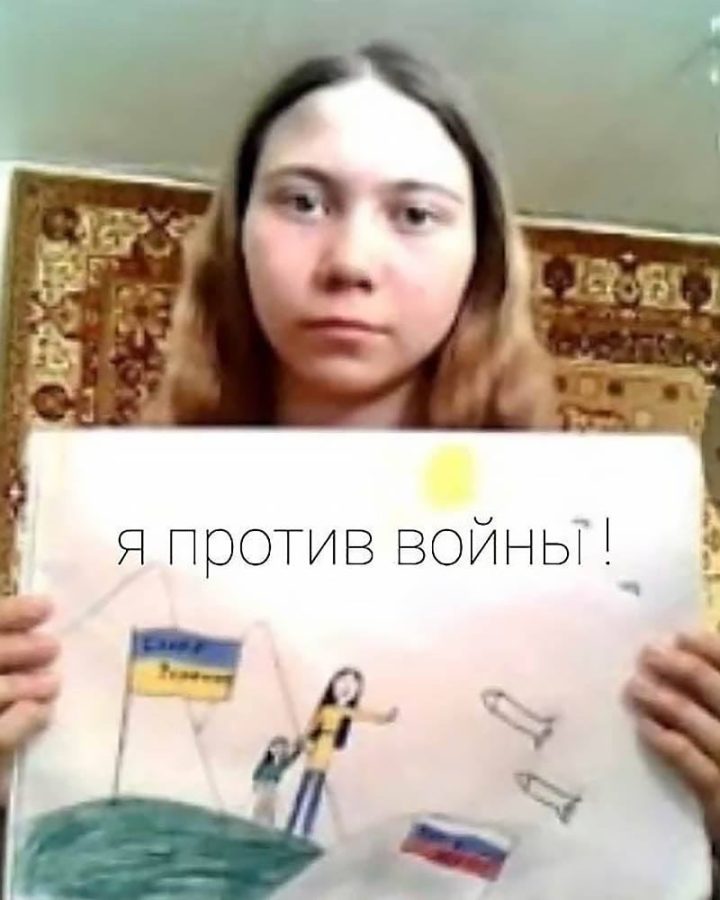

In Russia, nowhere – and no one – is safe from the insidious reach of Putin’s war in Ukraine. In April 2022, during a school art class, twelve-year-old Masha Moskaleva drew a picture of a Russian and Ukrainian flag with missiles flying at a mother and child. Inside the flags, she had written ‘Glory to Ukraine’ and ‘No to War’.

Masha’s art teacher saw her drawing and called in the head teacher who then called the police. Officers interrogated her and her classmates, but Masha managed to slip away after giving them a false name. The following day, as her father, Alexei, was picking her up from school, the two were apprehended by police and taken for questioning.

Тhis shows how the state’s propaganda machine is working its way into the country’s schools

During his interrogation, Alexei was accused of ‘discrediting the army’ over posts on social media which he denies writing. He was charged, fined 32,000 RUB (£340) and a criminal case was opened against him. Masha, meanwhile, was interrogated by the FSB and, traumatised by the incident, refused to go back to school.

Fast forward to 30 December and Masha and her single father were woken up by an FSB raid on their home. The security services ransacked the house, took Alexei into custody and forcefully removed Masha to an orphanage. Alexei was accused of neglecting his parental duties towards his daughter, and even though both were briefly reunited, since the beginning of March the two have not been allowed any contact.

On Tuesday, Alexei Moskalev was sentenced to two years in prison for repeatedly ‘discrediting’ the Russian army. However, his legal team disputes the conviction, arguing, almost certainly correctly, that it is a concocted screen to punish him for the actions of his daughter. Moskalev was, it turns out, sentenced in absentia, after it was revealed (following the verdict) that he had actually fled house arrest on 27 March. After several days on the run, Moskalev was reportedly captured and detained in Minsk, Belarus, in the early hours of 30 March.

Masha’s whereabouts are currently also unknown, after the orphanage the authorities claim she is being housed in have reportedly told supporters of the pair that she is currently not there. A petition calling for Masha to be returned to her father has, so far, gained nearly 145,000 signatures. Meanwhile, a trial aimed at depriving Alexei of custody of Masha is due to be heard on 6 April.

The fate that has befallen this father and daughter over the past year or so demonstrates just how Kafka-esque Russia has now become. In what free country would a teacher call the police, or the security services interrogate a twelve-year-old girl, over a drawing? Paranoia and jingoism has seemingly spread through all elements of society – as the Kremlin hoped it might.

Masha is not the only child in Russia for whom school has ceased to become a safe space from the war. Stories are beginning to appear on Russian social media and in the independent press of Russian teachers doling out excessively harsh discipline or, as in Masha’s case, calling the police over insignificant or minor misdemeanours.

One video doing the rounds on social media at the beginning of the month shows a boy, said to be around fifteen years old, being told off by his teacher for being late to school. The day in question is 23 February, celebrated in Russia as ‘Defender of the Fatherland Day’, appropriated by the state this year, unsurprisingly, as a celebration of all those fighting in Ukraine.

The teacher’s reaction to her pupil’s tardiness is shocking in its harshness: she calls the boy a ‘traitor’ for being late, she kicks him out of her class, says she’s already called his mother. He’s a ‘bastard’ and ‘nothing to her’; traitors like him get it ‘right here in the temple’, she says, prodding him in the side of the head.

Some of these incidents, can of course, be put down to jobsworthy teachers. Others could, reasonably, be accounted for by teachers terrified that they might be held responsible for the actions of their pupils; better to report them than face consequences themselves. If so, this shows how the state’s propaganda machine is working its way into the country’s schools.

Over the last month, new desks have been rolled out in Russia’s schools. Wrapped in green, the desks bear photographs of soldiers killed in Ukraine along with their biographies. Championed by the ‘United Russia’ party, these macabre work stations have been branded ‘Heroes’ desks’ – only those children who come top of the class will be afforded the ‘honour’ of sitting at them. At the unveiling of one such desk at a school in Irkutsk, two children fainted, reportedly ‘affected’ by the tears of the dead soldiers’ relatives who attended the ceremony.

Masha Moskaleva will, no doubt, not be the last Russian child to fall victim to teachers more concerned with upholding state propaganda than safeguarding their students. As the Kremlin knows only too well, the most effective way to uphold an oppressive regime is to manipulate the minds of the next generation: to that end, teachers are their most effective weapon.

Comments