similarly, there was nothing the King could have done about Oswald Mosley; but McDonald’s detestation of royalties and aristocrats doesn’t allow such details to get in the way. He also seems unaware that the British state abhorred the Duke of Saxe Coburg and Gotha even more than he does, and took away his Dukedom of Albany in 1919 for fighting against Britain in the Great War; but again, details, details.

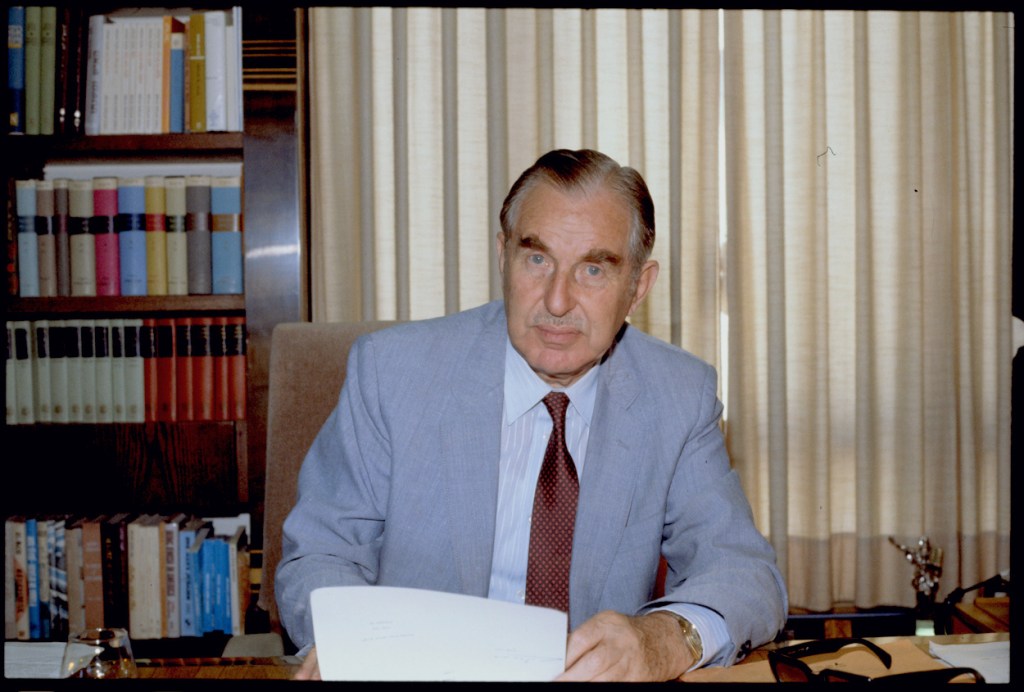

Apparently ‘intensive fossil energy capture’ by other nations was what defeated Hitler and Mussolini, not the vast firepower of the hated Americans, the hated British Empire and their allies. McDonald also assaults Harold Macmillan, who might usually ask for it; but in this case it is for his 1957 ‘never had it so good’ speech, in which he also warned that a Labour government might bring ‘rationing, shortages, inflation and one crisis after another’. The author, who is a geographer, yet one who clearly imagines he has an almost omniscient grasp of history, calls this ‘a strange and ahistorical assertion’. He seems unaware that those pestilences had featured in the previous Labour government, and thus Macmillan was entirely justified in warning his audience that they might return.

I could go on listing the absurdities, but it is enough to express amazement that William Collins felt it was a good idea to publish this book by a man who comes to resemble a pub bore. It ends with a long, pie-in-the-sky, rambling set of thoughts about how the future might be better. I read them once and could not understand what this visionary author was saying. I tried to read them again and lost the will to live. If you really want to punish yourself, you can try too.

Comments