A near-perfect rendition of Schubert’s ‘Impromptus’ rings out of the music room’s colonial-era windows, the sound carrying all through the school’s pristine grounds. Even in India, a country famed for its sharp inequalities, there are few places where privilege is so obvious. Set in the foothills of the Himalayas, the Doon School, a private boarding school for boys aged 12 to 18, is probably India’s most elite institution.

A short walk away from the school’s main gate, children live in slums plagued by dengue fever. But here you’ll find a campus which last year won a Unesco award for cultural heritage conservation, one equipped with its very own hospital. Although the school rejects the label, there’s a good reason that many describe it as the ‘Eton of India’. Here, heirs to business empires brush shoulders with the sons of India’s political elite. Their names are put down for the school as soon as they’re born, leading to admission tests which are held in seven cities.

Founded by an Indian lawyer in 1935, the Doon School’s mission is clear and unashamedly elitist. The words of the first headmaster, Arthur E. Foot — a former Eton ‘beak’ and a relative of former Labour party leader Michael Foot — are inscribed on the wall of the foyer. The school will create an ‘aristocracy of service’ to lead a free, democratic and secular India.

‘There are very few schools in the world that have set themselves that kind of mission and have actually achieved it’, says Matthew Raggett, the current headmaster and also a Briton.

From politics, industry and banking to journalism and the military, the school’s alumni have left their mark on modern India. In the 1990s the Economist reported that after Harvard Business School, the Doon School’s alumni network was the strongest in the world. The ‘Doscos’, as old boys are known, go on to dominate public life.

The Times of India, India Today, the Hindustan Times and key Indian news channels have all been led by Doscos. Two key figures of South Asian literature, Vikram Seth and Amitav Ghosh, were editors of the school paper, the Doon Weekly. Seven generals went to Doon, plus a handful of air marshals and admirals for good measure. The career of world-famous sculptor Sir Anish Kapoor, who designed the Orbit Tower at London’s Olympic Park, can be traced back to the school’s art department.

But the school’s most famous alumnus was former Indian prime minister Rajiv Gandhi. When he unexpectedly came to power in 1984, he rallied a group of his old school chums to lead the country. Together they became known as the ‘Doon Cabinet’.

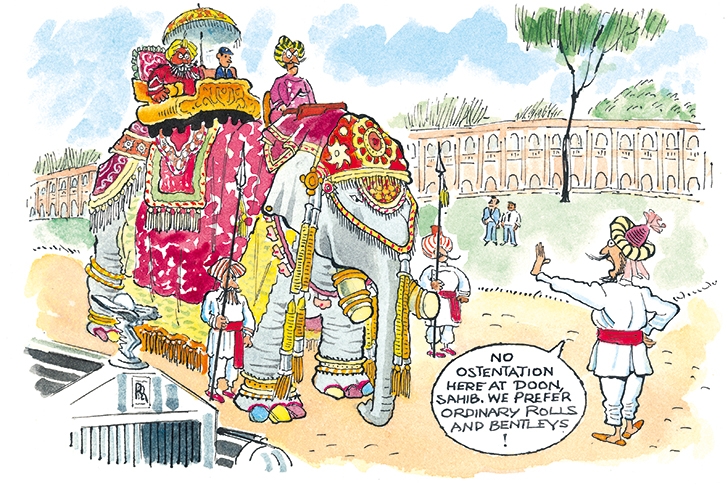

Though they may go on to great things, during their time at the Doon, boys lead a spartan existence. ‘Back in the 1930s, a Maharaja’s son came to the school on an elephant with his whole royal entourage,’ says the deputy head master. ‘They had to tell him to leave everything behind. Equality is important here.’

The school ethos centres around four values: egalitarianism, secularism, service and democracy. In many ways, these values reflect the founding ideals of the Indian National Congress party, which at the school’s formation was the dominant political force in the country.

In the dying days of the British Raj it was thought that if India and the new Indian elite did not hold true to these ideals, the nation would disintegrate. So these values are hammered into the boys at every turn.

Each student gets one locker and a row of hooks. Clothing is all identical — right down to the football boots. At neighbouring schools it’s not unheard of for boys to bribe guards to bring in drugs and prostitutes. Doon, by contrast, is a completely cashless society.

On my tour, the teachers proudly point towards a large airless dorm room with 20 beds arranged in rows. Several boys lie across their mattresses, exhausted in the stifling midday humidity.

The deputy tells me: ‘Unlike other private boarding schools we don’t give our students a luxurious time… It’s character-building.’

Of the school’s ten headmasters, five have been British — a surprising statistic at a school which serves as a training ground for the post-colonial elite. Matthew Raggett was appointed last year and he has an ambitious agenda.

‘The irony of being the only British guy in the school presiding over the celebrations for Indian Independence Day was just hilarious,’ he says.

Silhouetted against the croquet lawn, the new headmaster serves Twinings tea and samosas. Though dressed for the weather in cargo shorts, he strikes an impressive figure as he sits on his veranda and talks candidly about the school’s past successes and current flaws.

‘It’s difficult to take the elitism out of the kids when some of them can go home to so much luxury,’ he says. ‘I think what they do appreciate is that an air of entitlement isn’t appealing.

‘There are things called “favours” here,’ he continues. ‘Older boys ask younger boys to collect a morning snack. Collect my football boots. Come and give me a massage during the swimming competition. I’ve seen it.’

‘There’s a notion here that as a prefect you get “favours” done for you, and you can administer punishments, without really understanding what that says about your leadership position. That needs to change.

‘It’s the abuse of power, and the imbalance of power that’s not right. And it’s understanding that. But again it’s difficult. Because we’re in a culture which is so servant-based.’

‘This is a school for the future leaders of India.’ Raggett gestures behind him. ‘Outside that wall, this is still a country that operates on power and prestige.’

Given the country’s huge population, India’s education system relies heavily on exam performance. With their futures hanging on as little as half a mark, many students will spend any free time they have cramming in tutoring centres.

The result, says Raggett, is a tendency for Indian students to be strong at rote learning and regurgitating information, but weak in many other respects. This, he believes, is a huge shame.

‘Being a new democracy there’s a culture of good argument here; students have an opinion or thought on just about everything. And in six years’ time, we’ll have a different curriculum which will lead to critical thinking… and a recognition that the world isn’t black and white. ’

Comments