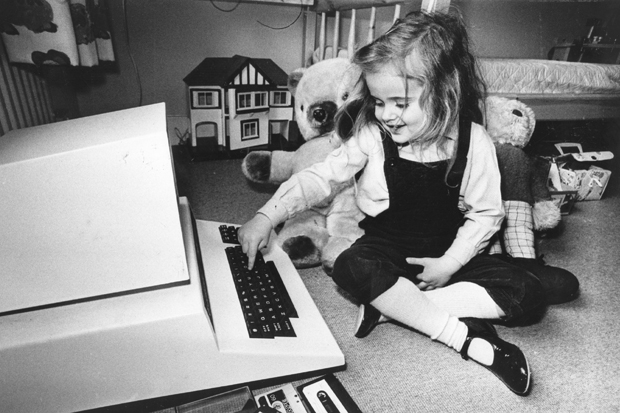

My first memory of a computer is of a hulking Acorn PC that dominated a corner of my primary school classroom. I remember crafting a story about ghosts on the beige keyboard before saving it to a floppy disk, which was filed away by the teacher for safekeeping. That was in 1995, and washing machines now easily outpower that Acorn. Yet it’s not only the gadgets in our schools and colleges that have advanced as tablets, interactive whiteboards and internal mail systems make relics of blackboards and personal planners. From September, Information and Communications Technology classes (ICT) will be replaced with Computing as part of an initiative to teach children how to create their own programs, instead of just learning to use other people’s.

Teaching pupils from the age of five to write simple algorithms and helping older pupils to learn programming languages is part of what Michael Gove, in October 2012, claimed was what Britain needs in order to ‘produce the next Sir Tim Berners-Lee — creator of the internet’. The former secretary of state for education may have been left red-faced (Berners-Lee invented the world wide web, not the internet) but the dramatic amendments to the curriculum have been hailed by many as essential to turning around the country’s technological fortunes.

In a speech in 2011, Google’s CEO Eric Schmidt criticised the British education system’s lack of focus on computer science, saying we were throwing away our ‘great computing heritage’. We may have invented photography, TV and computers, but Britons fail to dominate in those fields of technology now. What’s needed is to reignite children’s passion for science, maths and engineering.

I recently attended a Bermotech summer camp, where children and teenagers between nine and 15 were learning how to develop their own iPhone apps, and was struck by how quickly these bright young things picked up commands. Until the camp, their programming was largely self-taught. They’d watched YouTube tutorials and downloaded free programs in an effort to learn the basics, and they were clearly thrilled to have some proper instruction at last.

Providing coding lessons in school has a real purpose. There’s little point denying that an in-depth knowledge of computing would serve young people well when they enter the job market. Britain will need 750,000 skilled digital workers by 2017, according to research, and failing to bridge the skills gap could cost us up to £2 billion annually. Steve Beswick, director of education at Microsoft UK, estimates that between 80 and 90 per cent of jobs require some computing knowledge, and that is set to rise. ‘We need to get to the point where people coming out of education can fill those jobs,’ he says. ‘Across the IT industry, it’s our responsibility to help to close that gap.’

Countrywide, schools are already making changes ahead of September’s new syllabus. Barrow Hills School in Surrey recently equipped pupils and teachers with Samsung tablets in place of exercise books, journals, textbooks and calculators, and London’s Henwick Primary School already instructs its pupils how to create their own computer games, quizzes and short animations.

It’s not just about the pupils. Some teachers are understandably nervous about teaching skills which they have not fully mastered. Yet this isn’t such a barrier as it may appear, according to Henwick’s ICT co-ordinator Claire Lotriet. ‘Most of us have never been taught computer science,’ she says. ‘If a teacher is worried the children are more confident in using technology, it’s worth remembering they may be more familiar, but they may not always know how to channel that into something useful.’

Ah yes. Parents may question whether fiddling around creating a computer game can be viewed as ‘useful’, but Gove wasn’t wrong when he said that the way ICT had been taught was ‘harmful, boring and irrelevant’. Encouraging children to think logically by experimenting with new tools and processes must be better than boring them to tears with lessons in how to create a spreadsheet. A renewed focus on internet safety and online behaviour is another crucial element in equipping them to navigate lives that will be documented and mapped online.

Of course, showing a five-year-old how to make apps and websites step by step won’t necessarily turn them into the next Bill Gates or Steve Jobs. But given the extent to which technology has changed, it’s high time that the way we taught it caught up.

Comments