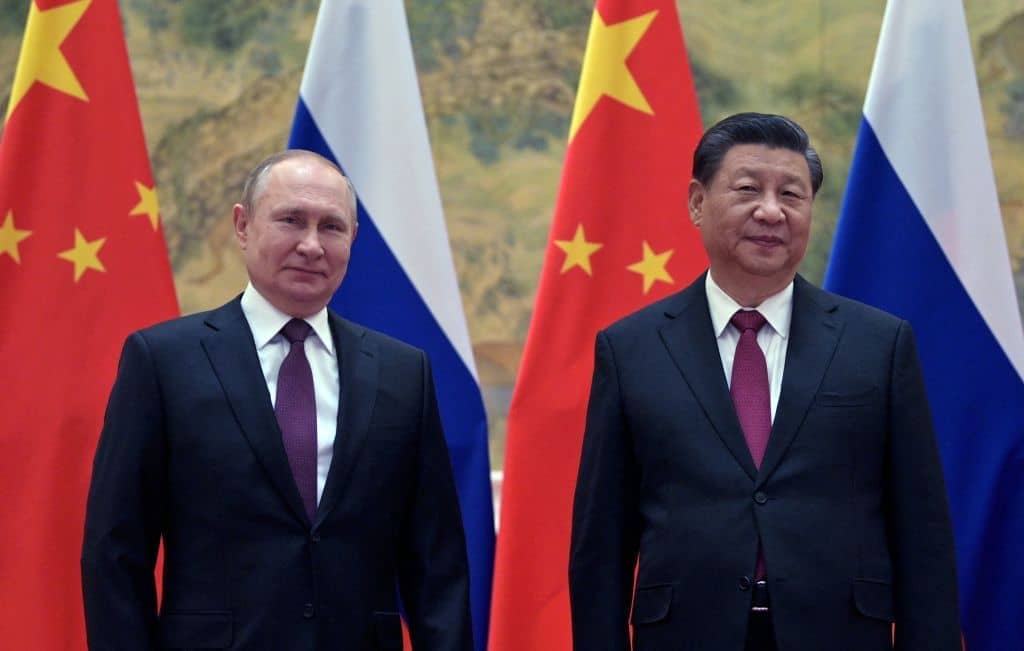

Vladimir Putin very rarely travels abroad these days – and Xi Jinping has not met a foreign leader in person for almost two years. Yet there they were together, just before the opening of the Beijing Olympics, hailing their and their nations’ friendship and concluding $117 billion in oil and gas deals. Although they themselves avoid the word, can we yet talk of a Sino-Russian alliance? Not quite: there’s more here than meets the eye.

Certainly the focus was on amity and common interests. This had been signalled in the lead-up to the summit. Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi said that Moscow’s security concerns about Nato were ‘legitimate’ and needed to be ‘taken seriously and addressed.’

At Monday’s United Nations Security Council meeting, China backed Moscow’s unsuccessful bid to have a discussion of the Ukraine crisis held behind closed doors, deploring Washington’s ‘megaphone diplomacy.’

On Thursday, Putin reciprocated, extolling this ‘close and coinciding approaches to solving global and regional issues’, and taking a swipe at the US-led diplomatic boycott of the Beijing Olympics in protest at China’s human rights record as a ‘fundamentally wrong’ attempt ‘by a number of countries to politicise sports for their selfish interests.’

Russia currently needs China more than the other way round, and Beijing knows it

It was thus no surprise that Putin and Xi rhapsodised about their ‘unprecedented’ ties, while calling on the West to abandon attempts to undermine the ‘sovereignty’ of other nations – in other words, to weigh in on what Putin may be doing with the opposition or Xi with the Uighurs. In a bit of mutual backscratching, Russia reaffirmed its support for China over Taiwan, and although China was less explicit over Crimea and Ukraine, it joined the Russians in calling for an end to Nato expansion.

With what under other circumstances might have looked deliberately tongue-in-cheek, they affirmed that they were the real defenders of ‘the real spirit of democracy’ and upheld the notion of the protection of human rights, but ‘in accordance with the specific situation in each country and the needs of its population.’

On one level, of course Moscow and Beijing see eye to eye. Moscow is cultivating a rich and secure trade partner, not least as a hedge in case of further western sanctions. Beijing wants cheap, reliable energy and primary materials to feed its strong, but potentially overheating economy.

Moscow mistrusts and fears what it regards as US ‘unipolar’ hegemony, and feels it is pushing back against creeping attempts to constrain and control it. Beijing is feeling less directly threatened, but is no less determined to assert ‘multipolarity’ against American attempts to define the world order.

Yet there are also distinct limitations to this relationship.

Russia currently needs China more than the other way round, and Beijing knows it. When the two countries signed a $400 billion gas deal in 2014, for example, at a time when Russia needed a deal for political and economic reasons, Beijing leveraged this ruthlessly: as Putin himself ruefully admitted at the time, ‘our Chinese friends are difficult, hard negotiators.’

Secondly, this is an ‘alliance’ or friendship that is primarily economic, political and performative. Despite some recent joint military exercises – that were as much as anything else precisely to warn and worry the West – there is no sense that either has any intention of joining a shooting or even economic war for the other.

Any escalation in Ukraine, for example, will trigger further western actions against Russia, and carries the risk that Chinese banks and firms could find themselves caught by secondary sanctions. Besides, China has its own interests in play, not least as Ukraine is its main corn supplier.

This goes both ways. If China’s claims to Taiwan leads to a military confrontation, one in which the United States is likely to be involved, then there is no sense that Moscow would do more than cheer Beijing on from the side-lines.

Putin and Xi will gladly cooperate on issues of mutual advantage, and talk it up in a way that they know worries and distracts Washington. But meanwhile, Russia’s security agencies are warning of greater Chinese espionage and hacking, and Beijing is investing in Ukraine at an unprecedented level.

Both men understand that this is a pragmatic, post-ideological age, in which all nations are at once competitors and interdependent. According to Putin, ‘the Russia-China relationship is an example of 21st-century international relations,’ and to be honest he is probably right.

Comments