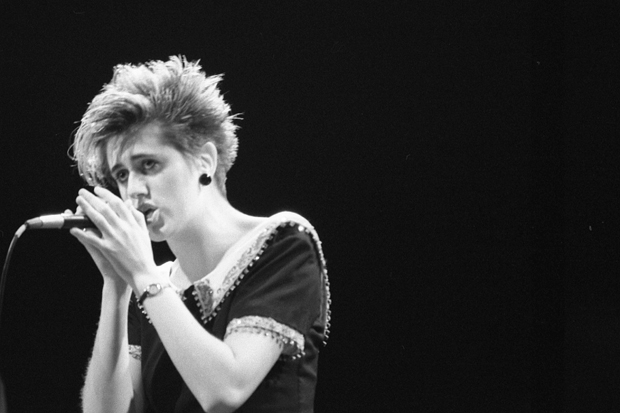

Look up Tracey Thorn’s live performances with Everything But The Girl or Massive Attack on You Tube and you’ll find the comments posted beneath it full of praise for the liquid melancholy in her lovely voice. The simple sound of air passing from her lungs, across her larynx and out of her lips in the 1990s is ‘sexy’, ‘soulful’, ‘classy’ and, most often, ‘perfect’. And don’t get her wrong; she’s chuffed that people like the noise she makes. But she frets about how much this ‘disembodied voice’ has to do with the rest of Tracey Thorn: the introvert with the ‘suburban’ speaking voice.

The anxieties she has built up around the ideally effortless act of singing have prevented her from performing live since the last (and probably final) EBTG album was released in 2000. So this thoughtful book investigating every aspect of the art — mostly focused on pop, but touching all genres — tends to focus on difficulties faced by anybody seeking to use and transcend the human body as an instrument.

Taking a practical iconoclast’s pleasure in exposing the biological and technological realities lurking beneath the romantic image of the professional singer, Thorn describes the daily battle fought against enemies like phlegm and dodgy stage trousers. Quoting from the tenor Ian Bostridge’s A Singer’s Notebook (2011), she reminds us that the primary function of our vocal mechanism is not the one with which we most strongly associate it, but as one of several lines of defence against choking. From Bostridge she learns that hitting the high notes ‘is actually about persuading the body that one is not about to swallow as one reaches for the skies’.

Yet most of us start our lives cradled by crooning adults and quickly enter a world of nurseries and primary schools where singing — for fun, to learn and form social bonds — is the norm. Becoming a mother of three after years as a professional singer, Thorn was struck by how, in this context, singing was ‘not about how special you were, but about how much you could fit in’.

This blissful harmonic world breaks down with the evolution of self-consciousness. There’s a point beyond which singing will, in most public contexts, single you out. Give people the impression you think you have something special to offer. That’s what makes Thorn so uncomfortable. Like her heroine, Dusty Springfield, she has a very English embarrassment around what other people might think she thinks about herself. Or the intimate access to her soul they think she’s selling.

Readers of her funny 2013 memoir Bedsit Disco Queen will remember that it was punk that turned her on to music when she was 14 and she still harbours the punk’s suspicion of the effort and artifice inherent in ‘proper singing’. Finding herself in possession of a conventionally beautiful, jazzy voice bothered her. She winced at the fakery of vibrato and the extended Americanised vowels she knows she’s used. And yet — alongside the ‘authentic’ growls and sneers of artists like Bob Dylan and Tom Waits — she thrills at the vocal acrobatics of Whitney Houston and Rufus Wainwright and gives a spirited defence of aspiring artists brave enough to step out in front of the crowds on The X Factor.

I sang in pubs to supplement my student grant in the mid-1990s and can relate entirely to her intense awkwardness and personal jeopardy. Singing popular music is like drinking: your deepest secrets might slip out without your permission. Or other people might assume that’s what’s happening, when the truth is that musical emotion can distort your ‘real’ self as much as alcohol, swinging moods and ideas out of proportion or on tangents. The craving for release is in constant conflict with the fear of it. No wonder so many singers also drink: Thorn used wine and beta-blockers to get herself on stage.

A hypnotist attempted to cure her stage fright and her response was as English as her problem. She followed the hypnotist’s instructions while unable to switch off the ‘running commentary of sarcastic rejoinders’ inside her head. Then politely assured the woman she felt better when she didn’t.

If she could work on a disguise, then I’d recommend busking, which I continued to enjoy long after my final pub performance left me curled in an excruciated rictus around my guitar like a dying woodlouse. In the anonymity of a subway (and some have incredible acoustics) nobody has time for expectations or close scrutiny. If people linger to hear the end of a song, they generally do it respectfully around a corner. So you can just let rip. When it sounds good the money tumbles in and when it goes wrong your witnesses have dispersed in seconds. With the possible exception of the time a drunken businessman urinated at length against the wall opposite me, I preferred every second I spent singing underground to those spent singing for more stationary audiences at street level.

Still, I doubt you’ll see Thorn and her guitar in a Tube station any time soon, and it’s rather refreshing to read this kind of book about a problem that isn’t tidily resolved at the end. I’m sure she will be pleased to hear that makes it feel more authentic. While fans will be sorry to hear her stage fright retains its grip, Thorn hasn’t given up on singing. Her book is bursting with the joy it brings her. She’s released three great solo albums over the past 15 years and hopes to continue working in the privacy of the studio, signing off as a woman still singing: ‘Just for the sake of it; because I can, and because I want to.’

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £14.99 Tel: 08430 600033

Comments