When I was at school, I remember the art teacher returning incensed from a trip to London during which he’d taken a group of seniors to the Tate Gallery. The particular object of his ire was what he described as ‘a pile of blankets’ by Barry Flanagan. He could not accept that this was a legitimate work of art, and, in a state of raging mischief, he’d grouped his school party around the thing in question and surreptitiously changed the order of the blankets. This subversive act was intended not only to relieve his feelings but also to prove the falseness of the work. If it could be fundamentally changed without anyone noticing, it was — to his mind at least — undeniably bogus. I assume it was pile ‘3 ’68’, purchased by the Tate in 1973, that provoked this outraged response, and which now forms part of the exhibition of Flanagan’s early works at Tate Britain.

How would Barry Flanagan (1941–2009) have responded to the spirited intervention of a furious art teacher? I can’t imagine that he would approve. Although he had a highly developed sense of humour and the reputation of being a joker, Flanagan was intensely serious about his work. The pile sculpture was not haphazard but carefully planned. Each of the five pieces of ready-dyed hessian was stitched by Flanagan so that it would keep its exact shape in the pile, and each was numbered with its position. From the bottom to the top the colours were arranged thus: gingery cinnamon, pinky cinnamon, pink, olive green and turquoise. Furthermore, Flanagan left meticulous instructions about how the works should be installed in a domestic or gallery setting. Nothing, apparently, was left to chance.

The hessian stack is in the second (and best) room of the Tate’s show, which contains such other important early Flanagans as the filled sacking shapes with unreadable names. But there is an air of melancholy seriousness hanging like a pall over the galleries, as if with the departure of their creator, some of the life and sparkle has gone out of his work.

There were only a couple of other visitors when I was there (in stark contrast to the Leonardo and Vermeer shows recently reviewed), and perhaps Flanagan’s early work — before he got going on his great late theme of cavorting bronze hares — is too esoteric for popular consumption. Certainly its intellectual underpinning is not easy to explain, being much concerned with ’Pataphysics, an all-embracing philosophy derived from the writer Alfred Jarry and perhaps loosely defined as the science of imaginary solutions examining the laws governing exceptions in a universe of total hallucinations. In this exhibition we see Flanagan in his work and thought constantly pushing the boundaries: it may not make for easy viewing, but it’s certainly provocative.

This year is Josef Herman’s centenary, and to mark the event the Ben Uri Gallery, the London Jewish Museum of Art, has mounted a remarkable exhibition of his early work — or what’s left of it. Born in Warsaw, Herman left Poland for Belgium in 1938, and Belgium for France and then Great Britain in 1940. After a bit of shunting, he ended up in Glasgow for a few years, where he began to establish himself as an artist. Very little was saved from his earliest work in Europe, and there are only a couple of drawings here and a very odd painting of a woman as a sort of cornucopia from the Belgium period.

In 1942, Herman learnt through the Red Cross that his entire family had perished in the Warsaw Ghetto. He had already begun an intensely nostalgic and deeply felt commemoration of his native city in the sequence of drawings collectively entitled ‘A Memory of Memories’, and this remarkable series came to enshrine the horrors and joys of those lost years.

Herman’s great strength was in his drawing, and if his paintings can be dark and lowering, his range of watercolour and gouache combined with a declarative ink line put his works on paper in the front rank of the art of this period. He developed in particular a way of using wash over ink that softened the bite of the line and added depth and warmth.

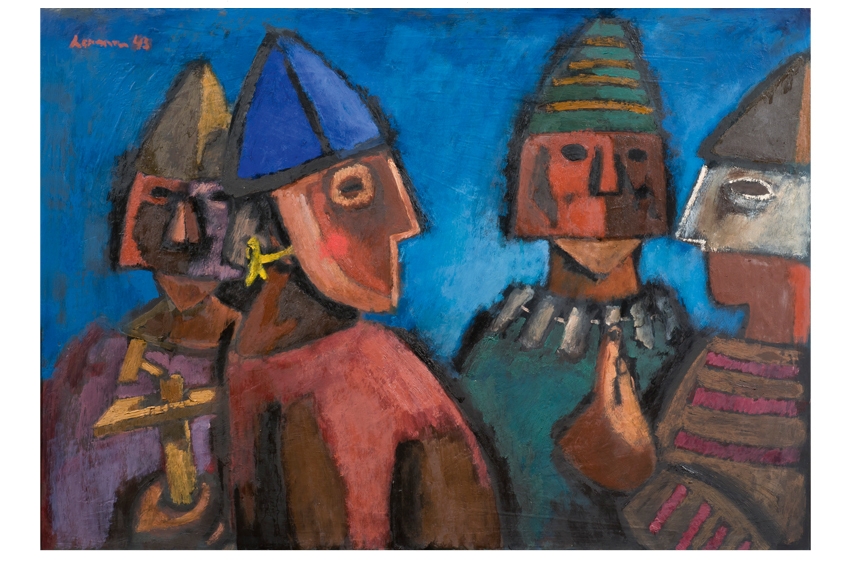

Most of the exhibits date from his Glasgow years (1940–44) and range from completely unfamiliar gouache portraits of unidentified men, done in the Polish Refugee Centre in Norwood before he was discharged and allowed to return to Glasgow, and painted with brushes made from his own hair, materials being so scarce, to a richly coloured oil painting of 1943 entitled ‘Purimspiele’ that shows the influence of African tribal sculpture of which Herman was to become such a renowned expert and collector.

There are so many beautiful and moving works here I can only urge you to see the show for yourself. Herman died in 2000 and I had the privilege of knowing him for some years, yet this early work still comes as a revelation: a fascinating glimpse of the roots that fed his later work in Wales, Suffolk and London.

At the Whitechapel Gallery is an in-focus exhibition devoted to Mark Rothko and his relationship with England and English artists, and celebrating the 50th anniversary of his first exhibition in this country, mounted in 1961 at the Whitechapel by its visionary director, Bryan Robertson. The Tate has lent a painting, Rothko’s luminous and magisterial ‘Light Red Over Black’, 1957 (see page 35), and the interested viewer is encouraged to recline on a bean bag and listen to recorded interviews about Rothko and the 1961 show.

In a taped compilation of more than an hour’s duration, you can hear the voices of artists John Hoyland, Paul Feiler, Patrick Heron and William Turnbull, together with Peter Lanyon’s widow Sheila and the art critic Tom Rosenthal. There are displays of letters from and to Rothko and evocative black-and-white installation shots of the Whitechapel in the Sixties filled with young visitors. I ran out of time and hope to return: this is an unparalleled chance to be quietly intimate with a Rothko painting and at the same time partake of oral history not usually so readily available to the public.

Comments